‘Big History’: the annihilation of human agency

Meet the historians who treat mankind as the passive voyeur of the passing of time.

Want unlimited, ad-free access? Become a spiked supporter.

Debates about history, especially politicised debates, can give us striking insights into the prevailing cultural view of the human condition. Such debates send us signals – about what should be the focus of our loyalty and solidarity; about what role we think people play in the making of history; and most importantly of all about the legacy of humanity’s historical experiences, and what impact that legacy might have on the future.

Consider today’s constant calls to abolish the national focus of history in school curriculums in Western societies. The criticism of so-called nationalist history-teaching reflects an inability to give meaning to what were, until recently, taken-for-granted loyalties and shared assumptions. The vociferous campaign against the British Tory government’s attempt to reintroduce the ‘story of a nation’ into history-teaching was a success because not even the defenders of such teaching believed in it, never mind its opponents. Even someone like Richard Evans, who sports the title of regius professor of history at the University of Cambridge, now feels so estranged from the ancient traditions of his subject area that he can celebrate the new, non-nationalist history curriculum on the basis that ‘it recognises that children are not empty vessels to be filled with patriotic myths’.

Evans went on to argue that ‘history isn’t a mythmaking discipline, it’s a myth-busting discipline, and it needs to be taught as such in our schools’. Of course, busting myths is an honourable enterprise. But when it becomes the central purpose of a discipline, then the integrity of that discipline is compromised. Moreover, turning myth-busting into a standalone ideal – like its companion metaphor of ‘deconstruction’ – inevitably encourages uncritical criticism and cynicism. Certainly before children are let loose on the field of myth-busting, they would benefit from some familiarity with, and understanding of, the myths they are about to take apart.

Myth-busters are very selective about what kind of history they target. So whereas national history is denounced as ideological, other forms of history are offered a free pass. Evans wants British schools to put greater emphasis on European history rather than national history. His expansion of the scale of study is relatively modest in comparison with the current trend in history circles, which seeks continually to magnify history’s focus. There are frequent calls these days for global history, cosmopolitan history, Big History. As the Harvard professor David Armitage has argued, ‘Across the historical profession, the telescope rather than the microscope is increasingly the preferred instrument of examination’.

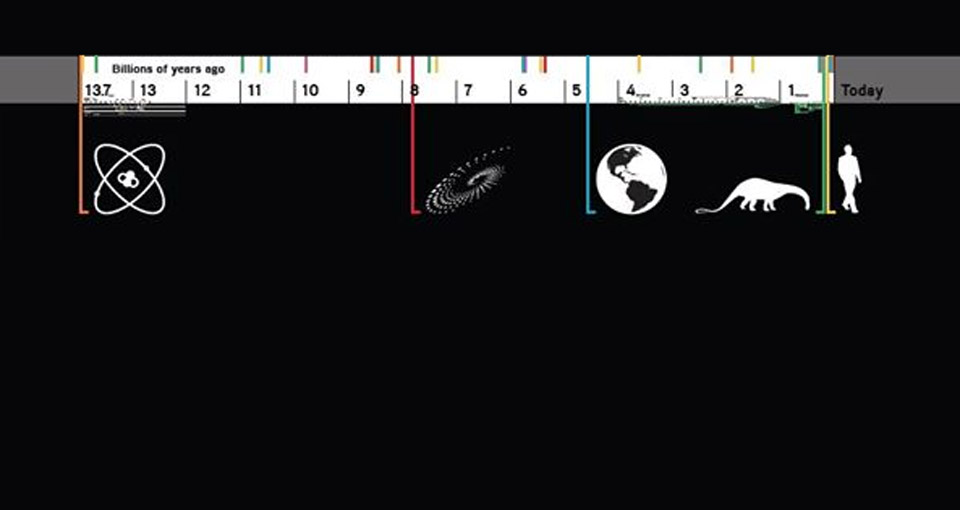

The proponents of the teaching of Big History claim to be driven by humanist sentiments. One, David Christian, says Big History offers a story that transcends the nation state and covers humanity as whole. He says that in his history courses, for example, you will ‘encounter humans not as Americans or Germans or Russians or Nigerians but as members of a single, genetically homogeneous, species, Homo sapiens’. You won’t only encounter humanity, in fact; Christian is proud of the fact that on his Big History course the species Homo sapiens is not even mentioned until halfway through. Is this really humanist? It looks to me more like the reduction of humanity to a biological species, and a sign that we are becoming increasingly estranged from ideas of civilisation, culture and community.

Outwardly, the calls for world histories or big histories look like contemporary versions of the universal histories of Oswald Spengler or Arnold Toynbee. In truth, though, their approach is directly antithetical to that tradition. Big History is not universal history. A truly universal history would take as its focus the significant human achievements that bind together people of different cultures. Rather than focusing on the biological and chemical make-up of a species, a universal history would explore the way different civilisations evolved, interacted and developed, and how they dealt with the shared challenges confronting humanity. In the Big History outlook, humans are seen as sharing, not historical inheritances, but natural ones. It is really a synthesis of what was once called natural history with evolutionary biology, geology and environmentalist ideology. That is why human beings are assigned a very limited role in Big History syllabuses – because, in Christian’s words, humans are ‘only part of the picture’ in this vision of history.

Yet history – universal or otherwise – should have as its focus the story and development of humanity. As Francis Fukuyama has noted, ‘A universal history of mankind is not the same thing as a history of the universe’. Fukuyama says of universal history: ‘It is not an encyclopaedic catalogue of everything that is known about humanity, but rather an attempt to find a meaningful pattern in the overall development of human societies generally.’ Inevitably, universal history has traditionally sought to delineate, very sharply, the distant past to which no human meaning could be assigned from human history itself.

Hegel’s Philosophy of History is invaluable in this respect. Hegel, one of the most influential nineteenth-century theorists of universal history, made a very clear distinction between the past and history. True history, he said, begins ‘at the point where rationality begins to enter into worldly existence’. He said the point of departure of history is when events begin to be interpreted and recorded as history. He said history requires concepts of individuality, rights and law, a ‘universally binding directive’, institutionalised through the State. His Philosophy of History sought to provide a philosophical-historical argument for the development of humanity’s self-conscious awareness.

Contrast Hegel with Big History, an idea now effusively promoted by the International Big History Association, an influential movement supported by Microsoft’s Bill Gates. This association’s version of history stretches back to the Big Bang itself. This so-called universal history is coterminous with the universe itself. It claims to synthesise virtually everything there is to know. Cosmology, astronomy, geology, evolutionary biology, archaeology and environmental science all make an appearance. This is history that self-consciously eradicates the conceptual distinction between nature and culture, between the material and the spiritual, between the human and the non-human. On its website, the International Big History Association says ‘Big History seeks to understand the integrated history of the Cosmos, Earth, Life, and Humanity, using the best available empirical evidence and scholarly method’. It goes on to assert:

‘Beginning about 13.8 billion years ago, the story of the past is a coherent record that includes a series of great thresholds. Beginning with the Big Bang, Big History is an evidence-based account of emergent complexity, with simpler components combining into new units with new properties and greater energy flows.’

Big History claims to be a response to the new complexities of our rapidly changing globalised world. In truth what it offers is a melange of everything that has occurred in time and space according to a naturalistic, teleological model of evolution. Although it relies on the ideas of evolutionary biology, geology, environmentalism and cosmology, its historiographical approach bears an uncanny resemblance to medieval theological-history. That is, Big History, like more medieval views of history, relies on a mythical-sounding narrative of origins, which implicitly endows the unfolding of time with purpose. To take one example of a Big History outlook:

‘What can we conclude from our 13.82billion-year journey so far in this universe? The access to high-quality energy in certain pockets has permitted increased complexity in relationships between quarks, atoms, molecules, cells, animals, and humans within families, cities, nations, empires, and the world. Each of the earlier relationships continue to be part of our current ones, although often in transformed ways. You and I are the beneficiaries of the relationships that have been developed. We are made from the relationships among quarks, atoms, molecules, cells, and many intricately related body parts. We live within kinship groups, nations, and empires. Many of us are connected with others around the world through the almost instantaneous exchange of digital information. We have evidence for a common origin of all of us and indeed everything in the universe. All of us on Earth have a common origin and ultimately a common destiny.’

Common origins? Only this time, our ‘common origins’ are not being located in the Garden of Eden. Nor does this new story of origins bear any resemblance to the Roman story of Aeneid. It is rather quarks, atoms and molecules that apparently embody our common origins. What we are being offered here is not the origins of humanity, but of matter.

Big History is not the only approach that attempts to decouple history from the human subject. So-called deep history is also devoted to eradicating the distinction between history and pre-history; indeed, its version of ‘history’ stretches back 2.6million years. The manifesto of this school of history, Deep History: The Architecture of Past and Present, complains about the ‘fragmentation of historical time’ that is apparently endemic in our era dominated by what deep historians call ‘shallow history’.

What is really at stake here is not the timescales being investigated by history, but the nature of historical imagination itself. The new historical outlooks seek to shift the focus of history away from any human-centred approach to the past, and towards the depiction of material and natural processes as the key influences on history. According to this viewpoint, anthropocentrist history, as the Big History people call it, is a conceit, since human beings have actually had very little to do with the really important events of the past 13 billion years. In effect, what used to be understood as history becomes a minor sub-branch of geology and biology. The emphasis on Big or Long or Deep history is underwritten by an (often unconscious) impulse to downgrade the humanist ideal of people making history.

The anti-humanist turn of history

It is of course true that the more we look back in time, the more we see humanity being dominated by nature. Tens of thousands of years ago, human beings played an insignificant role in the making of their world; hundreds of thousands of years ago, none at all. The lengthy timescale of Big History – the more than 13 billion years since the Big Bang – speaks to an imagination keen to relegate human accomplishment to a minor footnote. That is why in the syllabuses offered by Big Historians, the human species does not make an appearance until much later on in the course or study.

The assignment of a marginal role to human beings is also a favoured pastime of twenty-first-century environmentalists. From the standpoint of green ideology, a massive timescale is preferable when discussing history, because the further back in time you go, the more insignificant is the role of human beings relative to that of nature.

These new historic accounts all conclude with the same point – which is that although Earth has existed for about 4.5 billion years, Homo sapiens have been on this planet for barely a couple of hundred thousand years. The moral of the story is that human beings should be a bit more aware of their own insignificance as a species. If we take history as spanning billions of years, then we must look upon humans as not causing anything of great significance. Instead, human beings are reduced to the level of passive spectators of climate change, massive earthquakes, huge eruptions. Instead of serving as history’s subject, people are transformed into history’s objects. As one anti-humanist writer puts it:

‘Earth has existed for about 4.5 billion years and has experienced numerous transitional changes. Homo sapiens has been on the planet about 160,000 years – a small portion of total time. For most of the time, the human species was spread thinly over the planet with minimal environmental impact.’

Human inconsequentiality – that is the key theme promoted by those who take a naturalistic and physical perspective on the past.

All histories convey some kind of meaning, some kind of moral view of human beings and their achievements. The new historians of human irrelevance seem, outwardly at least, to eschew meaning and purpose through emphasising a vast timescale and a spectrum of arbitrarily assembled occurrences that cannot be meaningfully put in a relation to one another. In truth, despite their one-sided materialistic and mechanistic narratives, such histories still convey a sense of meaning, in the negative sense of warning that what human beings do does not matter very much. From this perspective, history is definitely not made by people; we are simply the passive voyeurs of big events.

Today’s cultural imagination seems to have little appreciation of, or even belief in, the history-making potential of humanity. On the contrary, there has been a fundamental shift towards a tendency for writing humanity out of history. Not since the Middle Ages has the human species been accorded such an insignificant status in the making of history. A new school of naturalistic history seems to revel in lowering people’s expectations of what they and their species can achieve. It promotes a sense of environmental determinism that assigns human beings a minor role in the general scheme of things. It insists that any attempt by people to gain control over their destiny is likely to be undermined by the forces of nature. Not surprisingly, it continually emphasises environmental factors, particularly geology and climate, giving the impression that history is made by natural occurrences rather than human choices and action.

In fact, mankind’s very attempt to control nature is now depicted as destructive and dangerous, a sign that our species does not know its place in the natural order of things. Far from man’s attempts to transform nature being celebrated, today history and civilisation have been recast as stories of environmental destruction. Our application of reason, knowledge and science is seen as problematic, because it apparently helps to intensify the destructive capacity of the human race. Something like the Enlightenment is now looked upon as a malevolent thing that promoted the destruction of the planet, through its arrogant elevation of rational, history-making man.

The new conservatism

Critics of national histories often dismiss them as conservative myth-making. However, today’s Big Histories are more reactionary than national history. As in ancient and medieval historiography, the search for roots in the past implies an analogy between natural and social life. This obsession with an origins story gives human experience and development a very fatalistic character. Apparently, just as the roots of a tree determine the pattern of its subsequent development, so the human past determines our future.

This trend for externalising human subjectivity fails to grasp or understand the relationship between the present and the past. A serious consciousness of history, or historical thinking, is based on the recognition that human intervention plays a fundamental role in social development; that is, the present we find ourselves in is the result of the actions of human beings. The insight that humans make themselves, and are not simply the products of nature, was grasped by the leading thinkers of the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries. Despite his eventual turn towards conservatism, Hegel argued against the medieval notion that human nature was fixed and unchanging. He claimed that the most distinctive feature of human beings was not their biology but the fact that their humanity was undetermined, the fact that they possessed the potential to create their own nature.

Today’s disenchantment with historical thinking and devaluation of human subjectivity speak to society’s ambiguous attitude towards the legacy of the Enlightenment. Formally, people refuse to defer to Fate and spend considerable time, energy and resources trying to gain a measure of control over their lives. But at the same time, the conviction that this is it, that there is no alternative, has a powerful grip on public life and attitudes. Anti-humanist sentiments prey on our imaginations, encouraging us to regard the future with dread.

There is a reason that the Big History advocates are particularly hostile towards national history. It’s because through focusing on the global, they can further emphasise the insignificance of individuals and mankind more broadly. On the world stage, the influence of external forces over the individual is even more overwhelming than it is within their own communities or national settings. And since global relations can be depicted as complex and contingent, as ever-changing, cosmopolitan historians are spared the responsibility of endowing their story with any tangible meaning. No meaning, and of course no myths. Such a history does not bust myths; it merely negates the search for truth.

Frank Furedi is a sociologist and commentator. This is an edited version of a lecture given at the Academy 2013.

You’ve hit your monthly free article limit.

Support spiked and get unlimited access.

Support spiked and get unlimited access

spiked is funded by readers like you. Only 0.1% of regular readers currently support us. If just 1% did, we could grow our team and step up the fight for free speech and democracy.

Become a spiked supporter and enjoy unlimited, ad-free access, bonus content and exclusive events – while helping to keep independent journalism alive.

Monthly support makes the biggest difference. Thank you.

Comments

Want to join the conversation?

Only spiked supporters and patrons, who donate regularly to us, can comment on our articles.