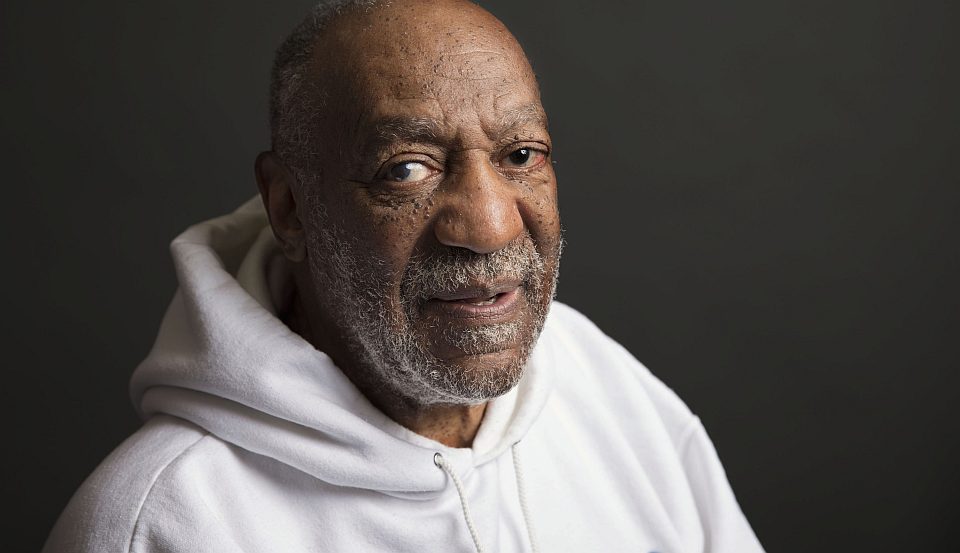

Cosby: convicted by social-media showtrial

The Cosby case confirms the ideal of justice is in a parlous state.

Want to read spiked ad-free? Become a spiked supporter.

Bill Cosby is back in the news. After becoming one of the dozens of women who have accused Cosby of sexual abuse, former model Janice Dickinson is at the forefront of calling for the statute of limitations, which prevents certain offences from being tried after a certain passage of time, to be repealed. The UK has no such statute, which is why the British police are able to pursue suspects many years after criminal events are alleged to have taken place.

Cosby’s case has received renewed attention in recent weeks because of documents released by US courts. In a 2005 court case, Cosby is said to have admitted to giving a 19-year-old woman sedatives in 1976 before they had sex. The drugs were given to him on prescription. These revelations, emanating from a case that Cosby eventually settled on undisclosed terms, were reported by the US media as proof that Cosby had drugged and raped at least one person in the past.

The revelations contained within the court papers, which only proved that Cosby did something completely legal with a woman almost 30 years ago, caused all of the great and good to chip in with their own Twitter testimony. Filmmaker Judd Apatow took to the Twitter stand, calling on people to ‘stand with the victims’ of Cosby’s attacks. One of Cosby’s alleged victims said in an interview that the revelations gave her ‘complete validation’.

‘Validation’ is highly significant in the discussion of Cosby. Today, validation has taken the place of justice. The purpose of making an allegation against someone is now less about obtaining justice or resolution than it is about obtaining social validation for alleged victims. This shift, from justice to validation, means that fairness and objectivity can be treated as mere obstacles to reaching the ‘right’ result for the alleged victims.

The question of the statute of limitations is largely academic in this discussion. Cosby’s detractors have bypassed the statute of limitations, along with all the normal requirements of proving one’s case, by subjecting Cosby to their own form of justice. In the social-media showtrial that has unfolded in recent months, Cosby has already been convicted and punished. Without any protections of due process, without any opportunity to test the evidence against him, he has lost his entire reputation, along with network deals, TV specials and charitable positions.

He is by no means alone. In fact, it is becoming common today for people to air allegations of sexual offending in the most public way possible, in order to do as much damage as possible, without ever having the allegations tested. In the UK, allegations of child abuse levelled in the past week at the deceased former prime minister Edward Heath are just the latest in a string of examples. Worse, we live in a time when this form of resolution is becoming the norm. Truth is no longer something that is established through legal processes. The truth is what people say is true. If enough mud is thrown, enough sticks. People’s lives can be thrown into disarray and their reputations ruined on the basis of rumour and gossip.

This is not to blame those making complaints against Cosby. In fact, Dickinson herself has said that all she wants is for a jury to try Cosby, and to have her allegations properly tested in court. It may well be true that Cosby’s sexual behavior in the past was questionable. It may be that these women feel violated by what has happened to them. And they should have all the emotional support that they need in order to move past these experiences. The problem is that these allegations are now served up for public titillation and broadcast on the world stage. Worse still, this titillation has taken the place of the sort of formal resolution that is no longer available to Cosby’s accusers.

This situation begs a huge question: what is justice for? The idea that people who stand accused of something have the right to have those allegations tested is being fundamentally undermined by this new form of public showtrial. In the past, showtrials were used by authoritarian governments to establish a ‘truth’, which was convenient for their political purposes. Today, the showtrial is used to validate and confirm the experiences of those making accusations. The showtrial has become the most effective way of telling people that their story has been believed by society at large, even when the laws of that country prevent a formal trial from taking place. In a society in which such therapeutic validation has become so central, what value do we accord justice, fairness and objectivity? Principles which have, for centuries, been cornerstones of Western systems of justice are now being done away with.

Of course, fairness and due process have faced their challenges in the past. But today the challenge does not come solely from over-powerful states. It comes also from informal tribunals in the news media and across the internet. These showtrials are, in some ways, even more damaging than the state-run showtrials of the past. At least there was the potential for over-reaching state powers to be held to account. Today, the social-media showtrial is run by people who are completely unaccountable. Even when their stories are contradictory and apparently ill-founded, they remain at liberty to dictate the resolution of their allegations on their own terms.

The Cosby case shows that there is no law that cannot be bypassed, no traditional protection that cannot be undermined, in the climate of panic and hysteria that now surrounds sexual violence. Slowly but surely, the current panic is picking away at the key protections that citizens have against the power of the state. It does this by moving the forum of punishment away from the official organs of justice and into the informal tribunals of Twitter and the media. In these new tribunals, allegations can be elevated to truth. Whatever sympathy we may have with those who believe they have been the victims of sexual violence, this new media-based totalitarianism has no place in a civilised society. Cosby deserves the protections of the laws he lives under, even if those laws produce results which the moral crusaders of the Twittersphere don’t like.

Luke Gittos is law editor at spiked, a solicitor practicing criminal law and convenor of the London Legal Salon. His first book, Why Rape Culture is a Dangerous Myth: From Steubenville to Ched Evans, is released on 1 September. (Pre-order this book from Amazon(UK))

Picture by: PA Images

Who funds spiked? You do

We are funded by you. And in this era of cancel culture and advertiser boycotts, we rely on your donations more than ever. Seventy per cent of our revenue comes from our readers’ donations – the vast majority giving just £5 per month. If you make a regular donation – of £5 a month or £50 a year – you can become a and enjoy:

–Ad-free reading

–Exclusive events

–Access to our comments section

It’s the best way to keep spiked going – and growing. Thank you!

Comments

Want to join the conversation?

Only spiked supporters and patrons, who donate regularly to us, can comment on our articles.