The ASA: Torquemada meets No More Page 3

The Advertising Standards Authority has become a censorious tyrant.

Guardians of moral decency have always had a penchant for policing flashes of women’s flesh. Whether it was Victorian moralists expecting all women to be draped from head to toe, or the British Board of Film Censors in the mid-20th century calling on filmmakers to ‘reduce to an absolute minimum’ any shots of women’s breasts and thighs, or Mary Whitehouse railing against a 1970s TV show in which a woman is shown ‘shaking her breasts before a man!’, controlling the depiction of women’s bodies has long been on the to-do list of prudes and censors. Yesterday’s ruling by the UK Advertising Standards Authority suggests this top-down urge to cover up the ‘wrong’ kind of women’s flesh is still alive and kicking.

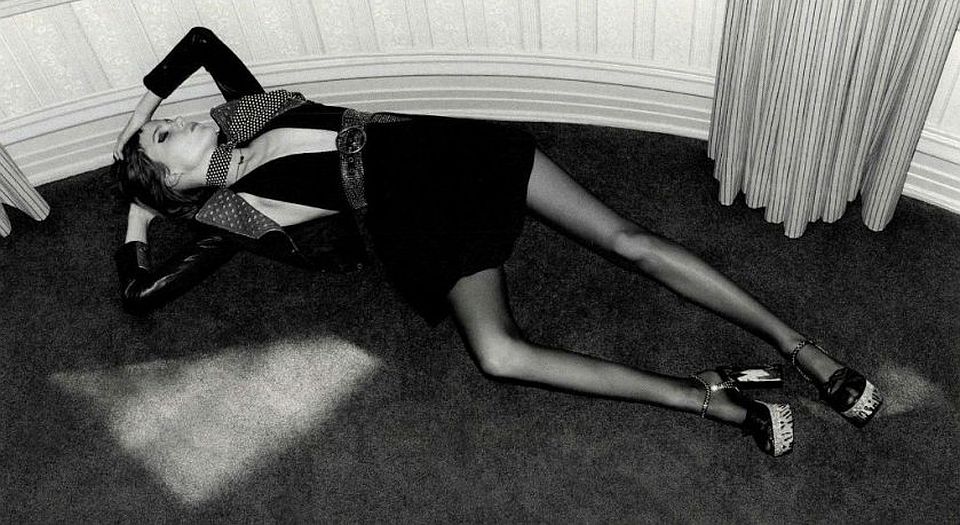

The ASA has banned an advert for Yves Saint Laurent on the basis that the model in it appears ‘unhealthily underweight’. Showing thin female bodies is apparently ‘irresponsible’. The ad, which appeared in Elle, featured a model lying on a floor in YSL clobber, her hand running through her hair, her chest (but not breasts) visible through a slit in her dress. With all the forensics with which a BBFC suit might once have timed how long a woman’s nipple appeared on screen, and whether its appearance was culturally justifiable, the ASA castigated both ‘the model’s pose’ and ‘the particular lighting effect’. It said the lighting meant the model’s ‘rib cage was visible’. It even policed what the model was wearing, drawing attention to ‘the contrast between the narrowness of her legs and her platform shoes’, which combined to make her legs look ‘very thin’. Showing such a lithe body is wicked, it seems, so the ASA decreed that the ad ‘must not appear again in its current form’. That is, it’s banned: a woman’s body has been hidden after officials decided that it was unacceptable, unpalatable.

This isn’t the first time the ASA, which enforces advertising codes in Britain, has used a metaphorical black marker to scribble out the ‘wrong’ kind of woman’s body. It’s currently investigating whether those Protein World ads that caused such a fuss in April, with their image of a model in a yellow bikini asking ‘Are you beach body ready?’, were ‘socially irresponsible’. In 2011 it banned an online ad for a bikini — after receiving just one complaint! — on the basis that the model’s ribs were ‘highly visible’. (Censors were once outraged by highly visible nipples or vaginas — now it’s highly visible ribs or collarbones.) Last year it banned a lingerie advert for the hipster clothes store Urban Outfitters, on the basis that there was a ‘significant gap between the model’s thighs’. Old moralists crushed images of buttocks or boobs; new moralists outlaw images of thigh gaps and thin legs.

Strikingly, the ASA justified all these bans on images of women, not on sexual grounds, but on health grounds. Where once images of women’s flesh were considered ‘morally corrupting’, now they’re described as ‘socially irresponsible’. The fear of the breast and bum, and the impact they might have on men’s minds in particular, has been replaced by disgust for the thigh gap or the pronounced collarbone, and the impact such flesh (or lack thereof) might have on impressionable girls and women. But whatever the justification, whether it’s the sexuality or svelteness of women’s bodies that is being policed, and whether this censorship-of-the-female is done to placate God and encourage moral control or to promote public health, the result is the same. In fact, both the instinct and the impact of the old censorship of sexual women and the new censorship of thin women are the same: the instinct is to define what kind of woman’s body it is acceptable to show, and the impact is to patronise the public, reducing us to the level of children whose eyes must be guarded against either big breasts or thin chests.

The mission creep of the ASA has been astonishing. This is a body that is supposed to keep an eye out for dodgy claims in ads — this tincture will cure your impotence! etc — yet which in recent years has become a kind of cross between Torquemada and No More Page 3. It banned a TV ad for the fruit drink Oasis on the basis that its slogan — ‘for people who don’t like water’ — might ‘discourage good dietary practice’. A measly 32 people complained about that ad. It banned a TV ad for hair products, which featured models dressed as nuns, on the grounds that it was offensive to Christians (it was to 23 of them, the number of complaints received). It banned an ad for a supermarket which showed a girl taking the salad out of her hamburger before eating it, on the grounds that it ‘disparaged’ healthy eating. Disparaging good health! Imagine that. It’s the equivalent of blasphemy in these five-a-day, chip-dodging times.

The burger episode followed by the YSL episode shows just how screwed-up is the ASA, and the rest of British officialdom. On one hand they panic about children being encouraged to eat ‘junk food’, and on the other they strictly police images of skinny women. It’s a kind of schizo-censorship: ‘Don’t show people enjoying burgers — the stupid public might feel free to get fat! Oh, but being thin is really bad, too. So don’t show thin people, either.’ With such mixed messages from the self-elected overlords of public morality, it’s no wonder some kids have body-image issues.

With its growing forays into the policing of female imagery, the ASA’s true censoriousness is becoming clear. For what we can see in these health-justified clampdowns on fashion ads and posters with bikini-clad women is the crashing together of the old moralism and the new moralism, an unholy marriage of the Victorian instinct to hide ‘bad’ women’s bodies with the new PC urge to educate the public about the right way to eat, look and, fundamentally, be. Across the West, we’re witnessing a shift, a scarily seamless one, from an older era in which censorship was justified as a means of controlling our sexual desires or political thoughts to a new era in which censorship is designed to protect apparently isolated, vulnerable individuals from the harm of ill-health or any challenge to their self-esteem. The Victorian-style censors who wanted to hide away sex and sauce have been usurped by left-leaning, feministic censors who want to cover up what they view as sexist imagery, or unhealthy imagery, or esteem-rattling imagery.

The end result? That, alarmingly, we still live in a world in which women’s bodies are considered disturbing, deviant things, and in which all of us are infantilised by those who think they know what we should be allowed to see, hear and talk about.

Brendan O’Neill is editor of spiked.

To enquire about republishing spiked’s content, a right to reply or to request a correction, please contact the managing editor, Viv Regan.

Comments

Want to join the conversation?

Only spiked supporters and patrons, who donate regularly to us, can comment on our articles.