Cutting a pound of flesh from Shakespeare

Rewriting The Merchant of Venice to ‘tackle its anti-Semitism’ is a very foolish endeavour.

One of the most unattractive features of Western society today is its obsessive presentism – that is, its estrangement from both the past and the future and its myopic focus on the here-and-now. Twenty-first-century culture continually seeks to erode the line that separates the present from the past. Past events – whether historical or literary – are now evaluated from the viewpoint and values of today. This culturally anachronistic approach means that centuries-old historical figures and literary characters are often castigated for their racism, sexism, classism or any other trait that offends the imagination of contemporary readers.

One of the worst aspects of this cultural necrophilia is the trend for rewriting the great literature of the past. Yesterday, it was reported that poor old William Shakespeare has been brought into the frame – apparently the British author Howard Jacobson plans to rewrite The Merchant of Venice in order to ‘tackle its anti-Semitism’. I have the greatest of respect for Jacobson, so these reports sadden me.

No doubt Jacobson has the best of intentions, but the fact is that rewriting a Shakespeare play – especially one as controversial as The Merchant of Venice – is a form of rewriting history. Such an endeavour threatens to violate the integrity of art, and it encourages the politicisation of aesthetic judgment.

Does The Merchant of Venice have disturbing anti-Semitic overtones? Yes, it does. Does its character of Shylock personify the caricatured depraved and greedy Jewish antichrist? Yes – there’s no doubt Shylock will repel audiences unsympathetic to the Jews. But this play was written in the sixteenth century, and it was an attempt to capture the sensibility and moral standards of that era. In a world where Jews were regarded as an alien threat to Europe’s moral order, Shakespeare’s depiction of Shylock was unexceptional. Just as Greek tragedies did not preach messages about abolishing slavery, so sixteenth-century European writers did not promote multiculturalism.

What is most remarkable about The Merchant of Venice is that Shylock, despite being a moneylender seeking a pound of flesh from his victim, actually comes across as an ambiguous and possibly even sympathetic character. He is not one-dimensionally malevolent; he is a complex individual. He’s not just a despicable Jew but also a human being. Indeed, the questions asked by Shylock in Scene 1 of Act 3 touch profoundly upon what it means to be human; and, whatever Shakespeare’s intentions, here the play manages, at least momentarily, to transcend the prejudices of the era.

‘Hath not a Jew eyes? Hath not a Jew hands, organs, dimensions, senses, affections, passions; fed with the same food, hurt with the same weapons, subject to the same diseases, heal’d by the same means, warm’d and cool’d by the same winter and summer as a Christian is? If you prick us, do we not bleed? If you tickle us, do we not laugh? If you poison us, do we not die? And if you wrong us, shall we not revenge? If we are like you in the rest, we will resemble you in that. If a Jew wrong a Christian, what is his humility? Revenge. If a Christian wrong a Jew, what should his sufferance be by Christian example? Why, revenge. The villainy you teach me, I will execute, and it shall go hard but I will better the instruction.’

Does Shylock need to be rehabilitated and reinterpreted by modern authors? Not really. Rather, his predicament needs to be understood. Like all great characters in powerful dramas, he can be interpreted in a variety of ways. That is what we should expect from genuine art. Yes, the play also raises some disturbing questions about the representation of Jews, and of course a twenty-first-century audience can discuss that in an intelligent manner.

Modernising The Merchant of Venice is likely to generate political propaganda rather than art. We do not need Shakespeare to be sanitised and recast as a twenty-first-century right-on writer.

The real issue here is not the dramatic representation of Jews; it is the plundering of the past. It is worth noting that the publisher of the new Merchant of Venice – Penguin Random House – has commissioned other authors to rewrite various Shakespeare plays. Margaret Atwood will rewrite The Tempest; Jeanette Winterson will have a go at The Winter’s Tale; Anne Tyler will do the business on The Taming of the Shrew. It’s a pity that these talented writers have been assigned the task of cannibalising great sixteenth- and seventeenth-century plays. But one way or another, Shakespeare will survive what Penguin Random House describes as an ‘exciting opportunity to reinvent these seminal works of English literature’. Reinventing seminal works – why?

Postscript: It turns out the news reports about Howard Jacobson planning to do a ‘clean-up’ of The Merchant of Venice were misguided. Howard has got in touch with me to say this is not accurate. He also says he shares my distaste for our modern habit of plundering the past, but makes the very good point that in the realm of literature dipping into past stories and reimagining them for contemporary audiences has long been an interesting and fruitful endeavour. I’m happy to put the record straight. It will of course be fascinating to see how Howard interprets The Merchant of Venice.

Frank Furedi‘s new book, Authority: A Sociological History, will be published by Cambridge University Press later this month. (Order this book from Amazon (UK).) Visit his website here.

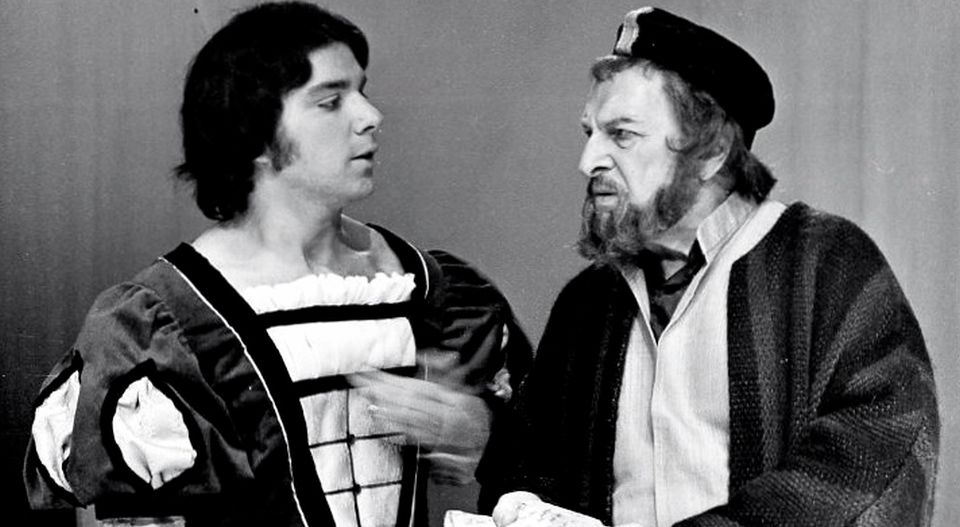

Picture: Alan Safier (Gratiano) and Morris Carnovsky (Shylock) in The Merchant of Venice in 1973 via Wikimedia Commons.

To enquire about republishing spiked’s content, a right to reply or to request a correction, please contact the managing editor, Viv Regan.

Comments

Want to join the conversation?

Only spiked supporters and patrons, who donate regularly to us, can comment on our articles.