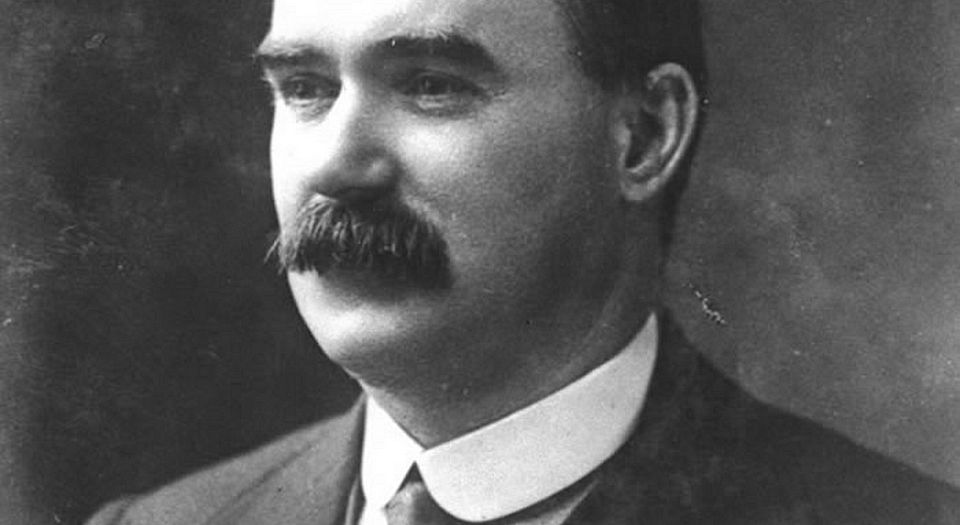

James Connolly: we only want the Earth

What we can learn from the hero of the Easter Rising.

Want to read spiked ad-free? Become a spiked supporter.

‘God’s curse on you England, you cruel-hearted monster

Your deeds they would shame all the devils in Hell

There are no flowers blooming but the shamrock is growing

On the grave of James Connolly, the Irish Rebel.’

So goes the Wolfe Tones’ 1967 hit about the death of a ‘true son of Ireland’, James Connolly. But Connolly, the hero of the Easter Rising, has been largely misrepresented. This is hardly surprising. Those unwilling to celebrate the ambition of the Easter Rising are similarly uncomfortable with recognising its most important figure. And Connolly was its most important figure. He was one of the few men in Irish history who was right about what it took to defeat British rule and revolutionise Ireland. Ireland’s only hope for independence in any meaningful sense died with Connolly on 12 May 1916.

Born in Edinburgh in 1868, Connolly left school at 11 and joined the British Army at 14 (using a false name). After seven years he discharged himself and returned to Scotland where his interest in socialist politics grew. He taught himself enough French and German to read the works of Marx and Engels.

While still in his twenties, Connolly, now a married man with two children, was involved in the Independent Labour Party (the forerunner to the Labour Party), and he also pursued trade-union politics among several groups such as the Scottish Socialist Federation. In 1895, he moved to Dublin to take up the role of secretary to the Irish Socialist Republican Party, before moving to America in 1903, where he was a member of the Socialist Labor Party of America, the Socialist Party of America and the Industrial Workers of the World.

What set Connolly apart from many of his comrades, many of whom were immersed in trade-union politics, was his revolutionary perspective. His trade-unionist peers were happy with piecemeal reforms, but that was not enough for Connolly. As he put it in 1910: ‘The day has passed for patching up the capitalist system; it must go.’

This revolutionary impulse is precisely what drove Connolly to ally himself with James Larkin and the Irish Labour Party in 1910. The Dublin Lockout in 1913, when approximately 20,000 workers were engaged in the most significant industrial dispute in Irish history, confirmed Connolly’s move away from trade unionism. In a scathing condemnation of the English Labour Party, which failed to come out in support of the Lockout, Connolly wrote: ‘We will be troubled no more by carping critics of Labour politics, nor yet with Labour politicians.’ Labour’s complicity with the powers-that-be is a lesson many on the left have still to learn.

Following the violence and brutality of British troops during and after the Lockout, Connolly set up the Irish Citizens Army (ICA) to protect the working classes’ right to assembly and free association. It was with the ICA that he outlined his determination to forge a revolutionary working-class movement. As he reflected in 1915:

‘An armed organisation of the Irish working class is a phenomenon in Ireland. Hitherto the workers of Ireland have fought as parts of the armies led by their masters, never as members of an army officered, trained, and inspired by men of their own class. Now, with arms in their hands, they propose to steer their own course, to carve their own future.’

1914 was a turning point for Connolly. The failure of the Dublin Lockout was a huge blow to the Irish working class, but there was growing tension elsewhere. The Irish Parliamentary Party had split after its leader John Redmond decided that Irish men should join up with British troops in the war with Germany in return for British support for Home Rule. At the same time, petit bourgeois nationalists like Pádraic Pearse were joining the Irish Republican Brotherhood with the hopes of fighting, not for Home Rule, but for Irish independence.

Redmond’s selling-out of the national struggle gave Connolly the opportunity to reinvigorate the battered Irish working class. In a 1914 article, ‘War – what it means’, he rubbished Redmond’s idea that fighting for England would give Ireland a better chance at freedom: ‘Will the anti-Irish aristocrats who are rushing in to become your officers allow you to take a stand for Irish nationality?’ But Connolly’s call was not only to the Irish working class, but to the working class in every nation. ‘Let the Empire go its own way’, he wrote, and ‘let those who own it fight its battles. It is not yours, you are but its slaves, and surely there is nothing in creation meaner than slaves fighting for the source and basis of their enslavement.’

Connolly recognised that it was now or never for a successful working-class rebellion in Ireland. Long after the Easter Rising’s defeat, critics on the right claimed that it was just a nationalist enterprise, while many on the left claimed that the nationalist struggle prevented Connolly from following a programme of day-to-day small changes to improve the condition of the working class. But the reason Connolly was right to seize the moment as he did was that he understood that neither a class struggle nor a nationalist movement could succeed in isolation.

Connolly argued that while the Irish were under British rule, the Irish working class could never win a struggle for freedom. He also understood that, without a socialist politics with the interests of the working class at its heart, the nationalist movement would only serve to put an Irish elite in charge. The most poignant scene in Ken Loach’s film, The Wind that Shakes the Barley, is set in jail in the aftermath of 1916, with Dan and fellow fenian Damien recalling Connolly’s famous 1897 piece, ‘Socialism and Nationalism’, in which Connolly writes:

‘If you remove the English army tomorrow and hoist the green flag over Dublin Castle, unless you set about the organisation of the Socialist Republic your efforts would be in vain. England would still rule you. She would rule you through her capitalists, through her landlords, through her financiers, through the whole array of commercial and individualist institutions she has planted in this country and watered with the tears of our mothers and the blood of our martyrs. England would still rule you to your ruin, even while your lips offered hypocritical homage at the shrine of that freedom whose cause you had betrayed. Nationalism without Socialism – without a reorganisation of society on the basis of a broader and more developed form of that common property which underlay the social structure of Ancient Erin – is only national recreancy.’

Many underestimate the gravity and scope of Connolly’s vision. He was not prepared to stop at the Easter Rising: he knew that, following a nationalist victory, the next battle would be between the Irish workers and their own ruling class. On Palm Sunday, a week before the rising, Connolly warned the ICA: ‘In the event of victory, hold on to your rifles, as those with whom we are fighting may stop before our goal is reached. We are out for economic as well as political liberty. Hold on to your rifles.’ The scope and aims of 1916 are embodied in Connolly — not only did he want self-determination for Ireland, he also wanted radically to transform the way Ireland was run. Connolly understood that the success of the rising would only be the start of a much bigger battle, one he hoped would inspire workers around the world also to rise up.

Due to the betrayal of nationalists within the movement, and the strength of the British Army, the rising failed. Following his capture, Connolly was due to be executed at dawn on 12 May. Having been seriously injured during battle, he was first placed in a chair by his executioners, but it toppled over twice. They eventually had to strap him to a stretcher before they could shoot him dead. The execution took place in a separate part of Kilmainham Jail to that of the other rebels, because it had a higher wall — they did not want the shots to be heard by the public. Ireland’s British rulers then buried Connolly in haste in an attempt to deny him martyr status, and to hide the brutality of his execution.

With Connolly gone, so the possibility of a working-class revolution and a free Ireland started to wither. None of his nationalist successors were interested in a free Ireland if it meant a socialist Ireland.

A verse from one of Connolly’s ‘Songs of Freedom’ (1907) still resonates:

‘“Be moderate,” the trimmers cry,

Who dread the tyrants’ thunder.

“You ask too much and people fly

From you aghast in wonder.”

’Tis passing strange, for I declare

Such statements give me mirth,

For our demands most moderate are,

We only want the Earth.’

The final refrain is chilling. Above all else, the centenary of the Easter Rising should remind us that Connolly was a man for whom the sky was the limit. His was a vision of Irish people’s freedom, not just from imperialism, but from capitalist exploitation, too. He might not have been the greatest theoretician, but he was right about Ireland. Lenin recognised as much when he said to those who denounced the Easter Rising: ‘Whoever calls such an uprising a “putsch” is either a hardened reactionary, or a doctrinaire hopelessly incapable of picturing a social revolution as a living thing.’ Connolly, like Lenin, understood, following Marx, that ‘men make their own history, but they do not make it as they please; they do not make it under self-selected circumstances, but under circumstances existing already, given and transmitted from the past’.

How do you remember a man whose political scope and desire for change was so great? In whatever embarrassed and muted form the Irish state decides to celebrate the centenary of its origins, one thing is for sure: Connolly, and what he really stood for, won’t be part of it. Working-class politics in Ireland is as dead as the nationalist movement with which it was once entwined.

Connolly would not have been surprised by its demise. He warned that to partition Ireland would provoke a ‘carnival of reaction both North and South. It would set back the wheels of progress, destroy the oncoming unity of the Irish labour movement and paralyse all advanced movements whilst it endured.’ Modern Irish history has vindicated Connolly.

Nor would he have been impressed with the empty slogans and sentiments of the left’s current focus: the politics of hope. So many on the left have forgotten what it is to think big and to stand by their guns. Connolly never compromised. He wanted freedom for Ireland and freedom for the working class across the world. He demanded, not small reforms or hope or ‘respect’, but nothing less than the Earth.

Ella Whelan is staff writer at spiked.

Picture by: the Irish Labour Party, published under a creative commons license.

Who funds spiked? You do

We are funded by you. And in this era of cancel culture and advertiser boycotts, we rely on your donations more than ever. Seventy per cent of our revenue comes from our readers’ donations – the vast majority giving just £5 per month. If you make a regular donation – of £5 a month or £50 a year – you can become a and enjoy:

–Ad-free reading

–Exclusive events

–Access to our comments section

It’s the best way to keep spiked going – and growing. Thank you!

Comments

Want to join the conversation?

Only spiked supporters and patrons, who donate regularly to us, can comment on our articles.