Inferno: the lovechild of Wikipedia and Malthus

With its clotted prose, list of historical facts, and sub-plot about humans breeding like rabbits, Dan Brown’s latest is a depressing read.

Want to read spiked ad-free? Become a spiked supporter.

Dan Brown’s latest blockbuster is great fun for fans of trivial pursuit, but not for fans of good fiction.

The latest Dan Brown blockbuster, Inferno, tempts me to ridicule its pretentious cultural references, its cardboard characters, and its insipid prose. Is this craven jealousy of a bestselling author? Perhaps. Is this a lack of compassion for the disabled? Almost certainly. But as Oscar Wilde sagely observed, ‘The only way to get rid of a temptation is to yield to it’.

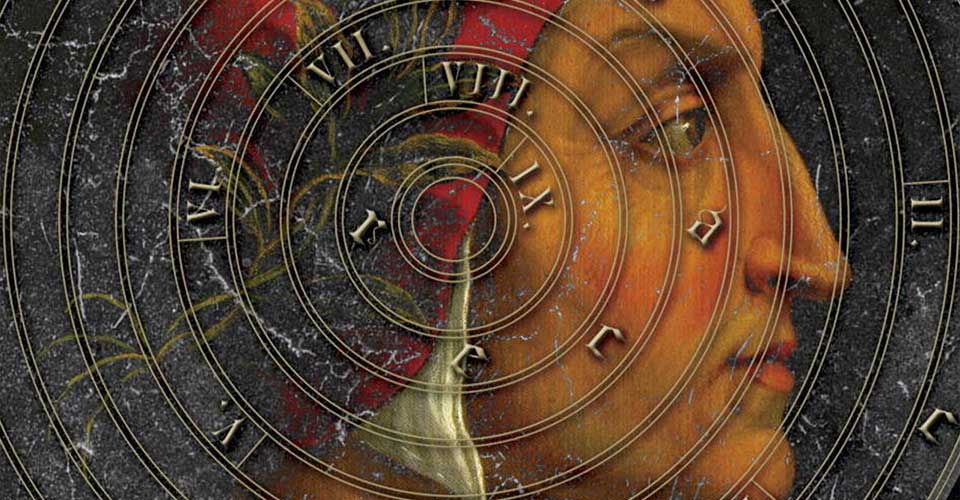

There is no point in treating Inferno as a work of art. It is a business product, a calculated assault on the pocketbooks of bored travellers in airport lounges. Brown’s forte is an ability to weave an exhausting session of Trivial Pursuit into a one-twist-per-chapter plot. It’s a good script for a video game, but it’s not literature. Inferno, like The Lost Symbol and The Da Vinci Code, is the love child of Wikipedia and crass commercialism.

Without giving away the plot, here is an overview. Harvard symbologist Robert Langdon wakes up in a hospital in Florence with mild amnesia. A woman with spiked hair breaks in and kills his doctor. Still groggy and trailing his tubes, he flees with a young woman named Sienna Brooks. At her flat he discovers that his Harris Tweed jacket contains a cylinder with an ominous message based on Dante’s Divine Comedy. The future of the world is at stake and only Langdon can save it. Suddenly…

You get the idea.

In the era of postmodernism, every text can be deconstructed. From that point of view, there is something genuinely intriguing about Brown’s formulaic writing. Inferno, like the other Robert Langdon novels, is a collage of bits and bobs from high Western culture experienced without a coherent narrative. It appeals to readers’ bowerbird desire to collect glittering factoids about a past which most of them do not understand or appreciate.

Consequently, reading Inferno is like surfing through Wikipedia entries on Florence, Venice and Istanbul. I wonder if the tourism authorities in these cities paid Brown to promote their attractions in the novels. Crowds are sure to follow the tracks of Harvard ‘symbologist’ Robert Langdon and Sienna as they flee from police, agents of the World Health Organiation and assassins.

Brown will never be described as a literary giant, but there is one technique in which he has no peer: product placement. As Robert Langdon effortlessly unravels the mysteries of the Divine Comedy, I couldn’t help reflecting that the real mystery is why readers aren’t repelled by the blatant spruiking. Here’s a typical passage which burnishes the brands of both Google and Apple:

‘Langdon thanked her and took the phone. While she prattled on beside him about how terrible she would feel if she lost her iPhone, Langdon pulled up Google’s search window and pressed the microphone button. When the phone beeped once, Langdon articulated [ie, spoke] his search. “Dante, Divine Comedy, Paradise, Canto Twenty-five.” The woman looked amazed, apparently having yet to learn about this feature.’

Other brands with glowing references are NetJet, a private jet company; Grand Hotel Baglioni, in Florence; Frecciargento trains; Harris Tweed; the Canadian singer Loreena McKennitt; and a Dubois SR52 Blackbird luxury cruiser.

The villain of the novel is a Swiss biochemist billionaire named Bertrand Zobrist. He perishes in the opening chapter (although he resurfaces in a couple of brief sex-scene flashbacks). But as I descended deeper and deeper into Inferno, I began to regard the real villain as Dan Brown’s editor, whom, out of what little compassion I can scrape together, I shall not name. His only credible excuse is that Dan Brown is one of those nightmare celebrity authors whom editors tremble to correct. Otherwise, how did sentences like these pass muster?

‘He had always enjoyed the solitude and independence provided him by his chosen life of bachelorhood, although he had to admit, in his current situation, he’d prefer to have a familiar face at his side.’

‘He opened one of the boxes and retrieved its contents – in this case, a bright red memory stick.’

‘She found herself strangely attracted to the American professor. In addition to his being handsome, he seemed to possess a sincerely good heart.’

And how did the word ‘enormity’ slip through, as in ‘the staggering force of [the cathedral’s] enormity’ and ‘the David’s [Michelangelo’s statue] sheer enormity’? Enormity means, according to my Oxford dictionary, ‘monstrous wickedness’ or ‘dreadful crime’, or ‘serious error’. We can speak, for example, about the enormity of Dan Brown’s English, but not about the enormity of a cathedral.

In short, the appropriate tagline for Dan Brown’s literary style is not ‘the sparkle of champagne’ but ‘peanut butter and jelly for the mind’.

How about the ideas? Brown insists that he wants to alert his readers to serious issues. In Inferno, these are twofold (which weakens the plot) – transhumanism and overpopulation.

Transhumanism, which political scientist Francis Fukuyama once called the world’s most dangerous idea, is a cockamamie philosophy advocating artificially accelerated evolution. It is definitely quite loopy, so Dan Brown has done readers a service in alerting them to its existence. However, its enthusiasts, for the most part, are anarchic and disputatious geeks, so it’s hard to imagine that they could ever organise themselves into a vast conspiracy to devastate humanity.

Overpopulation, on the other hand, is gospel truth for Dan Brown. Amid the clotted prose, the pages which describe a planet pullulating with people glow with evangelistic intensity.

‘“We are an organism that, despite our unmatched intellect, cannot seem to control our own numbers [says Sienna]. No amount of free contraception, education, or government enticement works. We keep having babies … whether we want to or not. Did you know the CDC just announced that nearly half of all pregnancies in the US are unplanned? And, in underdeveloped nations, that number is over seventy per cent!” Langdon had seen these statistics before and yet only now was he starting to understand their implications. As a species, humans were like the rabbits that were introduced on certain Pacific islands and allowed to reproduce unchecked to the point that they decimated their ecosystem and finally went extinct.’

Great novelists are said to be clairvoyants who channel the perils and anxieties of the future. But Dan Brown is channelling the discredited nineteenth-century miserabilist Thomas Malthus. Perhaps it is another example of product placement. One of the characters, the head of the World Health Organisation, says that ‘Bill and Melinda Gates deserved to be canonised for all they’d done through their foundation’ to help improve access to birth control around the world.

Don’t tell me that Dan Brown canonised the richest man in the world for nix!

Overpopulation? Has Dan Brown been living in a bunker for the past 10 years? Nearly everywhere, fertility rates are collapsing. After reaching a peak of about nine billion in the year 2050, global population is going to fall. In some countries, it will fall so sharply that it could provoke economic catastrophes as dwindling proportions of young workers stagger under the burden of supporting the elderly and disabled. Already there is below-replacement fertility in Italy, depopulation in Japan, labour shortages in China, and declining illegal immigration into the US from Mexico. Paul Ehrlich’s 1968 book The Population Bomb was a damp squib.

A bit like Inferno.

Michael Cook is editor of MercatorNet.

Who funds spiked? You do

We are funded by you. And in this era of cancel culture and advertiser boycotts, we rely on your donations more than ever. Seventy per cent of our revenue comes from our readers’ donations – the vast majority giving just £5 per month. If you make a regular donation – of £5 a month or £50 a year – you can become a and enjoy:

–Ad-free reading

–Exclusive events

–Access to our comments section

It’s the best way to keep spiked going – and growing. Thank you!

Comments

Want to join the conversation?

Only spiked supporters and patrons, who donate regularly to us, can comment on our articles.