Give us the freedom to build our own homes

We need 260,000 new homes a year, and officials won’t build them.

Want to read spiked ad-free? Become a spiked supporter.

Activist and comedian Russell Brand has recently been leading a protest at the Sweets Way Estate in north London, where more than 100 occupied houses had been emptied for a new development. The way that Brand told it, the evictions and the development were nothing more than profiteering, clearing poor people out and gentrifying neighbourhoods. Brand told the Guardian: ‘There are 1.5million empty buildings in the UK. The entire crisis of homelessness is a confection, a creation, unnecessary.’

Since there are only 610,000 empty homes in England, this is almost certainly an exaggeration. Further, only around 200,000 have been empty for more than six months, which suggests that the greater portion of empty homes are just empty because of the natural turnover.

The belief that there is no housing shortage, only profiteering by landlords and developers, is very strong. The numerically illiterate statistician Danny Dorling says as much in his book All that is Solid Melts into Air. There, Dorling asks if there really is a shortage of homes, and compares the number of rooms in buildings to the number of people, and discovers – lo and behold! – that there are plenty of rooms to put people in. Dorling says: ‘The perceived “national” housing shortage is in fact a regional shortage, part of the growing north/south divide. Everywhere there is vacant housing that needs to be used better.’

But vacant housing is not the reason that there is a housing shortage. Indeed, the number of vacant properties has been falling all the time that prices have been rising (that prices are rising is the reason that the numbers of vacant properties are falling). Dorling is saying that the pressure on homes in the north of England is not as high as in the south. But that is no use to people who live, because of work or family connections, in the south. In London, for example, there are 22,000 vacant properties (they are vacant for the most part because they are not currently habitable, or they are in the process of changing hands). But a slack of 22,000 homes in London is simply not enough to make any kind of dent in the housing need, even if by some miracle every home could be inhabited tomorrow.

For the past 20 years, politicians, commentators and activists have been burying their heads in the sand over the shortfall in new housebuilding to meet housing need. Those of us who have tried to draw attention to the problem – those of us at spiked; the housing economist Alan Evans; the Bank of England’s Kate Barker, who reviewed the question in 2002; the Institute of Economic Affairs, and a few others – have generally been shouted down as alarmists or the apologists of developers.

More recently, some commentators, notably the Labour Party-supporting Owen Jones and shadow education minister Tristram Hunt, have woken up to the problem. Conservative leaders like London mayor Boris Johnson, communities minister Eric Pickles and former housing minister Grant Shapps have also acknowledged a serious shortfall in the number of homes being built.

Labour has committed itself to a target of 200,000 homes to be built each year, if it is elected. The more radical Left Unity coalition that helped to organised a big rally for new homes says that it wants to see 250,000 new homes built each year. All of this is good news if it means that the political class is committed to turning around the shortfall in houses.

To restate the problem: There are 26.4million households in Britain, in as many dwellings. Assuming that each of these dwellings will stand for around 100 years, the country has to build 264,000 dwellings each year to replace the existing stock. But for more than 20 years now, the number of new starts has remained stubbornly around or below the 200,000 mark – which means that we are not even replacing the existing housing stock, let alone meeting the growth in households, which is pressing.

But because houses do stand for many years, not building enough does not create an immediate shortage. What it does mean is that the housing stock is ageing. Britain’s housing stock is the oldest in Europe: 55 per cent of UK homes were built before 1960. Not surprisingly, about a tenth of those decrepit houses and flats have leaking roofs or rotten windows (1). The Home Builders Federation worked out that at the current rate of building, each house in Britain would have to stand for 1,200 years before it was replaced. Of course, they will not stand for 1,200 years, even with all the resources that they absorb in repairs, redecoration and refurbishment.

But it is not just the replacement of existing stock that is failing. Between 2001 and 2011, the number of households grew by more than two million, which means two million more people whose housing needs are not being met by the pitifully low rate of housebuilding.

The consequences of the housing crisis that so many want to deny are plain to see. More overcrowding, dilapidated houses, new families unable to set up homes for themselves, and more and more people in emergency local-authority housing, living illegally in sheds, or sleeping rough.

The most obvious expression of the housing shortage is in prices. House prices have risen to a UK average of £189,000, while in London the average is £406,000. The reason that they are so high is because of the restricted supply, relative to demand. The impact of house-price rises is great. When prices go up, rents follow suit, averaging £753 a month UK-wide, and rising to £1,233 in London.

That more people are willing to talk about the housing problem is a great advantage. For many years, an unholy alliance of environmentally minded left-wingers and Tories in the Home Counties conspired to shoot down any suggestion of new housebuilding. In the Guardian, Ros Coward pleaded that there should be no ‘green light for the developers’, while Tristram Hunt warned against a ‘Tsunami of Concrete’ crashing over the Green Belt. Even the Socialist Worker got misty-eyed about the ‘threat to the planet’: ‘One application proposes building an eco-town with 5,700 homes in the centre of the National Forest in Derbyshire. Seven million trees have been planted in the forest since 1990 – many of these are now threatened.’

Against these hysterical warnings, a new willingness to put people before trees is to be welcomed. However, most of the proposals for new building are heavily qualified.

For instance, Owen Jones and architectural critic Owen Hatherley insist that housing need should be met by a return to council-house building. This is quite a proposal. Local authorities manage far fewer homes than they did in the past, and the direct works departments that built and repaired homes have largely been privatised. In principle, there is no reason why housing need should not be met by local authorities; but in all seriousness, most people would not trust the local council to run a newsletter, let alone take responsibility for organising people’s living space.

These critics have forgotten what a lot of bureaucratic snoops and control freaks council-housing officers were when they did have control of people’s homes. New Labour’s much-mocked and despised anti-social behaviour order (the ASBO) was based on the local-authority tenant agreements that empowered councils to evict people who did not conform to their ideal of community living. Registered social landlords today have far-reaching powers over their tenants, of the kind that people who bought their council houses under Tory prime minister Margaret Thatcher’s scheme were trying to escape.

To meet housing need through government construction and management programmes would suggest a spectacular revolution in public attitudes and local-authority organisation. You have to suspect that the argument that local authorities will build 250,000 homes a year is really just a way of kicking the ball into the long grass.

As well as floating unrealistic ideas about the capacity of local authorities to build homes, the more radical critics of the housing shortage hope that the planning system will deliver.

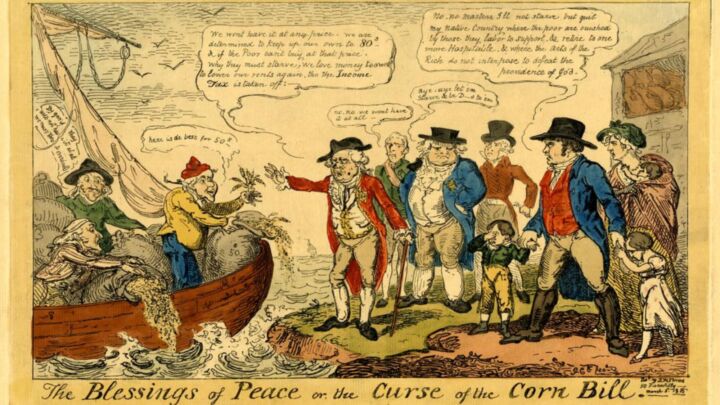

Ken Loach’s Left Unity group, which protested against the housing shortage, set out its policy: ‘Left Unity calls for a radical reform of the planning system, nationalisation of development rights.’ This is quite bizarre, since ‘development rights’ were nationalised in 1947 with the creation of the Town and Country Planning Act. Before then, you could develop land simply by right of owning it.

The ‘nationalisation of development rights’ in the 1947 Act has not, on the whole, acted as a spur to new building, but rather as a barrier. The planning system never worked as a positive promotion of development, but instead only empowered those who want to restrict it.

Planning is an excellent idea. What could be more reasonable than the whole country consciously deciding its plans and then getting to work achieving them? Unfortunately, the planning system in Britain is nothing like that. What goes by the name of planning is in fact the opposite: an unplanned chaos, where all consequences are unintended.

The reason people are talking about the housing crisis today is that it has come crashing about their heads, and can no longer be avoided (even though some people are still trying to).

Unfortunately, the solutions that have been raised so far carry the same underlying problem as the original evasion of the housing crisis. Rather than taking down the barriers to development, most critics are preoccupied with controlling the problem. Where bureaucratic limits on growth have brought us to the current impasse, these campaigners want to keep bureaucratic control of the way the problem is to be addressed.

The fantasy of a revived local-authority housing programme bears the hallmarks of a backward-looking fantasy of top-down dirigisme.

The real solution is to relax the planning system, even to abolish it altogether. Where the critics want to see government step in to manage people’s housing problems, the better answer would be to let people manage their own housing problems.

Currently, the cost of building a new house is around £90,000. But the average house price is more than twice that. The difference arises because of the restriction of land for development under the Town and Country Planning Act and subsequent legislation. Development rights should be taken out of the hands of those officials who withhold them, and handed back to the people.

Between the First and Second World Wars, hundreds of thousands of Britons built their own homes on spare land, called ‘plotlands’; better off, middle-class people bought cheap homes in suburbia. This was the greatest expansion of housing in Britain, and developed much of the south east. Excoriated by Tory snobs and urban intellectuals alike, this burst of ribbon development and plotlands was entirely free of government control, and all the more successful for that. Let’s build. Let’s build 260,000 homes a year. But do not expect the government or the local authority to build them for you. If you do, it just will not happen.

James Heartfield is a writer and researcher. His latest book, The European Union and the End of Politics, is published by ZER0 Books.

(1) Europe’s buildings under the microscope, Buildings Performance Institute Europe, 2011, p 35

(2) When economist Kate Barker first said that a housing shortage was bidding up prices, local government leaders and environmentalists insisted that was not true, blaming cheap credit. It was true that cheap credit contributed, but pointedly, the end of cheap credit in 2008 only had a short term effect on prices, which have returned to their pre-credit crunch levels

Who funds spiked? You do

We are funded by you. And in this era of cancel culture and advertiser boycotts, we rely on your donations more than ever. Seventy per cent of our revenue comes from our readers’ donations – the vast majority giving just £5 per month. If you make a regular donation – of £5 a month or £50 a year – you can become a and enjoy:

–Ad-free reading

–Exclusive events

–Access to our comments section

It’s the best way to keep spiked going – and growing. Thank you!

Comments

Want to join the conversation?

Only spiked supporters and patrons, who donate regularly to us, can comment on our articles.