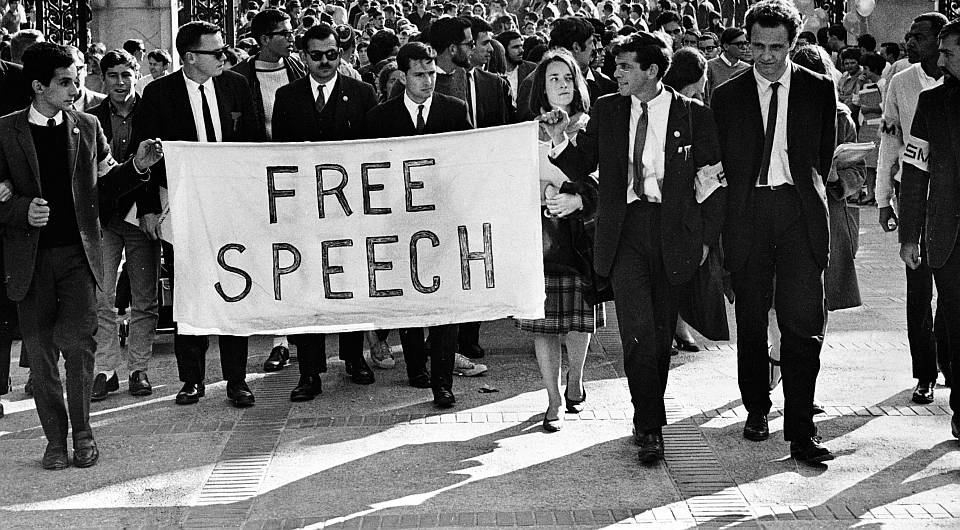

When students believed in liberty

Fifty years on from the Free Speech Movement, its veterans talk to spiked.

Want to read spiked ad-free? Become a spiked supporter.

In the early Sixties, student activists at the University of California, Berkeley, were forced to toe the line. With McCarthyism and loyalty-oath controversy casting a long shadow, the use of campus space to promote causes, sign up members to organisations and collect funds was tightly restricted. Only one spot, the campus entrance at Bancroft and Telegraph, remained a ‘safety valve’ – that is, public property on which students could organise with First Amendment protection.

But, as the 1964 Fall semester began, something snapped. Heads of political organisations returned from their summer break – many working with civil-rights organisations in the South – to find a notice from the dean of students, Kathryn Towle, informing them that Bancroft and Telegraph was, in fact, university property and would now be subject to the same rules and restrictions as everywhere else on campus. This meant no tables, no speeches, no fundraising – no safety valve.

In a matter of days a political phenomenon was born. And after months of suspensions, negotiations, sit-ins, arrests and strikes, a coalition of student groups, calling itself the Free Speech Movement, prevailed. The students were free to organise on campus, as well as off. The in loco parentis responsibilities of the university were lifted. Student politics as we know it today was born.

This month, the Free Speech Movement celebrates its fiftieth anniversary and the inevitable waves of nostalgia and hagiography that this has unleashed have got some people’s backs up. An adoring biography of Mario Savio, the charismatic 22-year-old leader of FSM, is required reading for all students at Berkeley this semester. A string of events, including a ‘hootenanny’, are planned across the city. Savio’s son is even directing a musical about FSM.

Writing in the Wall Street Journal, a Berkeley veteran mourns this outpouring of ‘FSM kitsch’. Not only does it turn the whole affair into a symbol of twee leftism, he fumes, but it obscures the fact that the FSM’s legacy has been far from liberal. The ‘New Left’ FSMers have formed the current vanguard of ‘radical professors [who] insist on ideological conformity and don’t take kindly to dissent by conservative students’, he writes.

You can understand the desire to burst the bubble. For greying lefties on both sides of the Atlantic, Berkeley in the Sixties is a perennial ‘happy place’ – a refuge of certainty, purpose and mission in these politically disoriented times. And, indeed, campus ‘speech codes’, equality policies and bans have infected Anglo-American universities since the Eighties, working to censor dissent and impress upon students the sort of liberal-left orthodoxies that FSM members held dear. So, have the heirs of FSM become the campus Thought Police of today?

Cynicism isn’t the antidote to nostalgia. To tar the FSM as the direct hippy-tinged forebears to the new faux-left authoritarianism only obscures the importance and impact of those fateful few months, and risks explaining away the political contortions that have taken place since. Given the parlous state of campus free speech at the moment, there is plenty that students today could learn from the FSM.

From the early days of the Berkeley protests, students refused to be cowed. After Dean Towle had handed down her edict, student groups, including the DuBois club and civil-rights group Slate, formed a coalition called United Front and continued to set up their tables. On 30 September eight students – mainly selected from the leadership of disobedient student organisations – were cited for violating university rules and summoned by campus officials. At the arranged 3pm meeting, 300 students showed up – insisting they were just as culpable as their leaders. After sitting outside Dean Williams’ office until the early hours, it was announced that the eight students had been suspended indefinitely.

But it was the arrest of one graduate, Jack Weinberg, that became the lightning rod for all that would follow. On 1 October, Weinberg was manning a table for the civil-rights group Congress on Racial Equality (CORE) when he was approached by a campus policeman. He refused to leave the table and was arrested, but before they could drive off campus, hundreds of students spontaneously surrounded the police car. They stayed there for 36 hours. While United Front leaders and sympathetic faculty negotiated for Weinberg’s release, he ate sandwiches, urinated in Coca-Cola bottles and listened to the speeches that were being given from the roof of the police car. The most charismatic speaker was Mario Savio, a 22-year-old Catholic boy from Queens, New York. After the sit-in was over, Savio emerged as the spokesman for a student coalition that was now calling itself the Free Speech Movement.

The instant solidarity felt between the different student groups quickly cemented the movement. But was it just lefty self-interest, as some revisionists would have it? Talking to Steve Weissman, then a graduate student in the history department who led the Graduate Coordinating Committee of FSM, it becomes clear that a genuine belief in freedom of speech bound the activists together.

‘There was a broad belief in freedom of speech among the students’, he says, talking to me from his home in France. Indeed, Weissman, like many of the students then, seemed to think their demand for free speech was a no-brainer: ‘We just expected that we should have the same rights on campus that we had off campus, and the university shouldn’t play parent… It was not a terribly radical programme!’

It was this foundational commitment to free speech for all that gave the FSM its strength. While the majority of the students in the coalition were civil-rights activists and leftists of varying hue, it was an inclusive movement. Even Students for Goldwater, a group which supported Republican presidential candidate, Barry Goldwater – a reactionary right-winger who opposed the 1964 Civil Rights Act – was given the same representation and voting rights in the FSM’s various committees.

‘It was one of the great strengths of the Free Speech Movement’, says Bettina Aptheker, an FSM leader and now a professor of feminist studies at the University of California, Santa Cruz. ‘The only requirement was that they believed in the First Amendment – freedom of speech. That was it; we didn’t care what their politics were.’

Of course, this diversity didn’t come through in the damning media coverage, which painted the protesters as the Red Scare incarnate. Then a member of the Communist Party, Aptheker jokes that the tarring FSM received from the media cemented her role in the movement. ‘We held a rally after we released the police car, and Mario suggested I speak as the one member of the Free Speech Movement who actually was a Communist!’

After months of fraught negotiations, rallies and sit-ins, the university offered a ‘compromise’. All restrictions on political advocacy would be lifted, aside from those which ‘directly result’ in ‘unlawful acts’. It was a clear attempt to split the student coalition between the respectable, party-political groups and the civil-rights and leftist groups for whom civil disobedience was their bread and butter. The FSM was having none of it.

The students stepped up their efforts with two mass sit-ins in the Sproul Hall academic building – fittingly, the building was named after Robert Gordon Sproul, the Berkeley chancellor who imposed a ban on all political and religious meetings on campus in 1934.

The first sit-in attracted 300 students, the second attracted 800, including folk singer Joan Baez, who led the students into the building to the tune of ‘We Shall Overcome’. The second sit-in also played host to Savio’s most stirring and famous speech. Voice cracking and infuriated, he said:

‘There’s a time when the operation of the machine becomes so odious, makes you so sick at heart, that you can’t take part! You can’t even passively take part! And you’ve got to put your bodies upon the gears and upon the wheels… upon the levers, upon all the apparatus, and you’ve got to make it stop! And you’ve got to indicate to the people who run it, to the people who own it, that unless you’re free, the machine will be prevented from working at all!’

Weissman shares a story that points out the disparity between these two moments, both etched in our Sixties cultural memory. While the FSM has gone down in history as a triumph of peaceful protest, that, he tells me, is not the full story. ‘When Mario did that brilliant speech about throwing your body on the gears, it was full of existential angst… because we weren’t Ghandians; for us non-violence was a tactical choice. When Joan Baez was going to come down and sing at the demonstration, we got a call from her non-violent guru. He said “can you commit to being non-violent?”. And I said “No”.’

During the second sit-in on 3 December, police were called and hundreds of students were arrested over a period of 12 hours. Locked out of the building and stirred by this latest escalation, the faculty met and called on university management to issue an amnesty for students and complete, unrestricted advocacy. The faculty then called a strike, forcing the Academic Senate to meet and consider the FSM’s proposal. ‘That’s what really swung it’, says Weissman, who led the call for the strike.

On 8 December, the Academic Senate voted 824 to 115 in favour of the motion ‘That the content of speech or advocacy… should not be restricted at the university’ other than ‘to prevent interference with the usual functions of the university’. Essentially, it was the FSM’s position.

This moment laid the groundwork for much of the student activism that was to follow, specifically the movement against the Vietnam War. ‘The main achievement of the FSM was that it opened up campus for the anti-war movement. I think that was absolutely essential’, says Weissman.

More broadly, this victory instilled the idea in students across the US that open debate was a prerequisite of any progressive movement. ‘Freedom of speech is a central principle; then, you organise’, says Aptheker.

How things have changed. The image of students and faculty coming out together to defend free speech for all seems like a distant dream in a time in which both sides seem to be calling for debate and discussion to be reined in. In May this year, the former US secretary of state, Condoleezza Rice, backed out of speaking at Rutgers University in New Jersey after students protested against her invitation. This new censoriousness among students is something that concerns Aptheker: ‘I think it’s wrongheaded that young people think it’s okay to ban speakers. It’s a very slippery slope, and once you set the precedent then it’s going to come back and bite you in the tuckus!’

Similarly, in a recent email to staff and faculty, commemorating the Free Speech Movement, Nicholas Dirks, the current chancellor of UC, Berkeley, made the sad state of campus free speech all the more clear. ‘We can only exercise our right to free speech insofar as we feel safe and respected in doing so’, Dirks wrote, insisting that free speech should be tempered by ‘civility’. I ask Aptheker if the Free Speech Movement would have achieved all it did if the students had been terribly civil. ‘No!’, is her forthright response. ‘Civil speech became a watchword that’s been used all over the country by various administrations as a way of chilling freedom of speech.’

In response to the email, Aptheker and a number of FSM veterans wrote an open letter to Dirks, thanking him for his support of FSM but warning him about the potential impact of his insistence on ‘civility’. In closing, they quote the lyrics to a song, performed by then Berkeley student Malvina Reynolds in Sproul Plaza, 1964:

‘It isn’t nice to block the doorway. It isn’t nice to go to jail.

There are nicer ways to do it, but the nice ways always fail.

It isn’t nice, it isn’t nice,

You told us once. You told us twice.

But if that is freedom’s price, we don’t mind.’

In a time in which both students and university administrators are hell-bent on limiting free speech, protecting their supposedly delicate peers from the offensive, upsetting or corrupting words of others, this lyric should be required reading.

Tom Slater is assistant editor at spiked and coordinator of the ‘Down With Campus Censorship!’ campaign. Find out how you can get involved here.

Who funds spiked? You do

We are funded by you. And in this era of cancel culture and advertiser boycotts, we rely on your donations more than ever. Seventy per cent of our revenue comes from our readers’ donations – the vast majority giving just £5 per month. If you make a regular donation – of £5 a month or £50 a year – you can become a and enjoy:

–Ad-free reading

–Exclusive events

–Access to our comments section

It’s the best way to keep spiked going – and growing. Thank you!

Comments

Want to join the conversation?

Only spiked supporters and patrons, who donate regularly to us, can comment on our articles.