Long-read

Shakespeare at work

What history can and can’t tell us about Shakespeare’s continued resonance.

Want to read spiked ad-free? Become a spiked supporter.

With 1599: A Year in the Life of William Shakespeare, James Shapiro, a professor at Columbia University in New York, produced a magisterial book on Shakespeare born of microscopic attention to detail. Out of what was to become Shapiro’s trademark swirl of historical and textual detail, from the time of a sunset on late December day in 1598 to the fading of Chivalric culture – all set against the unfolding ‘Irish problem’ – an image of Shakespeare emerged, a man who might be for all time, as Ben Jonson put it, but who was also very much of his time. To those who want their Shakespeare transcendent and timeless in his genius, 1599 was a compelling riposte. Shapiro followed this up in 2010 with Contested Will: Who Wrote Shakespeare?, his unvexed response to the vexed question of Shakespeare’s authorship (the answer: Shakespeare). And last year, he turned his forensic mind to another year in Shakespeare’s life – 1606: William Shakespeare and the Year of Lear – conjuring up the specificity of the Jacobean Shakespeare’s cultural and political universe in all its exotic richness.

But Shapiro’s work raises questions, too: What exactly do we know about Shakespeare? Can his work be characterised as universal? And is there a danger of over-historicising Shakespeare, of reducing his work to its precise historical moment? We decided to put these questions and more to Shapiro.

spiked review: In Contested Will: Who Wrote Shakespeare?, you convincingly debunk the often fantastical theories about who was the ‘real’ author of Shakespeare’s plays, be it Francis Bacon or Edward de Vere, Earl of Oxford. But, although we can be certain that Shakespeare wrote these plays, why do we know so little about this glover’s son from Stratford? Why do we seem to know far more about some of Shakespeare’s contemporaries, like Christopher Marlowe or Ben Jonson?

James Shapiro: That’s a question that puzzles many 21st-century readers. The easy answer is that both Marlowe and Jonson are outliers. That is to say, Marlowe worked for the government, had a record at Cambridge that was preserved, and he was killed, which led to an inquiry, and, in turn, led to records being kept. Jonson lived a very long life, found himself in prison, wrote many letters to patrons that have been preserved, and was obsessed with publication. For those reasons we know more about Jonson and Malowe. But the kinds of things we want to know about Shakespeare, we don’t know about Marlowe and Jonson either. Who were Marlowe’s friends? We don’t know. Who did Marlowe and Jonson sleep with? Who did they love? We don’t know. What were their relationships with family members? We don’t know. So of the dozens of playwrights who wrote for the stage during the reigns of Elizabeth I and King James, we know more about Shakespeare than we do perhaps any other, with the exception of Marlowe and Jonson. I’d love for you to tell me about Thomas Kyd or John Webster or others. It’s unclear when and where many were born and when and where they died.

If we look at it from a 21st-century perspective, it is as if the only information that was kept about me was motor-vehicle records, records of birth, marriage and death, and reports of hospitalisations – there wouldn’t be much of my life in that lot. There would just be the bare bones of it. And that’s what we have for Shakespeare. Ironically, there’s a lot more for him than for the vast majority of those who write for the stage today.

review: How were playwrights viewed in Shakespeare’s time? Were they esteemed, seen as uniquely insightful individuals, in the way they are now?

Shapiro: I should say that I don’t think playwrights are particularly esteemed today. If you were to walk down the street and ask people to name five or six contemporary playwrights, I’m not sure many could. In the 16th century, the profession of playwright went from one that was associated with vagabonds to one that was associated with authorship, literary esteem, laureateship, proximity to the throne and proximity to the court. So Shakespeare lived through a period when the prestige of writing rose considerably.

review: So playwrights were not seen as uniquely creative individuals, as potential geniuses, as the Romantics had it?

Shapiro: Nobody went around calling Shakespeare a genius in his own day. Nobody went around saying ‘Ah, 400 years from now they’ll be celebrating his death or birth’. I think we have let a nostalgic patina settle over these writers, and if you scrape away at that, you would see people like Shakespeare, getting up in the morning ready to rehearse the day’s play, putting on that play in the afternoon and writing late into the night – perhaps working 12-, 13-, or 14-hour days. Shakespeare wasn’t celebrated. His name doesn’t appear on a title page until 1598. And, certainly, he worked exceedingly hard, but he wasn’t recognised in terms of a genius in his own age. No one was.

review: If there is one abiding image of Shakespeare that comes through in your work, it’s that of a craftsman, his dedication to writing, his gutting and renovating of existing texts. Is that a fair image?

Shapiro: I think it is. If Tom Stoppard can write Shakespeare in Love, a working title for the books I’ve written would be Shakespeare at Work. We know that the things we want to know about Shakespeare’s personal life – what his religious beliefs were, what his political beliefs were, the kind of people he loved or spent time with – is all lost to us. But what’s not lost to us, thanks to surviving records, is what Shakespeare did professionally, what the products of that work were, and, to a remarkable extent, his working methods, what he read, how he transformed what he read, the kinds of stories or sources he was excited by, where he entered those stories, and what he did to transform them, renovating them. Originality didn’t count for much in his day; telling a great story did. So whether it’s Hamlet or King Lear, Shakespeare’s not making stories up. He’s not even making a story up as a stage play – his two greatest plays are rewrites of earlier plays.

review: You mention King Lear there, which of course is the focal point of your most recent book, 1606: William Shakespeare and the Year of Lear. And you make the point that Shakespeare’s later plays, like Lear and Macbeth, are linguistically far denser, far knottier. Why do you think that is? Is it because, following his retirement from acting, he was more deeply immersed than ever in the craft of writing?

Shapiro: It’s funny, I’d been warned away from the new Macbeth film, but I saw it the other day with my wife, and we were just rapt, listening to very talented actors recite the lines of this play. I don’t know how many were cut – they have to be for a film – but it was mesmerising. The language was just extraordinary. And I think that late Shakespeare, when he’s spending less time in the theatre and more time writing and collaborating, is producing linguistically remarkable, not to mention hard, plays – and here I’m deeply indebted to Frank Kermode’s Shakespeare’s Language, where he talks about the knotty, difficult, and sometimes even incomprehensible Jacobean poetry Shakespeare was producing at that stage.

One of the great challenges I have working with professional theatre companies – for instance, I work trimming texts that are taken to prisons and other institutions that don’t allow for more than a 90-minute production of a Shakespeare play – involves the later plays. A play like Romeo and Juliet (written in the early 1590s), is actually quite easy to cut to length. But even though Macbeth is a much shorter play, it’s impossible to cut. You realise that these later works are lean, mean plays, and you do harm when you start wielding the knife on them.

review: One of your most compelling assertions, given talk of making Shakespeare relevant and so on, is that Shakespeare is resolutely not our contemporary. But is there still something universal to his works?

Shapiro: I wouldn’t use the term universal. I would say that Shakespeare’s plays continue to speak to us, 400 years or more after they were written, because we live in an age that is still struggling to work out the issues that his age, probably for the first time, was struggling to resolve. Questions of: what is a nation state?; what does it mean to profess a religion that is different to the religion of our grandparents?; what do we do with different notions of nationality, and ethnic and sexual difference? And the reason why the plays still speak to us from that distance is that you open the newspaper today and you read about people struggling with their gender identity, or nationalism on the rise, or ethnic struggles, or theological struggles, all of which bears a striking resemblance to issues addressed in Shakespeare.

But I never use the word universal because it implies that in each country Shakespeare might mean the same thing. When I go to see Shakespeare in Israel or Japan or Germany or Ireland, it’s a very different Shakespeare to the one I see in London or Stratford-upon-Avon, and that, in turn, is a quite different Shakespeare to the one I see in my native New York.

review: Can you give an example of the type of difference you mean?

spiked: Sure. When Garry Hynes stages the history plays for the Irish Druid Theatre Company, one finds oneself looking at those plays in terms of a nine-year-long war to crush an Irish rebellion. But when Greg Doran puts them on for the Royal Shakespeare Company, he looks at the state of England and Great Britain today. Each one of us reads Shakespeare, but we do so in ways that speak to us, and that don’t speak to others. If that’s not an example of how Shakespeare’s not universal, I don’t know what is.

review: You write, quoting Hamlet, that Shakespeare gives ‘the very age and body of the time his form and pressure’. How does he do this?

Shapiro: He lived in an age in which there were no other real, competing media, other than Royal proclamations and public sermons. The theatre was the place where political views were expressed and contested – not just political views, but economic views, social views. It’s all there. As You Like It is a frothy Romantic comedy, but it’s also a story about two ways of looking at the English landscape, the old oak trees and forested world that was stripped away in Medieval England, and the much more contested world in which shepherds are working for landlords and those landlords dismiss them, and send them on the road to starve or die. So scrape down a little deeper and I’d say Shakespeare’s gift is that he’s writing plays that work for us in the way that marriage-plot novels work, in which there’s a deeply satisfying movement towards closure and things that make audiences happy – marriage in particular – and plays, again like As You Like It, in which a boy actor plays a girl, and dresses as a boy, to seduce a man to marry her. These are plays that speak pretty directly to us about issues that resonate today.

So, I’d say Shakespeare’s plays are successful in the sense of being powerful tragedies and comedies, which pack an emotional punch, and yet, within each one of those plays, there’s a tremendous amount going on to study, to engage, to perform that’s meaningful, and that can begin to illuminate our cultural values, then and now.

review: But what is it about that late Elizabethan, Jacobean moment, to which Shakespeare is giving his ‘form and pressure’, that proves so artistically fertile?

Shapiro: Why does tragedy only occur in rare moments like Ancient Greece or Rome or Renaissance Europe or 20th-century Europe and America? Those are the mysteries: the lining up of the stars, the constellation of social and political freedoms and pressures that produce moments – historical moments – where not just one or two, but any number of talented writers are writing in certain kinds of forms. That’s a mystery that, despite my 30 years spent teaching, I can’t begin to answer. You certainly need a critical mass of talent, and Shakepeare’s period had that – there was an enormous amount of talent. And there were other factors, too: the changing education systems; the plate tectonics of post-Reformation change… I could come up with 20 explanations, but that doesn’t explain the mystery of ‘why?’.

review: You mention the ‘plate tectonics of post-Reformation change’ – does the burgeoning sense of selfhood play a role in making that late-Elizabethan, Jacobean moment so exceptional?

Shapiro: Absolutely. That’s part of it. There’s also a massacre of Protestants in Paris, and refugee crises and so on – I don’t want to put a blandly positive spin on the Reformation. There was blood on the street and a lot of extraordinary political and literary writing that emerged out of that fraught moment.

review: Why did you focus on 1599 and 1606 in particular?

Shapiro: First, 1599 was an easy choice. It was the year Shakespeare’s Globe rose. There’s always been a division among Shakespeare scholars about whether to see Shakespeare as a poet or as a man of the theatre, and I see him as someone deeply shaped by the theatre, by the playing company in which he acted, so choosing 1599 was a way of throwing down the gauntlet in that argument, and making the case for Shakespeare as a playwright, an actor, before he was a writer obsessed with authorship and publication.

Now, 1606 was in many ways an act of penance for ignoring the last creative decade of Shakespeare’s life, and speaking of him in a rather reductive way as an Elizabethan playwright. He was also a Jacobean playwright and the Jacobean Shakespeare was not working under the same conditions and pressures as the Elizabethan one, and I thought I had best learn a little more about the Jacobean Shakespeare. I could have chosen 1603 or 1611 as easily as I chose 1606, but I chose 1606. And once you choose, you’re stuck – the advances are paid and the research is beginning!

review: Both 1599 and 1606 have an incredibly historicising focus, embedding Shakespeare’s work in a particular literary and historical context, showing how he drew from and repurposed extant literary sources, and drawing attention to the events that would have preoccupied the minds of the theatre-going public. So to what extent is this approach to be associated with New Historicism, that mode of literary criticism, which, as Jonathan Bate put it, views literary creations as cultural formations shaped by ‘the circulation of social energy’?

Shapiro: I grew up in the age of New Historicism, but I wasn’t a regular churchgoer. I’d go to Shakespeare Association of America meetings, and read the work of David Kastan and Stephen Greenblatt and other really extraordinary New Historicists. They were people I admired and read very carefully. But I was not of their generation. They were creatures of the 1960s, and I grew up a decade later – I was born in 1955. So I came at things from a slightly more oblique angle than they did. I was left a bit dissatisfied by the thinness of New Historicism, which, in its most caricatured form, would rely on finding a single anecdote – for instance, Queen Elizabeth supposedly saying ‘I am Richard II, know ye not that?’ – and then writing up an elegant conference paper about what that might have meant. I felt I needed what anthropologists call a ‘thicker’ description. And, I thought, if I’m going to do that, I might as well read everything written in the particular timeframe of a year – which is an arbitrary timeframe, but still a good place to start. So, my work emerged out of my debt to, and my frustration with, New Historicism.

review: What do you make of the principal charge levelled against New Historicism, namely, that it reduces works to their historical context?

Shapiro: Yes, I recognised that problem with New Historicism pretty early on, and I think its greatest practitioners saw that problem pretty early on, too, but were trapped by the success of their methodology. I think a better way of putting my own perspective is that we can’t make sense of the cultural moment without the benefit of writers like Shakespeare. And we can’t make sense of Shakespeare without the benefit of understanding the extent to which he is immersed in, and responding to, his historical moment.

So, to push it a little further, I think what I cared about more than most New Historicist critics was the unusual role of theatre in shaping public discourse and public conversation. And once you believe in that you can start seeing the ways in which you can know what people were thinking and what people cared about – the economy, the weather, military conscription, succession – on their way to the theatre, what brings them to the theatre, and then you have to realise this is a commercial enterprise, and if writers are not writing about things that people care deeply about, then those playgoers will go across the road to, say, the Rose Theatre, or, in the northern suburbs, the Fortune, the Red Bull, or anywhere else in London. So this competition is putting enormous pressure on these playwrights to speak to the moment, without overstepping the bounds of what is acceptable and putting themselves in harm’s way, or potentially in prison.

review: What do you think of the reaction against what is seen as the relativism of the historicising approach, New Historicist or otherwise? The sense that the focus on the context somehow deprives works of their purely literary, artistic value? I’m thinking here, for instance, of Harold Bloom’s 1998 book on Shakespeare.

Shapiro: Bloom is one of the great, great readers and literary critics of our day, and he’s also somebody who deeply believes, as I don’t, that Shakespeare created what he calls ‘the human’. Bloom is also on record as saying he hasn’t gone to a play in a half-century, so he aligns himself with a long tradition, a Romantic tradition, that reads Shakespeare as this genius, struggling away in some attic and working in isolation. But Bloom was never a cultural historian of the early modern period, and he was never interested in what was actually going on in the theatre.

I suppose – and I’m just thinking out of the box for a moment – when we go to a restaurant, and somebody serves up an extraordinary dish, and we eat it and enjoy it and we say, ‘wow, that was inspired’, you know what; it probably was inspired. But if you go back, go into the kitchen, and see the fights and the screaming, see what kind of knives are being used, what sauces are being created, and then you go back to the markets where those goods are sourced and sold, and then you go back to the farms where somebody grew those vegetables with love, you’re getting a very different perspective on what ended up on your plate. I think Bloom’s more interested in what ended up on your plate, and I’m as interested in how it got there.

review: How do you account for Shakespeare’s centrality to the English canon? Given it’s also the 400th anniversary of Cervantes’s death, does his work play a similar role in a Spanish literary tradition?

Shapiro: I’m going to have to go and argue with a Cervantes scholar next month about who’s had the greater impact, whose cultural footprint is bigger – Shakespeare or Cervantes. The English-speaking world versus the Spanish-speaking world. It’s a really complicated question, and there have been scholars who have written a great deal about the reasons and conditions for the way Shakespeare emerged in the late 17th and early 18th century as a national poet, when England was struggling to define, and redefine, itself in a lot of different ways. I can answer the question of how Shakespeare became a national poet more easily than I could answer why he remains the national poet two centuries after his emergence as England’s star – that is a question, we, as scholars, haven’t wrestled with enough. It’s not as if he was a rocket ship that was launched 200 years ago and it is now in orbit. Reputations normally go up and down. Is Pinter’s stock up or down? Is Stoppard’s stock up or down? But Shakespeare’s stock is remarkably consistent. Even the plays that we love are consistently beloved. It’s not as if one age loves Hamlet, King Lear and Macbeth and the next one prefers Love’s Labour’s Lost, King John and Henry VIII. The plays we love, we love and audiences flock to. Anyone who runs a theatre can tell you how tough it is to fill seats for the least popular of Shakespeare’s plays. So it’s the consistency of his ability to thrill audiences four centuries later that’s the real mystery of Shakespeare.

review: So, finally, do you have a favourite Shakespeare play?

Shapiro: I do, and it’s whatever I’m working on at the moment! I’m incredibly disloyal and fickle. I’m working on a production with the Public Theater in New York right now on Romeo and Juliet, and it’s my absolute favourite. A play that I never teach, The Taming of the Shrew, is going to be done at the Public this summer, with Phyllida Lloyd directing, and I’m sure if you asked me this question a few weeks from now, Shrew would be my absolute favourite. It’s the immersion that’s key. I spend a lot more time in rehearsal rooms now, and you get a very different feel for a play there than you get in the academic study of a play in a library. It’s hard not to fall in love with a play that you’re working on.

James Shapiro is professor of English and comparative literature at Columbia University. He is the author of many books, including: 1599: A Year in the Life of William Shakespeare (2006); and, most recently, 1606: Shakespeare and the Year of Lear (2016).

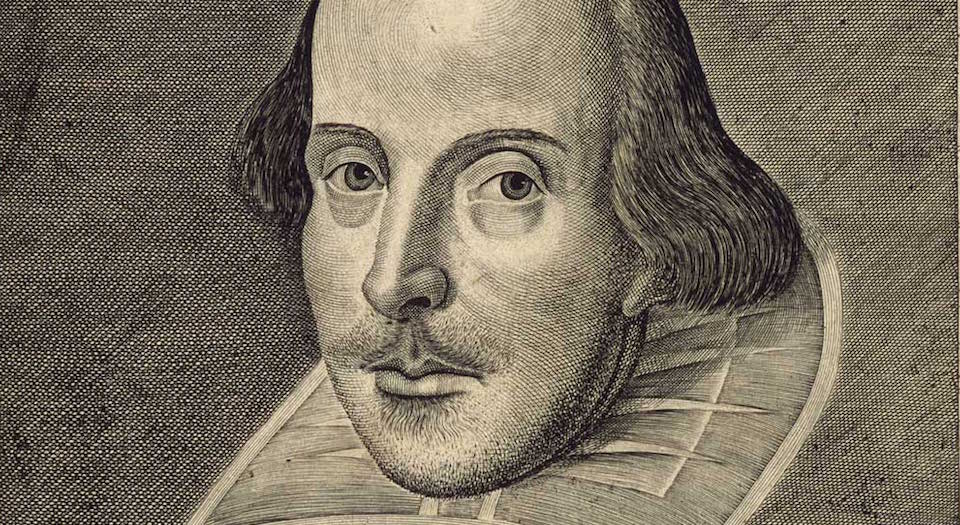

Picture: Mr. William Shakespeare’s Comedies, Histories, & Tragedie (1623).

Who funds spiked? You do

We are funded by you. And in this era of cancel culture and advertiser boycotts, we rely on your donations more than ever. Seventy per cent of our revenue comes from our readers’ donations – the vast majority giving just £5 per month. If you make a regular donation – of £5 a month or £50 a year – you can become a and enjoy:

–Ad-free reading

–Exclusive events

–Access to our comments section

It’s the best way to keep spiked going – and growing. Thank you!

Comments

Want to join the conversation?

Only spiked supporters and patrons, who donate regularly to us, can comment on our articles.