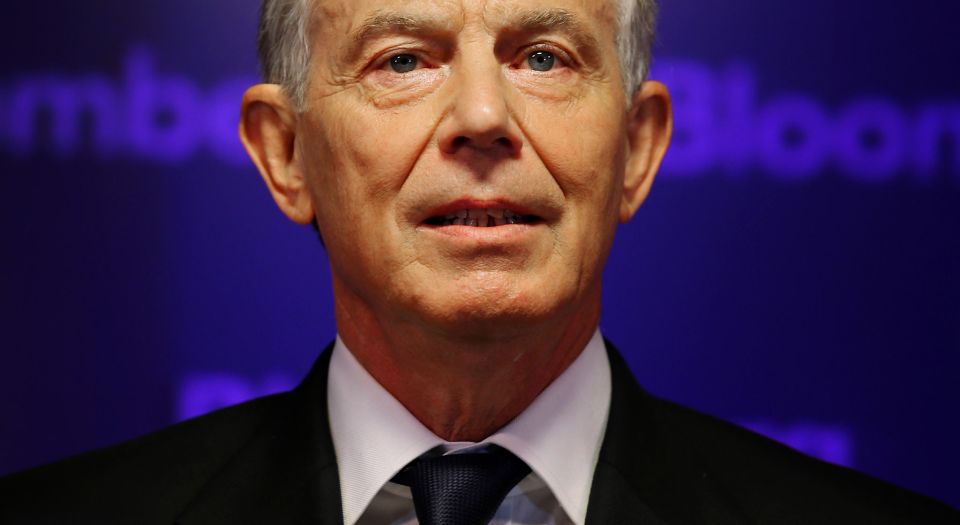

The crucifixion of Tony Blair

Chilcot allows politicians to blame Blair for their own failings.

Want to read spiked ad-free? Become a spiked supporter.

What exactly is the point of the Chilcot report? We know the ostensible reason, of course. Its self-stated aim is to investigate ‘the run-up to the Iraq War and its aftermath’, in order ‘to establish, as accurately as possible, what happened and to identify the lessons that can be learned’. And we know that its scope is ‘unprecedented’, its purpose ‘essential’, because that’s what the then prime minister, Gordon Brown, told us when he launched the inquiry, over seven years ago. But does that really explain the political and media classes’ excitement ahead of its publication?

After all, it’s not as if it can tell anybody anything substantial they don’t already know, least of all politicians, many of whom had ringside seats in 2003 as Tony Blair’s New Labour government eagerly sent British troops ‘over the top’. The evidence for weapons of mass destruction was always non-existent; the claim Saddam Hussein could launch chemical weapons within 45 minutes always dubious; Blair’s and New Labour’s belief in ethical foreign policy always overriding. No doubt nestling among its 2.6million words, there will be hitherto unknown details revealed, exchanges between Bush and Blair unveiled, expert warnings ignored. But nothing that will transform our understanding of what happened, nothing that will cause the scales to fall from our eyes.

And why would it? The politically subconscious point of the Chilcot report, the reason why it has been fetishised, lies not in the tedious 12 volumes themselves, but in a massive act of political-class projection — a projection of their political and moral failure to oppose the invasion of Iraq on to the figure of Tony Blair specifically, and New Labour generally. The Chilcot report promises nothing less than absolution for this political class. In its attribution of blame and responsibility, in its identification of official errors and decision-making flaws, it promises to exculpate the political class, to absolve it of responsibility for failing to make the case against the war, for failing to recognise, as spiked did 13 years ago, that appealing to the UN for a legal sanction to invade Iraq was not actually an objection to intervention on principle. In Chilcot, a political establishment, in which an overwhelming majority of MPs voted in favour of invading Iraq in 2003, sees its redemption.

You can hear the desperation in the political commentaries. ‘This is why the Chilcot Inquiry matters a great deal’, writes one: ‘It is the last chance for the British Establishment to show it can learn the lessons of its failures — and hold those who fail to account.’ Another argues that the Chilcot report can ‘restore trust in the process of decision-making in government’. And another concludes that Chilcot provides a way ‘to drain the poison that has built up in our national life since Blair took the calamitous decision to follow the US into invading a country that its president knew zip about’.

In fact, the fetishisation of the Chilcot report is not really about the invasion of Iraq at all. It’s about ‘restoring trust’, ‘learning the lessons’, ‘draining the poison in national life’. It’s not driven by the dawning awareness of the barbarism of overseas interventions. No, it’s driven by the political class’s sense of its own illegitimacy, its distance from those it governs, its internally corrosive lack of democratic support. It projects this crisis on to Blair and New Labour, and blames them for it, drawing attention to their famed obsession with spin and soundbites, their love of a politics of style over substance. It all culminates in the sexed-up, dodgy-dossiered rationale for invading Iraq. This is why the Chilcot report appears as a magical restorative, a medicine that will purge the body politic of its corrupting elements.

For Labour, this self-obsessed use of the Iraq War to try to purge and reinvent itself, is intensified. As a Sky News interviewer said to Blair this weekend, ‘there must be times when you wonder and the people wonder why do members of the party, that you devoted your sole political life to, hate you so fundamentally?’. Blair struggled to respond, but the answer is clear enough. Blair, in his New Labour pomp, is seen as the root of all Labour’s current troubles, the source of its loss of identity and purpose.

Blair, you see, supposedly emptied Labour of its old Labour traditions, and, in doing so, evacuated it of traditional supporters. That Labour was hollowed out long before Blair took over, as it struggled to readjust its role following the collapse of the postwar settlement, is determinedly ignored. For Labour today, it’s all about Blair. He’s the problem, and the Iraq War his crowning infamy. Hence all the excited talk about Labour leader Jeremy Corbyn clinging on to his position in order to call for Blair’s impeachment come Chilcot Day, or the enthusiasm among Labourites for figuratively ‘crucifying’ Blair, as ‘a war criminal’. Like the political class as whole, Labour wants to use the Chilcot report to cleanse itself.

Above all, this vain obsession with Chilcot speaks to the depoliticisation of the political class. The Iraq War here is not being grasped as a political and moral failure; it’s being eagerly portrayed as the error of a set of individuals, a product of their scheming and delusion. The solution thus appears technocratic: if only the decision-making process was better managed, with more checks, more balances and more experts, then none of this would have happened. It all makes for a dispiriting spectacle. The absence of political and moral judgement so palpable over a decade ago, as legal cretins spoke of UN resolutions and warmongers of ‘doing the right thing’, is still all too apparent today. The crucifixion of Tony Blair might make politicians feel better, but, for the rest of us, it’s a pointless distraction.

Tim Black is a spiked columnist and editor of the spiked review.

Who funds spiked? You do

We are funded by you. And in this era of cancel culture and advertiser boycotts, we rely on your donations more than ever. Seventy per cent of our revenue comes from our readers’ donations – the vast majority giving just £5 per month. If you make a regular donation – of £5 a month or £50 a year – you can become a and enjoy:

–Ad-free reading

–Exclusive events

–Access to our comments section

It’s the best way to keep spiked going – and growing. Thank you!

Comments

Want to join the conversation?

Only spiked supporters and patrons, who donate regularly to us, can comment on our articles.