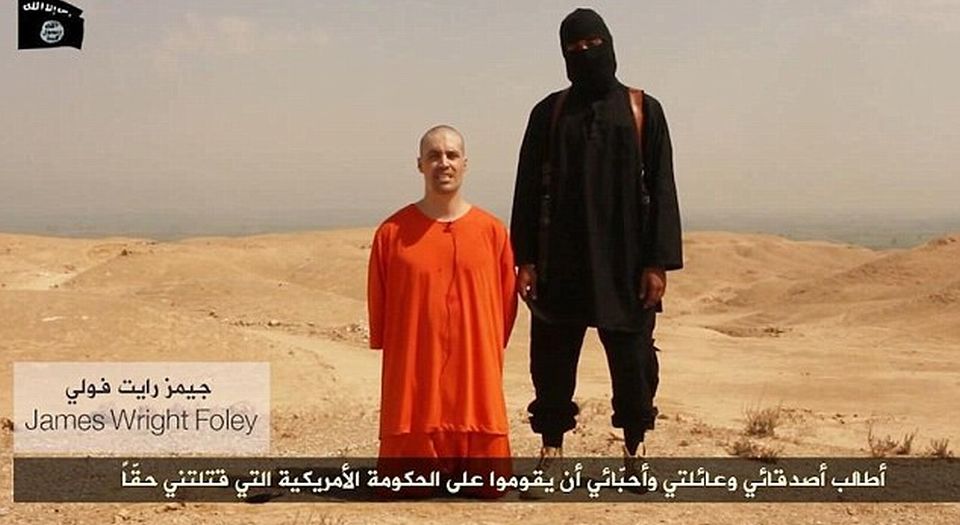

This gruesome video contains a message to Britain, too

What that barbaric beheading tells us about a crisis of Britishness.

Want to read spiked ad-free? Become a spiked supporter.

Clad in black, with a mask hiding his face, the jihadist speaks to the camera with an unmistakable London accent. As he mercilessly beheads his victim – the American journalist James Wright Foley – it is difficult to avoid the conclusion that this individual’s barbarism threatens the landscape of England, too, the place from which he presumably hails. His ISIS-produced video, calculated to provoke the maximum amount of terror, is titled ‘A Message to America’. But everyone watching this morbid performance of inhumanity surely understands that this theatre of fear also represents ‘A Message to Britain’.

It is becoming increasingly common to see jihadists of the Islamic State of Iraq and the Levant (ISIS) boastfully communicate their threats to the world in British accents. Earlier this week, an ISIS video posted on YouTube showed a Japanese prisoner also being interrogated by jihadists speaking in British accents.

It is unlikely that there exists a vast army of young British jihadists ready to perform acts of barbaric violence for the cameras. But you don’t need thousands of willing executioners in order to cultivate a climate of insecurity and terror. Following the horrific stabbing to death of a young British soldier on the streets of Woolwich in London last year, it has been clear that such imagery and threats of inhuman acts can prey on the imagination of the public.

Earlier this week, the UK prime minister David Cameron said Britain needs to fight the ‘monstrous’ ISIS militants promoting havoc in Iraq in order to prevent them from causing ‘mayhem on our own streets’. That there is a connection between the unravelling of the Middle East and developments here in the UK should be in no doubt. But the important point to grasp is that the phenomenon of the British jihadist is not simply a reaction to events in Syria or Iraq – it is above all an outcome of, for want of a clearer phrase, the crisis of Britishness at home.

The answer to the question ‘What does it mean to be British?’ has in recent years proved very elusive. Nevertheless, this question continually haunts public life in Britain. Politicians are aware of this problem and periodically try to engage with it. Former Labour PM Tony Blair sought to outline what are the main British values, only to discover that he was not up to the task. His government wanted to launch a British Day, but it later quietly abandoned the project. His successor, Gordon Brown, was equally unable to give meaning to ‘the British way of life’. The humiliating failure of Brown’s government to produce a ‘statement of British values’ really showed that the meaning of Britishness could no longer be taken for granted.

Recently, Cameron announced that ‘Britishness’ will be taught in schools. Tristram Hunt, Labour’s shadow secretary for education, agreed with this idea and argued that it is possible to ‘generate a sense of national understanding’ through the teaching of such subjects as history, citizenship and religious education. Possibly. But in the first instance there needs to be clarity about the content of what will be taught. And that clarity is conspicuous by its absence in British life today.

The British establishment has failed to provide society with any sense of national purpose. Any attempt to celebrate Britishness or advocate patriotic themes tends to be carried out with more than a hint of defensiveness and embarrassment. The political elites carefully avoid coming across as having any strong convictions about their Britishness. Their lack of conviction is most strikingly expressed through their virtual silence on the current debate about the future of the Union. None of the leaders of the main Westminster parties seems prepared to join the battle of ideas over Scotland’s future. Instead they outsource the campaign to defend the United Kingdom to retired parliamentarians and marginal political figures with little to lose.

When the ‘British way of life’ has such little meaning to those who run and manage society, is it any surprise that it does little to inspire loyalty or identification among Britain’s minority populations? Usually, the elites’ failure to provide young people with meaning simply leads to a reaction of apathy and to feelings of detachment from mainstream society. But more recently, in some cases, this reaction has turned into a more radical and active search for a sense of attachment, one that might really provide people with meaning and value. The influence of a jihadist youth culture over a small section of Britain’s Muslim youth is one outcome of this new quest for alternative sources of meaning.

In British society, the appeal of the jihadist youth culture represents the crystallisation of, first, a sense of detachment from the cultural values of Western society, and secondly an open rejection of those values. What often looks like a sudden conversion to radical Islam by an impetuous or confused young man is actually usually preceded by the detachment of that individual from a way of life that has failed to provide him with any purpose. Sometimes, this conversion mutates into an intense hatred of the West, and in a few cases it can lead people towards an ISIS training camp in Syria.

It is important that we don’t become disoriented by the spectacle of terror in this videoed beheading of an American journalist. A sadistic act of murder is just that. It does not represent an existential threat to civilised life. The threat represented by a small number of callous British jihadists is insignificant compared with the danger of losing the battle for hearts and minds at home. At present, the battle for the British way of life is being conducted at the level of rhetoric alone. It is a battle that is too important to leave to the risk-averse culture of the British establishment. The lesson of recent years is surely that decent, democratic, meaningful values cannot be taught unless they are also lived.

Frank Furedi is a sociologist and commentator. His latest book, First World War: Still No End in Sight, is published by Bloomsbury. (Order this book from Amazon (UK).)

Picture: YouTube

Who funds spiked? You do

We are funded by you. And in this era of cancel culture and advertiser boycotts, we rely on your donations more than ever. Seventy per cent of our revenue comes from our readers’ donations – the vast majority giving just £5 per month. If you make a regular donation – of £5 a month or £50 a year – you can become a and enjoy:

–Ad-free reading

–Exclusive events

–Access to our comments section

It’s the best way to keep spiked going – and growing. Thank you!

Comments

Want to join the conversation?

Only spiked supporters and patrons, who donate regularly to us, can comment on our articles.