Invasion of the sexbots? Get a grip

The sexbots are not coming.

In 1988, before the internet arrived in anybody’s house, I helped lead Britain’s first study of e-commerce – what was then known as ‘teleshopping’. I worked with British Airways, BT and other firms to see whether people would buy goods and services through computers. Near the end of the project, I dined with a senior journalist from the Daily Telegraph to talk about it. As prawn cocktails were served, he asked his first question. ‘Won’t giving people the power to shop through IT lead to an explosion of satellite pornography?’, he ventured. After that, the interview pretty much collapsed.

I learned then that large parts of the media have an in-built tendency to see IT, ironically, in digital terms. IT is either pure black, and full of doom; or it’s pure white, and will magically ‘empower’ everyone, at no cost, in an instant. Outright technophobia and technophilia leave no room for, er, shades of grey.

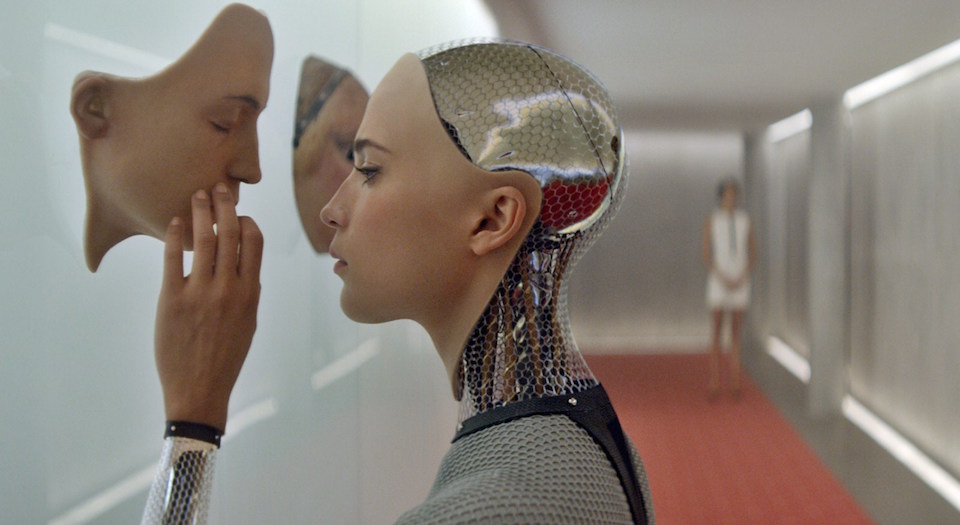

So it is with robots nowadays. And so it is with the media’s new scare-story-come-love-object: sexbots.

Kathleen Richardson, a specialist in the ethics of robots at the University of De Montfort in Leicester, has attacked what’s described as a new generation of sex toys – robotic ones. She’s even launched the Campaign Against Sex Robots, to protest their likely objectification and reinforcement of sex-role stereotypes.

Richardson is not the only one scaremongering. In a column for the Guardian, Plymouth University visiting professor Sue Blackmore argues that to programme IT-based machines to take ethical constraints into account when making decisions is fruitless, because such machines are already ‘beyond our control’. Artificial intelligence (AI), she says, has started ‘evolving for its own benefit, fed by our phones, drones and CCTV’. It’s not a ‘super-intelligent’ machine that we should worry about, but ‘the hardware, software and data we willingly add to every day’.

From this, we can only conclude that all-seeing, all-dancing sexbots are only a step away. Perhaps sexbots may have even begun skulking around Britain – it’s just that they’ve hidden themselves from us.

Now, let’s get a grip. Especially in today’s recession, newspapers need to sell copies. The same applies to universities: they need to get themselves in the papers to get research funds. And some of these critics aren’t all they seem. Blackmore’s original area of expertise was the paranormal, she practises Zen and is an honorary member of the Malthusian anti-immigrant lobby group Population Matters. So obviously she can be relied upon to take a balanced view of AI.

Blackmore’s view, she tells us, ‘rests on the principle of universal Darwinism – the idea that wherever information (a replicator) is copied, with variation and selection, a new evolutionary process begins’. First, we had replicator genes; then we had memes – when humans began to imitate each other and habits, skills, stories and technologies are copied, varied and selected. And now we’ve built machines that can copy, combine, vary and select ‘enormous quantities of information with high fidelity far beyond the capacity [sic] of the human brain’. These third replicators, we’re told, are techno-memes, or temes; and while our brains are just ‘billions of interconnected neurons’, AI is emerging ‘with gazillions of interconnections’, and ‘we need to worry right now’. Why? Because AI ‘is already evolving for its own benefit – not ours. That’s just Darwinism in action.’

So: biology, human culture and the lifeless world of electrons all follow the same pattern. The principle of Darwinism’s universality needs only to be asserted for it to be true. Blackmore’s dazzling Theory of Everything attributes the same blind laws to genetics, the writing of novels and ‘gazillions’ of CCTV cameras. According to such a view, a sexbot judging his or her partner to be the ‘wrong’ type could very easily have the will, emotions, aesthetic nous and sense of poetic justice to go berserk in bed.

And still the mass media go on publishing this rubbish. They have every right to; but we also have the duty not to believe them.

In 1984, I co-organised an exhibition at the Victoria and Albert Museum about robots, and co-wrote Robots, a short book about them. That book upheld the potential and capabilities of the rather primitive, largely automotive welders, sprayers and assemblers of their day; but it also warned that really sophisticated robots would be a long time coming:

‘Robots are a quantitative, not a qualitative, improvement on “computerised arms” introduced 20 years ago. Tools – the business end of robots – work more precisely; the sensors in and around tools are more sophisticated; the electronics have become microelectronics… But that is all… Robots process information. But so, to a lesser extent, do the toy-like automata with which people have entertained themselves since ancient times.’

I still hold by this. Today’s robots are smaller, more sophisticated and less ham-fisted than their predecessors; but they’re not going to turn us on in a hurry, nor are they likely to turn against us. A sexbot is a glorified vibrator, with controls more advanced than buttons and maybe less of a hum. That’s the long and the short of it, folks.

And yet still the technophiliacs and technophobes can’t help themselves, betraying the kind of imagination that robots will never emulate, but which we have heard from breathless pundits a hundred times. On the one hand robots are supposed to be growing so clever, some worry that they may soon deserve rights. It can’t be long before experts imagine that sexbots will deserve the kind of rights that are nowadays sought for sex workers.

On the other hand, robots, when they are not seducing us, are supposed to be taking our jobs. It doesn’t matter that UK productivity has slipped even further towards the bottom of the developed world, as the use of immigrants, women and older people by far outweighs the deployment of new machines. It doesn’t matter that, at 5.1 per cent, unemployment in the US is at a seven-year low. It doesn’t matter that investment (automation included) is weak throughout the West, that the cash hoarded by IT companies speaks volumes about their unwillingness to take robots much further, that the 225,000 robots sold worldwide in 2014 merely match the number of new jobs typically created in the US in just one month. People still insist that robots and IT generally are about to change the workplace forever, create mass unemployment and heighten inequality.

Do they live in the real world? Have they ever experienced IT? In go-ahead Britain, the government has pledged £150million to ridding the country of ‘notspots’, or places where mobile networks fail to operate – yet so far, a grand total of eight new masts have been built. In go-ahead Britain, you can barely get wifi access on a train. Not much speed of innovation there. Sexbots? Believe them when you see them.

James Woudhuysen is editor of Big Potatoes: the London Manifesto for Innovation. Read his blog here.

James will be speaking at the sessions ‘New wars, new technology’ and ‘Welcome to the Drone Age?’ at the Battle of Ideas festival in London on 17-18 October. Get your tickets here.

To enquire about republishing spiked’s content, a right to reply or to request a correction, please contact the managing editor, Viv Regan.

Comments

Want to join the conversation?

Only spiked supporters and patrons, who donate regularly to us, can comment on our articles.