Finding Fela: rhythm and revolution

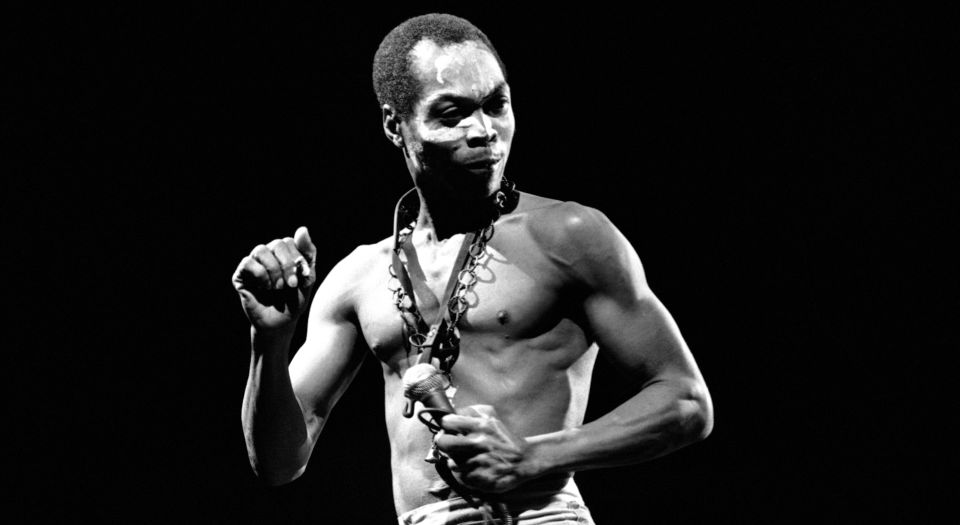

Fela Kuti was that rarest of things: a bona fide, fists-in-the-air pop rebel.

Want to read spiked ad-free? Become a spiked supporter.

In the opening minutes of Finding Fela, Alex Gibney’s docu-love-letter to the Nigerian musical revolutionary, Fela Kuti, there is a particularly incisive moment. In a rush of emphatic talking heads, waxing lyrical about the hypnotic Afrobeat genre Fela helped create, his rabble-rousing protests against Nigeria’s military dictatorship, and his fizzing, indefatigable showmanship, up pops Paul McCartney. Dye-job hair glistening – looking, as he does, like a ‘young for her age’ grandmother – our Paul talks about when he first saw Fela and his band, the Africa 70, perform in Lagos: ‘It was a little scary… we were the only white guys there.’ Then, when the performance began, he burst into tears.

It’s in this moment you realise that Fela Kuti was everything his Western contemporaries weren’t. Unlike effusive, effete rock stars like McCartney, who would later shed yet more metaphorical tears over Africa with Live Aid, Fela was a two-fists-in-the-air force to be reckoned with.

The end of McCartney’s story, which is sadly omitted here, is that, having gotten wind the former Beatle was looking to scout African musicians to record Band On The Run, Kuti denounced him from the stage. Later on, he even showed up unannounced at the studio McCartney was using in Lagos and accused him of ‘stealing black man’s music’.

It was this uncompromising personality, willingness to speak his mind and cocksure resolve that made Fela Kuti one of the few pop stars we could stretch to call political.

Drawing on archive footage of Kuti’s legendary performances, candid interviews with the man himself and the reflections of his friends, family and admirers, Gibney tracks Kuti’s development from the respectable, middle-class son of well-respected politicos to jumpsuit-clad reprobate and thorn in the establishment’s side.

He left Nigeria for England at the age of 17 to study medicine, but instead ended up at the Royal College of Music. Travelling back and forth from England, America and Nigeria, he soaked up jazz and soul, and fused it with Ghanaian highlife music to form Afrobeat, a hypnotic, pulsating new form of dance music that would become the backdrop for his vociferous attacks on the Nigerian establishment.

The shy and straight-laced Fela mixed with musicians, Black Panthers and Pan-Africanists, developing a legendary libido, a penchant for cigar-sized joints and a perspective on African oppression that suffused his music. No longer singing lightweight songs about his soup in his native Yoruba, as Sandra Izsadore, an American singer, activist and one of the proud polygamist’s dozens of wives, hilariously points out, he started singing in Pidgin English, and soon became a troot-talking icon for Anglophone Africa.

His Friday night ‘Yabis’ sessions at his club the Shrine, down the road from his commune-cum-compound Kalakuta, were the stuff of legend. Dancing girls, African ceremony, 40-minute songs and cutting sloganeering about the parlous state of Nigerian society drew the residents of Lagos out in their droves.

It wasn’t long before the authorities became suspicious. Kuti was arrested, jailed, flogged and beaten time after time. But this only toughened his resolve, and prompted him to pen fiery tunes like ‘Alagbon Close’, named after the infamous Lagos prison he was thrown in on trumped-up charges. Despite the clampdown, his popularity and ubiquity in the slum soundsystems of Nigeria and beyond only grew.

However, it all culminated in tragedy four years later when Kalakuta was raided by the army. It was almost burnt to the ground, his wives were beaten and raped, and his mother, Funmilayo, was thrown from a second-floor window, later dying of her injuries. Fela delivered a coffin to the authorities in protest and fired back with one of his most heartfelt hits, ‘Unknown Soldier’. This sparked a succession of some of his most irreverent and best-loved songs including ‘Zombie’, a send-up of the unfeeling, goose-stepping cronies who enforced General Olusegun Obasanjo’s brutal junta.

Gibney’s style is strangely staid, and he often slips into effusive, banal hagiography. But as with the director’s acclaimed portrait of disgraced cyclist Lance Armstrong, The Armstrong Lie, he retains a disarming ambivalence. Gibney follows the production of Fela!, a hit Broadway musical about Kuti helmed by Bill T Jones. While the show itself looks like a lightweight and superficial romp through Fela’s life and songbook, the scenes in which Jones and his crew workshop the show tease out some of the more troubling sides of Kuti, including his chauvinism, his mistreatment of his family and, in the end, the lightweight content of his political views. As various talking heads attest, Fela’s politics became increasingly mired in backwards African spiritualism and hippy-ish black-power utopianism.

As frustrated, unpaid musicians and acolytes left his side, he developed an increasingly dodgy entourage, including a Ghanaian magician and fraudster called Professor Hindu who became Kuti’s spiritual guide. He died in 1997 of AIDS-related complications, shunning ‘Western’ treatment and continuing to have unprotected sex with his remaining wives. His supposed ‘revolutionary vision’ for Africa was as incomprehensible and out-of-reach as ever. Millions of Nigerians brought Lagos to a standstill as they turned out to pay their respects, but, of course, this never cohered into anything truly earth-moving in Nigeria.

Fela Kuti was, in the end, an enduring, exhilarating, international pop icon. Today, Afrobeat is not just the preserve of greying world-music fans with pony tails, but continues to influence a new generation of hip musicians, from King Krule to Tune-Yards. And his legend in Africa as a musician and man of the people is sacrosanct. Above and beyond his revolutionary pretensions, this is his rightful legacy. But there’s something about his own brand of pop and politics that marks Kuti out as different.

While Bob Geldof and Co were screaming ‘feed the world’, stepping in with guitars and smug faces to save the poor Africans, Fela preached autonomy, self-determination and the might of the masses. His rebellion against the Nigerian authorities was, unavoidably, shallow, fuelled by his ‘alternative’ lifestyle and his rock-star egotism. But the Sex Pistols, cruising down the Thames and chugging out ‘God Save the Queen’, probably didn’t even make Liz blink, let alone send the boys round.

Finding Fela pays tribute to a man who was, if not a revolutionary, a genuine rebel. As Fela’s son, Femi, warmly reflects: ‘You were always wondering what trouble he was going to cause next.’ This is the sort of attitude pop music is sorely lacking.

Tom Slater is assistant editor at spiked. Follow him on Twitter: @Tom_Slater_

Watch the trailer for Finding Fela:

Picture by: PA

Who funds spiked? You do

We are funded by you. And in this era of cancel culture and advertiser boycotts, we rely on your donations more than ever. Seventy per cent of our revenue comes from our readers’ donations – the vast majority giving just £5 per month. If you make a regular donation – of £5 a month or £50 a year – you can become a and enjoy:

–Ad-free reading

–Exclusive events

–Access to our comments section

It’s the best way to keep spiked going – and growing. Thank you!

Comments

Want to join the conversation?

Only spiked supporters and patrons, who donate regularly to us, can comment on our articles.