Did the Tories really win?

And other unanswered UK election questions.

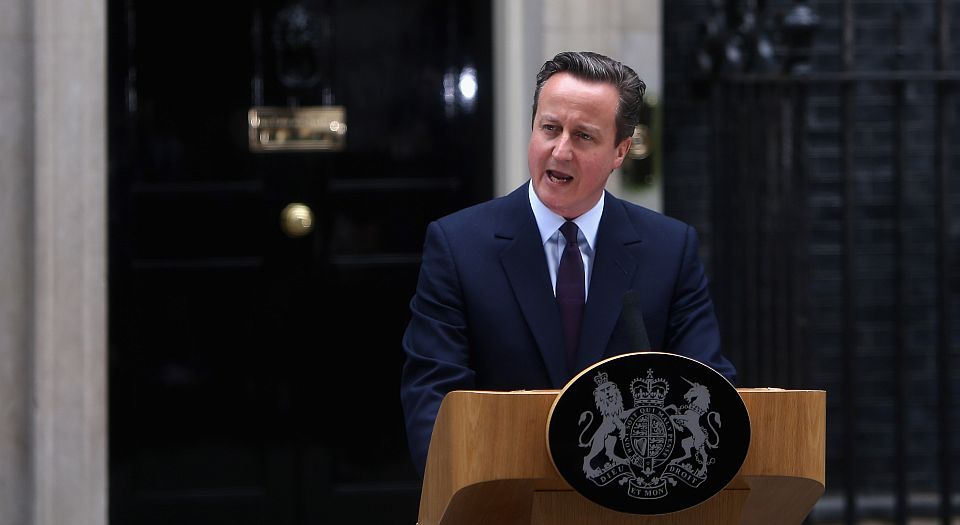

Before the UK General Election we were told that the outcome was going to be the most uncertain in recent memory, and nobody was sure what to say about the likely results. Now that the Conservatives have confounded the opinion polls and achieved a small overall majority of MPs, there is much talk of David Cameron’s Tories having won a decisive victory. In truth, there is much that the results have not decided. In the immediate aftermath some big questions are left hanging.

Labour and the Lib Dems have lost decisively, but have the Tories really won?

The outcome of the 2015 election looks like a dramatic win for the Tories. Polls had shown Cameron’s party neck-and-neck with Ed Miliband’s Labour Party throughout the campaign, and everybody seemed sure the result would be a hung parliament. Instead, the cock-a-hoop Conservatives have ended up with a slight overall majority, boasting that they are the first incumbent party to increase its number of seats since Margaret Thatcher’s Tory government did so in 1983.

Yet what does the Tory victory amount to? The party has increased its share of the vote since 2010 by just over half of one per cent – from an unspectacular 36.05 per cent to 36.7 per cent. Some polls had the Tories on that sort of mark during the campaign, while the ‘poll of polls’ tended to have them hovering around an average of 34 per cent. That extra couple of points hardly looks like any dramatic ‘late breakthrough’.

It might be useful to step back from the intense focus on the immediate results and put things in a bit of historical perspective. Last time the Tories won a parliamentary majority, way back in 1992, John Major got 41.93 per cent of the vote. Go back further to when UK politics was a two-party system and the contrast is even starker. When the Tories lost to a Labour landslide in the famous postwar election of 1945, Winston Churchill’s Conservatives still won 40.26 per cent of the votes cast. Five years later, when Labour won a tiny majority, the losing Tories received 43.44 per cent of the vote – the sort of support that the ‘triumphant’ Cameron, aka Mr 36.7 per cent, can only dream of.

An ordinary Tory performance looks special this time only because of the collapse of the other two traditional national parties. The Liberal Democrats slumped to eight seats and less than eight per cent of the vote, a far cry from 2010 when they won 57 seats with 23 per cent. Unsurprisingly, having gone from being the outlet for public dissatisfaction with mainstream politics to the Tories’ partners in government, the Lib Dems lost all of their protest votes this time around.

Far more surprising to many was the fate of the Labour Party, the biggest losers of 2015. Until the eve of the election it appeared Labour’s leadership entertained serious hopes that the ‘Milibrand’ would carry the party into government. In the event it won just 30.7 per cent of the vote. That is a slight increase from the miserable 29 per cent who voted for Gordon Brown’s party in 2010, yet Labour managed to win even fewer seats this time. Only in London did Labour show any signs of life. It has been reduced to one MP in its former stronghold of Scotland, and suffered elsewhere. Having tried to play safe and appeal to ‘core’ Labour voters on issues such as the NHS, Miliband and Co discovered that their core has rotted away. UKIP took big bites out of the Labour vote even in northern England, eventually finishing second in more Labour seats than Tory ones.

Again, a bit of history helps to put things in perspective. Back when Labour lost to Churchill’s Tories in 1951, it still won 48.78 per cent of the vote. When Tony Blair’s New Labour triumphed in 1997, he was elected with 43.2 per cent. Indeed, for all its 2015 pre-election hype, Labour has achieved lower votes than Miliband’s only twice in modern electoral history – in 1983 and 2010. Beyond the debate about who the next Labour leader should be, this election surely raises questions about the future of the zombie Labour party itself.

If ‘the people have spoken’, who’s listening?

Before the election there was worried talk in high places about a ‘legitimacy crisis’ if a minority Labour government was to be propped up by the Scottish Nationalists. Now there are sighs of relief in the media and the financial markets about everything being resolved and stability ensured by the Tory victory. Yet despite its statistical win the new Conservative government, like the coalition before it, will still face a crisis of public political authority. It can hardly claim a popular mandate to represent the will of the people, most of whom either did not vote for it or did so to stop Labour and the SNP.

Turnout in this election reached 66 per cent, up slightly on 2010 (65.1 per cent). Yet that still makes 2015 the fourth lowest since 1918. Indeed, the four lowest turnouts have been in the past four General Elections. In real terms, this means that Cameron’s Tories won the support of only around 24 per cent of all those who could have voted. The ‘none of the above’ party of non-voters totalled 34 per cent, finishing a close second this time. Millions of those who did vote will feel no more represented than those who did not, notably the almost five million UKIP voters who ended up with one MP between them.

The authority crisis is not just an arithmetical problem, but a political problem. Neither the Conservatives nor any other party has the sort of roots in UK society they once had. None of them represents the distinctive interests of classes and constituencies as they once claimed to do. A shallow media-obsessed election campaign, in which no major party stood on a programme informed by clear principles, provides a shaky basis for Cameron or anybody else to claim to rule and take hard decisions in the name of the people.

Disunited Kingdom, but is Scotland so different?

After last year’s referendum on Scottish independence, I wrote on spiked that ‘we’re all in the non-UK now’. Despite the eventual ‘No’ vote, the referendum campaign starkly exposed the absence of anything in terms of wider values or principles that could hold the UK together. We predicted a descent into even more parochial, narrow-minded politics. That has apparently been borne out in the General Election which, as others have observed, leaves the Tories as the ruling party in England, the SNP in Scotland, Labour in Wales and the DUP in Northern Ireland.

The key factor in this is the reaction against the failed centre of British politics, more than a genuine upsurge in popular nationalism or regionalism. That is the case even in Scotland, where the SNP has swept the board, winning a remarkable 56 out of 59 seats. As Frank Furedi argued on spiked recently, the SNP essentially won by playing the anti-politics card. Nicola Sturgeon’s campaign pulled off the feat of presenting the governing party in Scotland as an insurgent party of protest.

Yet the underlying anti-Westminster sentiment is the same as that felt elsewhere today by millions, shared by everybody from UKIP or Green voters to those who voted reluctantly for the ‘lesser evil’ or did not bother voting at all. If there had been the same excited prospects of success, it would not be too hard to imagine an SNP-type uprising against the centre elsewhere in England or Wales.

As I noted after the Scottish referendum, the anti-Westminster mood ‘might sound like a good thing. The trouble is, however, that simply sticking two fingers up to the Westminster oligarchy provides a slender basis for a common political outlook. If all people have in common is a rejection of the centre, it is no surprise to see them divide against one another and retreat into parochial and sectional concerns.’ Expect to see more post-electoral attempts at moving the constitutional deckchairs around on the deck of HMS UK, and re-dividing the household budget between warring family members, retreating from the necessary debate about what might unite us in a future-oriented society.

New faces – but what will change?

There appears to be a wind of change blowing through British politics. There will be many new faces in the next parliament, none newer than the 20-year-old student who is now an SNP MP, replacing tired old ‘big beasts’ from Labour and the Lib Dems. Labour, the Liberal Democrats and UKIP will all have new leaders soon. Many might watch the fall of the likes of Labour’s Ed Balls with the thought that it could not have happened to a nicer bunch of people, and that any change has to be for the better.

But what’s new in politics? The Tories have been returned to government having stood without clear principles or plans for change. They presented themselves as the most boringly proficient accountants, in a contest between managerial politicians each claiming to be the safest pair of hands to run the shop. It should have been no great shock that they eventually beat the Labour Party in such a contest. But little is likely to change as a consequence. As Phil Mullan showed earlier this week, the all-important issue of the future prosperity of the UK economy did not even feature as a subject of debate in the election campaign.

Our ‘new’ leaders have no more clue of what to do about changing Britain for the better than they had about the outcome of the election. Those hoping to see much in the way of fresh politics are advised not to hold their breaths for the next five years.

What planet is the political class on?

The most important gap highlighted by the 2015 election campaign was not that between the parties, but the one separating our elitist political class from the people it claims to represent. The relationship of the politicians to the public has rarely been more marked by an attitude of distance and disdain.

The leaders of all the major parties today operate as part of an isolated oligarchy, cut off from society within their private bubble, if not on another planet. That was why, despite all their expensive private polling and claims of extensive canvassing, they were all left so shocked by the exit polls and the final results, the Tories apparently as surprised as Labour to discover that they had actually achieved a majority of seats. As the results became clear early on Friday, Labour’s leadership team effectively withdrew from the media fray, not having a clue what was happening or what it could say about it.

It was not long, however, before all the losers started to come out with a familiar script of blaming the electorate down on planet Earth for their defeat. There was much talk of how the Tories and the SNP had both used fear of the other to scare impressionable voters into supporting them, like trainers blowing a dog whistle to which dumb mutts will respond. Social media were inevitably full of attempts to blame the Tory media, especially the Murdoch press, for allegedly brainwashing the idiot voters into backing Cameron. The online elitists might do better to reflect on how the election confirmed another gap – between their imaginary world on Twitter and other social media, where the likes of Labour and the Greens always win, and the real world where most voters live.

To paraphrase Bertolt Brecht, perhaps it would be simpler if our disappointed politicians simply dissolved the people, and elected another.

Mick Hume is spiked’s editor-at-large. His book, There is No Such Thing as a Free Press… And We Need One More Than Ever, is published by Societas. (Order this book from Amazon(UK).) Visit his website here.

To enquire about republishing spiked’s content, a right to reply or to request a correction, please contact the managing editor, Viv Regan.

Comments

Want to join the conversation?

Only spiked supporters and patrons, who donate regularly to us, can comment on our articles.