Free speech: the ‘killer app’ of civilisation

It is worth reminding society where we'd be without the liberty to offend.

Want to read spiked ad-free? Become a spiked supporter.

Why do we in the West now spend so much more time discussing the dangers of unfettered free speech and the need to restrict it, than the value of free speech and the need not only to defend but extend it?

A couple of weeks ago at The Times/Sunday Times Cheltenham Literature Festival, I was on the panel for an interesting debate entitled ‘Free speech: no limits?’. The chair, Shami Chakrabarti of Liberty, ensured that most of the hour was spent discussing exactly where and how strict those ‘no’ limits should be.

We have ended up in a situation where everybody in public life can claim to support free speech ‘in principle’, while focusing on ways to restrain it in practice. So in his big speech to the Tory Party conference last week, UK prime minister David Cameron could mention free speech in passing, as one of the key things people in Britain have fought for – then spend far longer arguing that we need less freedom of expression, aka ‘no more passive tolerance’, to tackle the problem of Islamic extremism.

As a society we are in danger of forgetting that free speech is the most important expression in the English language. As I argue in my book, Trigger Warning, ‘sometimes it is necessary to remind ourselves of the obvious and look again at what we take for granted’.

To borrow a phrase from the techies, free speech is the ‘killer app’ of civilisation, the core value on which the success of the whole system depends. It is so all-fired important that every other right or claim should have to get in line behind it.

Freedom of thought and of speech is a key part of what makes us unique as modern humans. Free speech is the link connecting the individual and society. It is the voice of the morally autonomous adult, nobody’s slave or puppet, who is free to make his or her own choices. That is why free speech as we know it could only truly develop in the Enlightenment, when the spirit of the age of modernity was on full volume. It was first captured 350 years ago by the likes of Spinoza, who challenged the political and religious intolerance that dominated the old Europe and set the standard for a new world by declaring that ‘In a free state, every man may think what he likes, and say what he thinks’.

Free speech is about more than individual self-expression. It is the collective tool which humanity uses to develop, debate and decide on the truth of any scientific or cultural issue. Free speech is not just a nice-sounding but impracticable idea, like ‘free love’. It has been instrumental in the advance of humanity from the caves to something approaching civilisation. The open expression of ideas and criticism has proved the catalyst to the blossoming of creativity.

History suggests that the freer speech a society allows, the more likely it is to have a climate where culture and science can flourish. Even before the modern age of Enlightenment, those past cultures that we identify with an early flowering of the arts, science and philosophy, from Ancient Greece to the Islamic Golden Age, had a disposition towards freedom of thought and speech that set them apart.

The advance of free speech has been key to the creation of the freer nations of the modern world. Every movement struggling for more democracy and social change through modern history recognised the importance of public freedom of speech and of the press for articulating their aims and advancing their cause. Hence the demand for freedom of the press and of speech first came to the fore during the English revolution against the tyrannical monarchy in the seventeenth century, and again during the American revolution for independence from the Crown in the eighteenth.

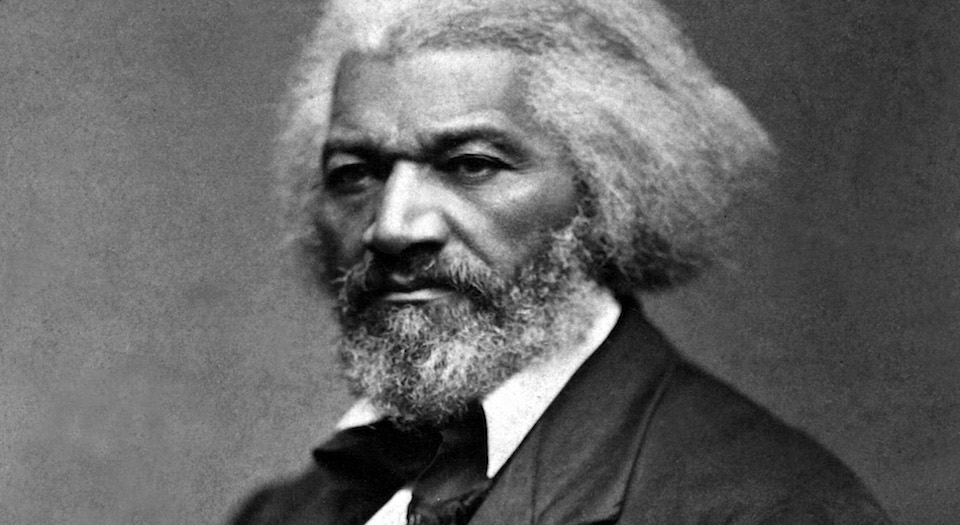

One sure sign of the historic importance of free speech to liberation struggles is the instinctive way that tyrants have understood the need to control it to preserve their power. As the American anti-slavery campaigner (and former slave) Frederick Douglass wrote in ‘A Plea for Free Speech in Boston’, after an 1860 meeting to discuss the abolition of slavery was attacked by supposed gentlemen in that civilised northern US city, ‘Liberty is meaningless where the right to utter one’s thoughts and opinions has ceased to exist. That, of all rights, is the dread of tyrants. It is the right which they first of all strike down. They know its power… Slavery cannot tolerate free speech. Five years of its exercise would banish the auction block and break every chain in the South.’

Many other history-making movements and individuals have demonstrated that if not for the fight for free speech, other freedoms would not be possible. Without the ability to argue your case there would be no way to clarify your aspirations, make clear your demands, or debate how best to strive for them.

More recent struggles for freedom and equality within Western societies have been intimately bound up with freedom of speech. The demand for their voices to be heard has proved central to the struggles for women’s emancipation, gay liberation and racial equality in the UK and US. There is a grim irony in the fashion for feminist, trans or anti-racist activists today to demand restrictions on free speech as a means of protecting the rights of the identity groups they claim to represent. Without the efforts of those who fought for more free speech in the past, these illiberal activists would not be free to stand up and call for less of it in the present.

We should remind ourselves also that free speech has to involve the freedom to challenge the most ardent orthodox beliefs of the day. That is why the essence of free speech is always the right to be offensive. Those who would deny the freedom of others to break taboos, offend against the consensus and go against the grain of accepted opinion would do well to remember where we might be without it.

Anybody suggesting now that the Sun circles the Earth would be accused of insulting our intelligence. Yet even four centuries ago, the notion of God’s Earth orbiting the Sun as a mere satellite and acolyte was among the most offensive ideas possible to Europe’s ruling religious and political powers, and they condemned those who suggested it as heretics.

It would be hard to imagine anything more offensive in 21st-century Western society than trying to deny votes to women or demanding the reintroduction of legalised slavery. Yet not so very long ago, those who opposed such oppression were being arrested and worse for offending against the state or nature.

The right to be offensive is above all about having the liberty to question everything; to accept no conventional wisdom at face value; to challenge, criticise, rubbish or ridicule anybody else’s opinion or beliefs (in the certain knowledge that they have the right to return the compliment to you).

That struggle for the freedom to offend against conformism and convention has been key to human progress and the advance of our collective culture and society through modern history. What, after all, would be the point of freedom of speech and of the press if you were only at liberty to say what somebody else might like? How could it be a right if it was withdrawn the moment you chose to use it to say what others consider wrong?

Thus has free speech become the voice of individual choice, scientific truth, and political progress – as well as, of course, offensive jokes, insults, cartoons and tweets. If we forget why free speech matters so much, and allow its standing to be sunk in a deluge of ifs and buts and not-too-fars, we risk undermining the foundations of civilisation and ruining any prospects of building on them further. Remembering the value of the freedom to think what we like and say what we think should lead us to demand more of it, rather than less. With, yes, no limits.

Mick Hume is spiked’s editor-at-large. His book, Trigger Warning: Is the Fear of Being Offensive Killing Free Speech?, is published by Harper Collins. (Order this book from Amazon(USA) and Amazon(UK).)

Mick will be giving the Battle of Ideas 2015 welcome address: ‘Je suis…what? Free speech after Charlie Hebdo’ on 17 October. Get your tickets here.

Who funds spiked? You do

We are funded by you. And in this era of cancel culture and advertiser boycotts, we rely on your donations more than ever. Seventy per cent of our revenue comes from our readers’ donations – the vast majority giving just £5 per month. If you make a regular donation – of £5 a month or £50 a year – you can become a and enjoy:

–Ad-free reading

–Exclusive events

–Access to our comments section

It’s the best way to keep spiked going – and growing. Thank you!

Comments

Want to join the conversation?

Only spiked supporters and patrons, who donate regularly to us, can comment on our articles.