The truth behind the stay-at-home generation

It’s not the economy keeping young-ish people in the family home.

Want to read spiked ad-free? Become a spiked supporter.

This week, Generation Y(-me!?) were given yet another reason to feel sorry for themselves. According to data from the Office for National Statistics (ONS), the number of 20- to 34-year-old Brits living at home with their parents has risen to a staggering 3.3million – an increase of a quarter since records began in 1996. ‘A further a sign of how the economic downturn has hit young people’, claimed one article in the Financial Times; a Guardian scribe lamented the fate of these pitiable ‘victims of rising house prices [and] a difficult job market’.

At first, it’s hard not to have sympathy for the so-called stay-at-home generation. The odds certainly appear stacked against them. Unemployment is at its highest among young people. More and more graduates leave university with degrees that count for little in the job market and are saddled with hefty debts for their trouble.

However, the fact of the matter is that while this certainly makes finally packing up your Meccano set and heading out on your own a bit harder – and perhaps more daunting – it most certainly doesn’t make it impossible. Another look at the figures and it becomes clear that there are plenty of young people who feasibly could move out and choose not to.

Staggeringly, of those twentysomethings still ensconced in their teenage bedrooms, only 13 per cent of them are unemployed. What’s more, contrary to all the brow-furrowing over malevolent zero-hours contracts and the scarceness of full-time employment, further statistics from the ONS state that of the roughly 30million people in work in the UK, barely a third work part-time.

The failings of the labour market are clear, but they come nowhere near to explaining away this phenomenon. Similarly, rents have undoubtedly been soaring – rising to a monthly average of £1,126 in London. But, believe it or not, there are places even poorly paid Londoners can afford – although it might *gasp* mean breaking out into the sprawling netherworld that lies beyond Zone 2.

The spike in young people staying and moving back home, although undoubtedly exacerbated by the floundering economy, nevertheless marks a profound cultural shift in the attitudes of young people towards independence. And it doesn’t take much digging to grasp the roots of it all.

The value of adulthood is battered out of young people nowadays. When last year psychologists announced they were extending the clinical definition of adolescence to 25, it felt sadly appropriate. Indeed, in all corners of society, young people are being fretted over and micromanaged with all manner of initiatives to help them negotiate the adult world. From university wellbeing services to the recent attempts of one charity to rebrand youth joblessness as a mental-health crisis, young people are imbibing the idea that they are essentially overgrown children in need of constant support and intervention.

The sense of victimhood is bolstered by the ‘jilted generation’ brigade, who insist that young people have been undone by the avarice of their baby-boomer forbears. As a result, so we’re told, young people will never be able to achieve the same success their parents’ generation enjoyed. Moving out into less-than-lush surroundings has come to be seen as a kind of concession to the oldies wot wronged us. The bizarre focus on house prices in this discussion is particularly revealing on this point. Young people have been led to believe that their parents skipped renting and started buying up houses when they were barely out of school – an idea which Grace Dent gave a thorough rinsing in the Independent this week. In this sense, Generation Y have begun to conceive of themselves as the victims of an illusory, more prosperous past, to the point where even renting a box-room in a mould-ridden house-share is an inconvenience they’re not prepared to endure.

With all of this in mind, you can almost see why they choose to stay at home and spend their disposable income on other things. If things are indeed so bleak, why not buy a car or, as is increasingly becoming the norm, save up your wages and go travelling? Young people seem to forget having your own wheels or jetting off around the world are luxuries that were never within the grasp of their supposedly cash-rich parents.

At the end of last year, Kristian Niemietz of the Institute of Economic Affairs pointed out that the cost of housing has not only increased at a faster rate than earnings, but also at a faster rate than the cost of almost everything else. This, Niemietz suggests, confirms that the stay-at-home generation is an economic rather than cultural phenomenon, which has shifted leaving home down the list of young people’s priorities. ‘They do want to move out early – but not at any cost’, he writes. In essence, Niemietz is right. For young people today, independence often comes a distant second to some extra cash for a few more nights out a month or the chance to pay to volunteer for the summer at some Cambodian parakeet reserve.

But independence is far more important than that. Only by taking that terrifying and liberating step of heading out on your own in life do people gain any genuine sense of moral autonomy. For previous generations, diving in, muddling through, living in hovels, and sustaining yourself purely on beans and white cider were how young people learned to negotiate the adult world. Some people in my generation have simply internalised the idea that this is somehow beyond them, or worse, beneath them.

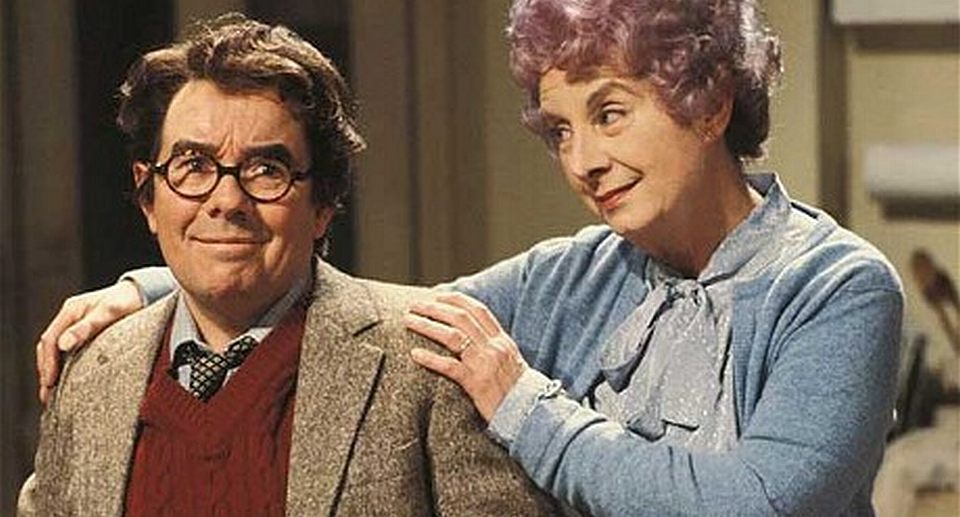

This is tragic. Who wants to look back on their twenties as a time full of having to watch Poirot with mum, or shushing your one-night stands because dad’s got to be up early? Like I said, some things are more important.

Tom Slater is assistant editor at spiked.

Who funds spiked? You do

We are funded by you. And in this era of cancel culture and advertiser boycotts, we rely on your donations more than ever. Seventy per cent of our revenue comes from our readers’ donations – the vast majority giving just £5 per month. If you make a regular donation – of £5 a month or £50 a year – you can become a and enjoy:

–Ad-free reading

–Exclusive events

–Access to our comments section

It’s the best way to keep spiked going – and growing. Thank you!

Comments

Want to join the conversation?

Only spiked supporters and patrons, who donate regularly to us, can comment on our articles.