The Gettysburg Address: a great work of humanity

150 years on, Lincoln’s words retain their democratic power.

Want to read spiked ad-free? Become a spiked supporter.

‘Fourscore and seven years ago our fathers brought forth upon this continent a new nation, conceived in Liberty, and dedicated to the proposition that all men are created equal.’

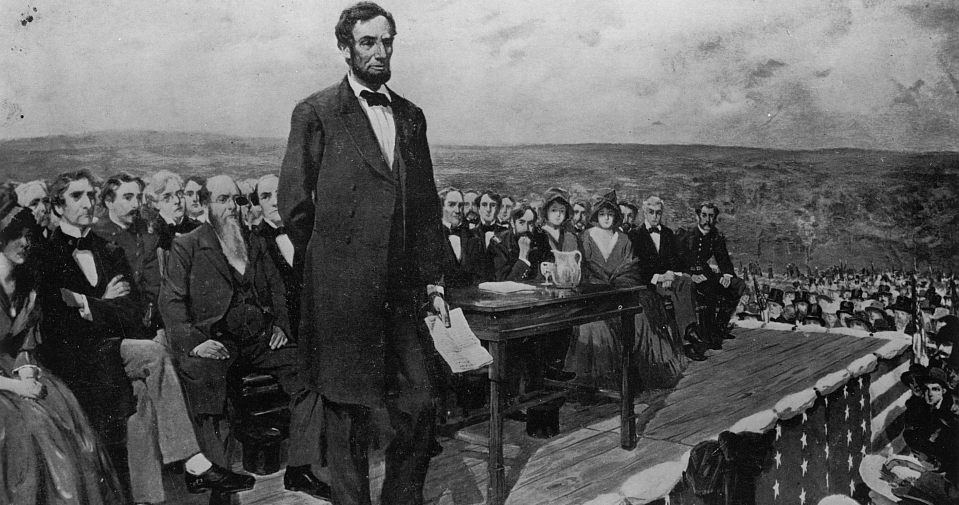

The ground groaned and burped up dead limbs at Gettysburg as President Lincoln gave his address over the bodies of the men who had lost their lives in that most terrible battle of the American Civil War. Though the war still raged, the speech already set the tone for its end. Lincoln’s words soared, tying the founding of the United States to its rebirth as a nation free of slaves. Before him, Edward Everett had given a long speech in the classical style, full of rhetorical flourishes. Lincoln’s three paragraphs, in the plain words that any man who read the Bible could understand, fit on a printed page. Less than two years later, Lincoln himself would be assassinated. And yet his words caught the mood then, and have since become a near sacred text of American democracy.

The war between 1861 and 1865 tested the Union to destruction. Three quarters of a million Americans died – more than in the Second World War – out of a population of just over 30million. As the address claims, the troops died fighting over the question of liberty: that government of the people by the people for the people shall not perish from the Earth.

The United States was a beacon of liberty across the world when it was founded in 1776. Democrats everywhere celebrated the victory of the new republic against George III. But the slave plantations of the southern states were a terrible stain on that democracy. Lincoln’s refusal to allow the slave-owning classes to expand into the western states caused the South to rebel. Breaking up the Union was their way of defending the ‘peculiar institution’ of slavery. It was held against Lincoln that he fought in the first instance not to abolish slavery, but to defend the Union. Looking back, he was right.

The threat of the Southern secession was real. Southerners saw the chance of a great empire of slavery extending from Cuba, retaking the Black Republic of Haiti, to join up with the South. Those liars in Europe, Louis Napoleon and Lord Palmerston, having used slavery as an excuse for their hostility to the United States, were on the verge of joining the South. Britain even sent troops to Canada in preparation for war against the Union.

The Civil War was industrial, running on railway lines, and furnished by great munitions factories and shipyards. The early rebel victories came easy to those American cavaliers who did not work for themselves and were disproportionately represented in the Union’s armed forces. Over time, though, the industrial superiority of the North began to tell. Millions of men were sent across the country by rail. It was a pitiless war stoked with fresh recruits.

Lincoln’s address appeals to liberty, and to democracy. It does not even mention slavery, except in the negative: ‘All men are created equal.’ The work of reconstruction would be a harsh test of the country’s ability to free itself of white supremacy. The speech does not just point to the future, but just as importantly it means to heal the terrible divisions of the war, by honouring the men who fought on both sides.

For that it is a great work of humanity. It honours the dead as well as hoping that their deaths will not be in vain, but that the republic will persist.

James Heartfield’s British Workers & the US Civil War is published by Reverspective.

Who funds spiked? You do

We are funded by you. And in this era of cancel culture and advertiser boycotts, we rely on your donations more than ever. Seventy per cent of our revenue comes from our readers’ donations – the vast majority giving just £5 per month. If you make a regular donation – of £5 a month or £50 a year – you can become a and enjoy:

–Ad-free reading

–Exclusive events

–Access to our comments section

It’s the best way to keep spiked going – and growing. Thank you!

Comments

Want to join the conversation?

Only spiked supporters and patrons, who donate regularly to us, can comment on our articles.