Should the mentally disabled have sex?

Having judges rule on certain people's sex lives has ugly echoes of the past.

Want to read spiked ad-free? Become a spiked supporter.

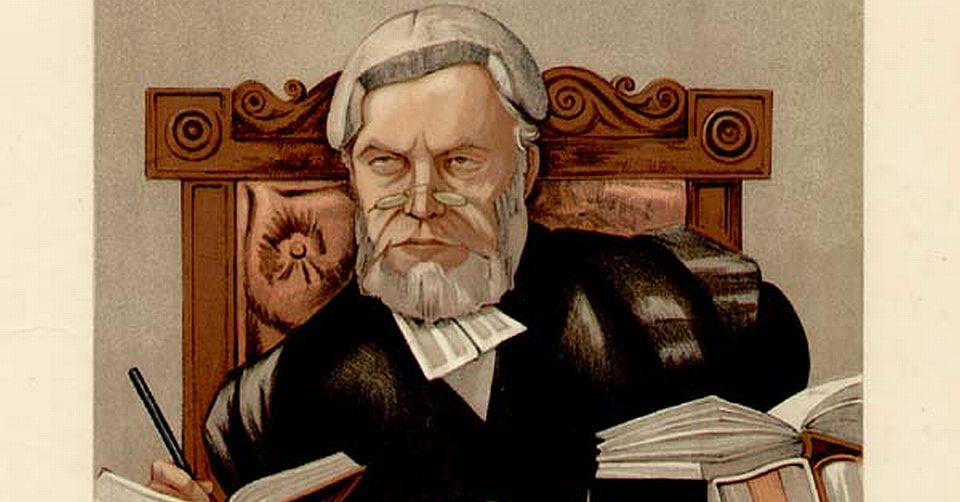

In 1927, in the case of Buck v Bell, the US Supreme Court upheld a 1924 state law in Virginia permitting the compulsory sterilisation of mentally retarded persons on eugenic grounds. Carrie Buck was said to be one of three generations of ‘feeble-minded’ and ‘promiscuous’ women. In the course of a landmark judgment, Justice Oliver Wendell Holmes wrote:

‘We have seen more than once that the public welfare may call upon the best citizens for their lives. It would be strange if it could not call upon those who already sap the strength of the state for these lesser sacrifices, often not felt to be such by those concerned, to prevent our being swamped with incompetence. It is better for all the world, if instead of waiting to execute degenerate offspring for crime, or to let them starve for their imbecility, society can prevent those who are manifestly unfit from continuing their kind… Three generations of imbeciles are enough.’

If a judge made such observations today, there would be uproar. But at the time, the American authorities espoused a theory of ‘negative eugenics’, which rested on the assumption that the state should take positive measures to prevent society being burdened by those seen as degenerate. That theory fell out of favour in the 1940s, though Buck v Bell was never formally overruled.

By contrast, the British state was more receptive to positive eugenics, which urged the great and the good to reproduce more people themselves. This theory relied on moral suasion, and an expectation that processes of natural selection would eliminate those deemed weak and unfit.

It’s ironic, therefore, to see a recent decision from the UK Court of Protection (which takes decisions for adults lacking mental capacity under the Mental Capacity Act 2005) authorising the sterilisation of a disabled man. The case, called DE, was decided on 16 August 2013.

DE is a man of 36, with a learning disability. His IQ was said to be 40, implying a mental age of between six and and nine. He is said to need ‘extensive support’ and has very limited speech. An earlier generation of psychiatrists would have categorised DE as an ‘imbecile’. Such a low IQ certainly suggests quite a significant level of mental impairment. DE lived with his devoted parents, who over the years had enabled DE to develop a modest degree of autonomy, such as walking to the gym with a friend, or travelling to a day centre on a bus by himself. Such developments took years to achieve.

DE formed a relationship with another learning-disabled woman, named PQ, whom he had known for 10 years. The local authority and the couple’s respective parents ‘supported’ the relationship.

The result of this well-meaning but short-sighted approach proved little short of disastrous. The couple started a sexual relationship, and PQ became pregnant. All hell then broke loose. PQ was accused of exploiting DE, and her baby was taken into care. DE was not allowed to see PQ unsupervised. As he did not even understand how a child had come into being in the first place, he had very little appreciation of why his routines were so disrupted. PQ, meanwhile, was told that having sex with DE was a crime, so she broke off their relationship, much to DE’s distress. Later, they became reconciled.

As a result of the reconciliation, DE’s parents requested that he be sterilised, to avoid any repetition of this crisis, which they found traumatic. DE said he did not want any more children. After a great deal of expert evidence, and some ‘education’ of DE by a learning-disability nurse and a clinical psychologist, the Court of Protection reached a somewhat contradictory conclusion. Firstly, DE had acquired capacity to consent to sexual relations, but secondly, he lacked capacity to use contraception. The court ruled that his best interests required sterilisation. It even reasoned that this would benefit DE’s parents, whose ensuing peace of mind would in turn benefit DE.

The ruling quotes slabs from other courts’ judgments, and argued that DE had ‘competing rights’ under Article 8 of the European Convention on Human Rights. This provision guarantees effective respect for a person’s private and family life. But to say that a person has competing rights is surely oxymoronic. One’s rights may compete with others’ rights, not one’s own.

A competent adult is free to decide which aspect of his private life means more to him: the certainty of knowing that he will not get a woman pregnant in future, which is another way of saying a choice never to become a parent; or opting for a less draconian, and possibly less reliable, method of birth control. An adult lacking capacity cannot make that choice.

While one can understand the court reaching the conclusion it did, on pragmatic grounds, this ruling has an air of smoke and mirrors about it. Should PQ and DE have been in a position to start a sexual relationship at all? And how can the issue of capacity to have heterosexual sex sensibly be viewed in isolation from the capacity to use birth control? Many people would see such a distinction as artificial.

Paradoxically, leaving the couple to their own devices resulted in far more state intrusion into their lives, and prolonged distress to them both, than if they had been chaperoned in the first place.

One standpoint is that those with learning disabilities should not be prevented from having sex, because it is pleasurable and a core element of being human. But this rose-tinted view is, arguably, unduly complacent. It would not be used to justify sex between, or with, young children. DE, with a mental age of between six and nine, sounded rather too impaired.

A curious feature of the case is that DE miraculously acquired the legal capacity to have sex during the proceedings. Again, this convenient development does not seem altogether convincing. DE’s cognitive deficits are enduring and lifelong. The idea that 14 hours of ‘direct work’, whatever that entailed, could remedy these deficits sounds optimistic. It is interesting that DE, according to the judgment, attended these sessions reluctantly.

As with so many cases in this jurisdiction, one can’t help feeling that the issues have been finessed so as to allay the professional anxieties of those involved, but without confronting more fundamental problems of the kind alluded to above. While the Court would no doubt claim to be handling difficult ethical and legal issues sensitively, the outcome is the same as if DE were alive in Virginia in the 1920s. This should give us pause.

The ruling has been hailed as a victory for autonomy and choice. In reality, however, what has happened is that others have imposed their own views of what is right for DE on to him. It is time to have a more open and democratic debate about whether and when our society deems it acceptable for the mentally disabled to have sex and start families, instead of leaving such decisions to be made behind closed doors by unelected judges.

Barbara Hewson is a barrister in London.

Who funds spiked? You do

We are funded by you. And in this era of cancel culture and advertiser boycotts, we rely on your donations more than ever. Seventy per cent of our revenue comes from our readers’ donations – the vast majority giving just £5 per month. If you make a regular donation – of £5 a month or £50 a year – you can become a and enjoy:

–Ad-free reading

–Exclusive events

–Access to our comments section

It’s the best way to keep spiked going – and growing. Thank you!

Comments

Want to join the conversation?

Only spiked supporters and patrons, who donate regularly to us, can comment on our articles.