Tower Hamlets: the tyranny of fake ‘anti-racism’

If only Lutfur Rahman had been toppled by debate rather than a judge.

Want to read spiked ad-free? Become a spiked supporter.

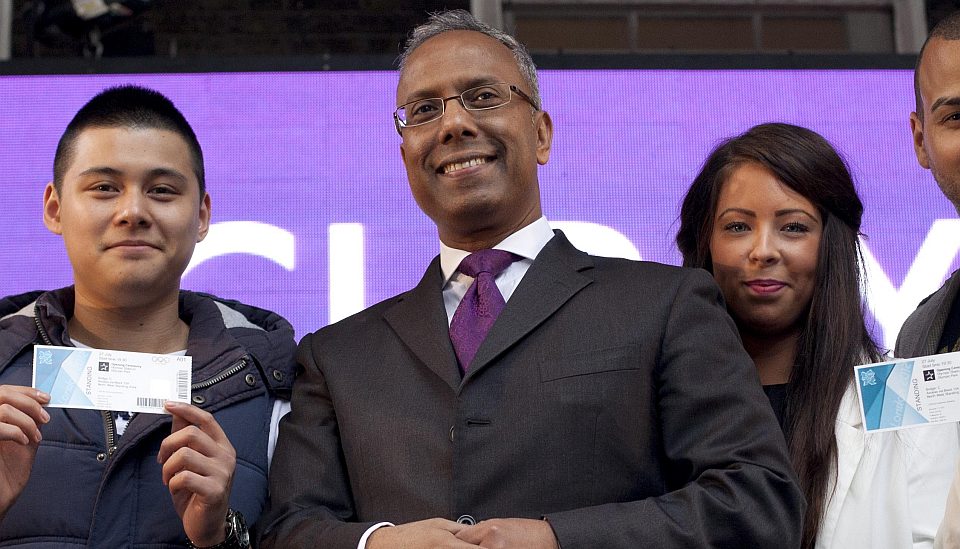

Lutfur Rahman won local elections in 2010 and 2014 to become mayor of the London borough of Tower Hamlets. Last week, his 2014 election victory was voided by a court on grounds of his electoral corruption, bribery and cheating. The High Court’s judgment is both enlightening and troubling. It’s enlightening because it exposes the prevalence of fake anti-racist politics in a borough where 35 per cent of the electorate are from the Bangladeshi community. And it’s troubling because it reveals the inability of mainstream politics to deal with the politics of anti-racism. After all, Rahman was dethroned not by the strength of his opponents’ political arguments, but by legal strength of a High Court judge.

No doubt racism still exists in society, albeit with nothing like the social force of earlier decades. But today there is a problem with much greater social force: anti-racism. Its proponents see racism where none exists. They see it in order to skew or close down debate. By playing the race card, these anti-racists can promote their own views, which are informed by the politics of identity and pity – and, in Lutfur Rahman’s case, a large measure of personal aggrandisement as well.

Over the course of the five-week-long trial, which came to court because four aggrieved local electors challenged Rahman’s 2014 election victory, the judge heard evidence about local politics in Tower Hamlets dating back to the 1990s. After subjecting this evidence to forensic scrutiny, he gave a damning judgment on the politics of anti-racism. He had no difficulty seeing the fake anti-racism that Rahman had practised over many years. He concluded that Rahman had ‘relied on silencing his critics by accusations of racism and Islamophobia’. How did he reach this conclusion?

The judge’s reasoning is worth going through in some detail (you can read the 100-plus-page document here). Central to his judgement was the way in which anti-racists since the 1990s have hyped up the far right. In Tower Hamlets, racism has, for many years, been largely confined to a few marginalised boneheads who we know about because the practitioners of anti-racism need to draw attention to them. First came the racist British National Party, whose candidate, Derek Beackon, was elected as a Tower Hamlets councillor in 1993. Although unseated a few months later, ‘Beackon’s election was accorded a reaction bordering on hysteria both among other politicians in Tower Hamlets’ and in the media, the judge said. His election ‘was used, for decades afterwards, to justify the claim that racism stalked the borough’.

Next came the English Defence League (EDL), an organisation that ‘has long been negligible, verging on the non-existent’. Yet anti-racists needed the EDL, continued the judge, because when the EDL proposed to march through Tower Hamlets, as it did in September 2013, ‘the political and community organisations in the area normally vie with each other in demanding that the march be banned’. This was ‘an opportunity for each group to castigate the supposed half-heartedness of the others, to adopt a “more anti-fascist than thou” posture’.

With a dry wit, the judge described the utterly cynical basis of anti-racism by noting that ‘the march occurs; the assembled political and community groups stage their counter-protest; sometimes a few heads get broken. The police and (subsequently) the street cleaners deservedly earn substantial overtime. The dogs bark and the caravan moves on. Everyone congratulates themselves that they have “seen off the fascists”.’

The EDL disliked Rahman because he is Muslim and not white, and it routinely circulated any criticism of Rahman on social media. So, by the infantile politics of anti-racism, Rahman was able to argue the following: ‘[C]riticisms of Rahman by his political opponents are adopted and repeated by the EDL; the EDL is a racist organisation; therefore anyone who criticises Rahman is giving aid and comfort to the EDL: therefore anyone who gives aid and comfort to the EDL is himself a racist: therefore it is racist to criticise Rahman.’ The judge observed that this anti-racism was the ‘epitome of the thought processes’ of Rahman’s election agent. But the craving to hype up the EDL in order to establish their anti-racist credentials is the hallmark of all anti-racists. ‘If the EDL did not exist’, the judge continued, ‘truly, in Tower Hamlets… like Voltaire’s God, it would be necessary to invent it’.

Anti-racism feeds off pity directed at the perceived victims of racism, which in Tower Hamlets is the Bangladeshi community. So when Rahman set up his Tower Hamlets First party as an organisation with ‘no coherent political agenda beyond the personal aggrandisement of Rahman and the wellbeing of the Bangladeshi community’, Rahman’s anti-racist political opponents were floored. For they could hardly criticise Rahman for seeking to lavish pity on people who they also saw as the perceived victims of racism.

In fact, the Labour Party had already prepared the ground for Rahman’s corruption when, after winning the 1994 local elections on the back of the Derek Beackon hysteria, it reorganised Tower Hamlets’ staffing, ‘especially at senior levels’. The Labour left argued for ‘a wholesale purge of old staff and replacement by new [that] would enable the council to increase the number of employees recruited from the Bangladeshi community’. Those who opposed this staff reorganisation ‘could be denounced by the left as racists, trying to keep Bangladeshis from being employed at the town hall’. The judge drew attention to the significant yet fake nature of anti-racism: ‘Accusations of racism were the common currency of left/right infighting in the Labour Party but, viewed objectively, none of the participants was remotely racist in any sense that would be understood by a person not in the emotionally over-heated committee rooms in the town hall.’

So, when Rahman secured the mayoralty in 2010 he could build on the platform that the Labour Party had put in place. He could take his anti-racist politics of pity to another level by diverting substantial amounts of grant money ‘to organisations representing or serving the Bangladeshi or other Muslim communities’. As a report from PwC, commissioned by central government, found, ‘enormous sums of public money had been paid to organisations in excess of that which council officers had recommended and, in many instances, to organisations that had not even applied for grants’. For example, nearly £100,000 was ‘handed out to 10 organisations, all Bangladeshi or other Muslim organisations, for lunch clubs when none of them had even applied for a grant’. Rahman sought to justify these payments on the basis of ‘local knowledge’, but it would be more honest to say that, for anti-racists, a state handout is justified payback that assuages their sense of pity.

Rahman’s anti-racism was learnt in the Labour Party. He joined Labour in 1989, became a Labour ward councillor in 2002, and in 2008 became leader of the Tower Hamlets Labour Group. He only left the Labour Party after its national executive committee (NEC) failed to select him as its mayoral candidate in 2010 (and at all times since, he hoped to be readmitted to the Labour fold). But this decision was not made on the basis of any political difference between Labour and Rahman over the politics of anti-racism. That much is clear from the fact that after the NEC rejected Rahman as its candidate, it did not select the man who had come second in the local party ballot. The runner-up, John Biggs, was white, so the NEC imposed Helal Abbas, who had come third in the ballot. As one member of the NEC observed, the selection of Abbas was motivated by Labour’s desire ‘not to leave themselves open to the charge of deselecting a Bangladeshi and replacing him with a white man’.

John Biggs, a longstanding Labour Party member, did on occasion seek to resist the politics of anti-racism. But with anti-racism being so mainstream in the Labour Party and beyond, any principled stand Biggs took was always going to leave him marginalised. Back in 1998, he objected to Spitalfields being renamed Banglatown (as the Bangladeshi community called it). He lost this fight when the ward was renamed ‘Spitalfields and Banglatown’. In an interview on the BBC’s Sunday Politics programme, Biggs said of his soon-to-be opponent in the 2014 mayoral election that all Rahman’s ‘councillors are from the Bangladeshi community and the primary focus of his policymaking has been on the Bangladeshi community’. The judge found both parts of this statement to be true.

But truth didn’t satisfy Rahman, who deployed his modus operandi and claimed that Biggs had been ‘racially insensitive’. Worse followed after Rahman’s election agent reported Biggs’ comments to the Equality and Human Rights Commission (EHRC), whose senior solicitor wrote a response saying: ‘The commission agrees that you are rightly concerned about the remarks made by the Labour mayoral candidate… However…’ Readers who are expecting the ‘however’ to be followed by an endorsement of free speech will be alarmed by what actually follows: ‘However, such remarks should more appropriately be reported to the police’ as ‘incitement to racial hatred is a police matter’. Fortified by the EHRC’s indulging of his anti-racism, Rahman responded, once again, by accusing Biggs of racism and a press release from his election agent claimed that the EHRC was ‘rightly concerned’ about Biggs’ comments and that ‘the issue appeared to be a hate crime and therefore a matter for the police’.

Rahman played the politics of anti-racism skilfully and successfully. But he succeeded because so many of his political opponents accepted the politics of anti-racism. Rahman outplayed them by establishing that he was more ‘anti-racist than thou’, a mantle he was readily able to assume once he had become the bete noire of the EDL. His re-election in 2014 was fortified by his absence of scruples about using state handouts to buy votes, bribing journalists and using fake ‘ghost’ voters.

Rahman should have been toppled by a politics that sees anti-racism as phoney, that recognises that anti-racists use the far right to parade their own anti-racist credentials and that doesn’t look upon black and minority ethnic electors as objects of pity. In short, Rahman should have been exposed, not for corruption, bribery and cheating, but for the poverty of his politics. Few, except the diehard members of the politics of anti-racism, will regret the demise of Lutfur Rahman, but we should all note how his fall from the mayoralty has not been achieved by a public debate about the politics of anti-racism. It has been achieved by a judge laying down the law. Democracy deserves better.

Jon Holbrook is a barrister based in London. He was shortlisted for the Legal Journalism prize at the Halsbury Legal Awards 2014. Follow him on Twitter: @JonHolb

Who funds spiked? You do

We are funded by you. And in this era of cancel culture and advertiser boycotts, we rely on your donations more than ever. Seventy per cent of our revenue comes from our readers’ donations – the vast majority giving just £5 per month. If you make a regular donation – of £5 a month or £50 a year – you can become a and enjoy:

–Ad-free reading

–Exclusive events

–Access to our comments section

It’s the best way to keep spiked going – and growing. Thank you!

Comments

Want to join the conversation?

Only spiked supporters and patrons, who donate regularly to us, can comment on our articles.