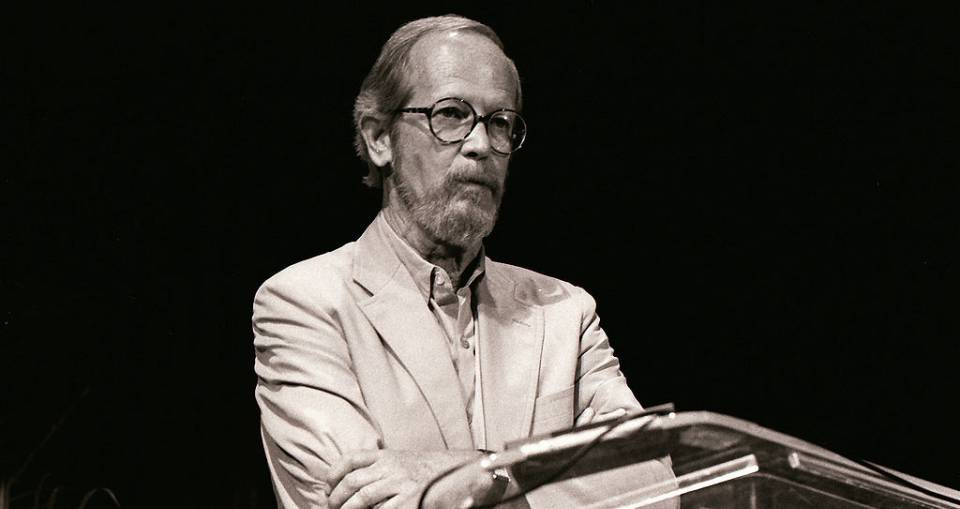

Elmore Leonard, king of crime

To mark the death of the genre-transforming writer, read this 1991 piece from Living Marxism.

Elmore Leonard, the crime writer responsible for such novels as Maximum Bob, Out of Sight and Get Shorty, died on Tuesday, aged 87. To mark his death, spiked is republishing this article, first featured in Living Marxism in November 1991, based on Leonard’s comments at an event at London’s Institute of Contemporary Arts.

Listening to crime writer Elmore Leonard, I got the feeling that pretentiousness must be his idea of the world’s deadliest sin. Everything about him seemed deliberately understated: his low-key delivery, his smart but not-too-smart get-up of blue blazer, white shirt and grey slacks. But the lowest of Leonard’s low-key traits was his assessment of his own writing: ‘Forty years ago it occurred to me this might be a good way to make a living. There’s no message. Entertainment, that’s all it is.’ He was talking about crime novels, set in Detroit and Miami, which have been described as the greatest chronicle of late twentieth century America.

Leonard doesn’t like to impose on his characters. Instead of traditional narrative, in which the author-as-unseen-observer describes events in his own distinctive voice, Leonard lets his characters speak for themselves. He chooses which character will describe a particular scene, and then reproduces ‘the sound of the character, even in narrative passages’. When Leonard ‘imparts whatever information I can through dialogue’ and ‘concentrates on the sounds of the voices’, he hopes that the reader is ‘never aware of me’.

Leonard’s characters have been known to perpetrate some fairly gruesome crimes, but he declines to ‘judge the people in my books’. If, in private, he takes a strong moral stance on the real-life equivalent of the fictional violence he describes, he doesn’t want the outside world to know about it. ‘You don’t hear me’, he says, coyly, ‘you’re never sure’.

Some writers map out their plotlines to the last detail before sitting down to write. This doesn’t appeal to Leonard. ‘When writing the first page, I have no idea [of the outcome]’. Leonard enjoys ‘not knowing what’s going to happen. That way I’m surprised’. Sometimes a character will put himself centre stage, or he could write himself out of the story altogether. ‘You never know who is going to be the main character until halfway through’, he said. Around halfway through Maximum Bob, the initial protagonist drives out of the novel and is never seen again. ‘I was surprised he lasted that long’, said Leonard. ‘The last time we see him he’s headed for California. I hope he makes it.’ The endings of Leonard’s novels can seem equally arbitrary. ‘They usually stop around page 360’, he quipped. In June [1991], Leonard finished Rum Punch, a novel about gun-running. When his editor complained that the ending was too abrupt, Leonard added three sentences, cut two, and went back to his vacation.

Is Leonard so shy and ineffectual that he dare not tamper with his own material? Nothing could be further from the truth. There is a case for arguing that Leonard made Eighties crime-writing his own, just as Dashiel Hammett and Raymond Chandler stamped their identities on the Thirties and Forties. What’s different about Leonard is that he got rid of the heroic hero. ‘What I’m up to is trying to be as realistic as possible, describing real criminals and law enforcement people as I know them.’ Now in his early sixties, Leonard came from a blue-collar background and he writes about ‘ordinary people into some kind of hustle’. His first crime novel was rejected 84 times by publishers who said, ‘there’s no one in this book to like’. Nowadays, many crime writers look up to Leonard and credit him with ‘making it okay to use the criminal as the main character’.

Leonard likes to make you think that all he has to do is sit at his desk and let his characters do the talking. But verisimilitude is an effect which is hard to obtain. Leonard’s writing style requires an unusually large amount of research. He now employs a full-time researcher to help him. He writes his first draft in longhand and then rewrites five or six times on the typewriter, constantly reading to himself to get the rhythms of speech just so. In Leonard’s case, producing entertainment requires a level of professional dedication which would defeat many who lay claim to the mantle of literature.

Leonard must be aware of this. He keeps up with the highbrow literary scene, although he sneers at the suggestion that he is trying to cross over into serious writing. His denial is so vehement it makes me wonder whether his deliberate self-effacement is really an inverted form of arrogance – the arrogance of a man who could outwrite John Dos Passos, but chooses not to try.

Leonard may be just a regular guy who values his privacy and doesn’t want to aim too high. On the other hand, he could be a much smarter operator. In an age like ours, lacking either certainty or direction, Leonard would not be the only one to cultivate the stance of not having a stance. Perhaps it has occurred to him that describing this uncertain mood – and not letting on – makes for a good living and good writing.

Andrew Calcutt is editor of Proof: Reading Journalism and Society. He is co-author, with Philip Hammond, of Journalism Studies: A Critical Introduction, published by Routledge. Buy this book from Amazon(UK).

Picture: Elmore Leonard, Miami Book Fair International, 1989, MDCarchives via Wikimedia Commons.

To enquire about republishing spiked’s content, a right to reply or to request a correction, please contact the managing editor, Viv Regan.

Comments

Want to join the conversation?

Only spiked supporters and patrons, who donate regularly to us, can comment on our articles.