A newspaper bans its own Nick Cave story – the Twittermob strikes again

The ease with which mobs can demolish content is terrifying.

The power of the Twittermob has officially crossed the line from ‘worrying’ to ‘terrifying’. Yesterday, these ready offence-takers, these always primed chest-beaters over words and images that don’t gel with the moral outlook of the Twitterati, managed to get a newspaper article expunged from the internet, shoved down the memory hole, made into an un-article so that it would never again offend their sensibilities. And they destroyed the article with such swiftness that many people won’t even have noticed that it happened. But it did happen, and we need to talk about it.

The article appeared in the print edition of The Times yesterday. It was about the tragic death of Arthur Cave, son of singer Nick Cave. Arthur fell from a cliff in Brighton on Tuesday. Under the headline ‘Let your children feel fear, Cave urged before son’s death’, The Times news item pointed out that, in an interview with the magazine Kill Your Darlings published just last week, Nick Cave talked about the importance of allowing children to feel fear, where the adult ‘must stand back and let the child decide’. The Times piece wasn’t especially gratuitous or insulting to Cave; indeed, it said he had ‘spoke[n] poignantly about his anxiety at seeing his children face up to danger’. It was basically pointing to the horrible irony of the fact that, in the space of a fortnight, Cave had talked about allowing children to ‘face down… a terrifying situation’, which he described as ‘one of the most moving things an adult, particularly a parent, can witness’, and then had to bear the loss of his son in a terrifying situation. Pulitzer Prize-winning journalism? No. Horribly offensive? No.

But the itchy fingers and intolerant minds of the Twittermob weren’t having it. They branded The Times‘ article an intrusion into Cave’s grief and unleashed fury and expletives against it. One, a Guardian journalist, said The Times were ‘fucking creeps’, and the article was ‘baseless, pointless, insinuating shit’. The storm built and others were soon raging against this ‘appalling’, ‘disgraceful’, ‘cheap and tacky’, ‘vile’, ‘pointlessly cruel’, ‘shameful’ article. What the Twittermob lacks in level-headed reason it more than makes up for with angry adjectives. One member of the Twittermob even unsubscribed from The Times and wrote an open letter explaining why, because what’s the point in making a Big Moral Statement about your implacable decency if you don’t then advertise it to the whole internet? (What’s with all the open letters these days? Someone should write an open letter telling all the irritants writing open letters to please stop.)

‘Shameful’ was the most common word hurled at The Times. It should be ‘ashamed’ for having published that article. ‘Bloody ashamed’, in fact. Some contacted the individual journalists who wrote the article to inquire if they were feeling ashamed, which they bloody well should have been. The Twittermob, like a fuming priest, loves nothing better than to induce feelings of shame in any hack / troll / misspeaker who says something odd, outré or offensive. ‘SHAME!’ they scream, like pulpit-dwellers of old keen to make their dumb ignorant flock feel awful about something they said or did.

And here’s the terrifying thing: the Twittermob’s blanket of shame cast over The Times yesterday actually worked. The Times removed the article from its website. Which means people can no longer read it. Oh, let’s call a spade a spade – the article has been banned. And banned, it seems, at the behest of a noisy online mob. As the Guardian put it, ‘Times newspaper removes Nick Cave story after online complaints’. ‘Online complaints’ – nice. Makes it sounds like people politely filled in a form saying ‘This article was upsetting’, when in truth they fucked and cunted at The Times and invited these ‘scum suckers’ to feel great shame about their ‘vileness’. And The Times bowed to them. It said its story was ‘inappropriate’ and would no longer be available for the public to read. (But The Times has ‘yet to issue a public apology’, complains the Guardian. Because even self-censorship isn’t enough for the shame-spreaders of Twitter. They want contrition, regret, expressed as publicly as possible, as was done by misspeakers in the Soviet Union.)

Having won the obliteration of a piece of written material that offended them, the Twittermob then gloated. Fashion writer Eva Wiseman cheered The Times‘ self-squishing of its offensive article ‘after everybody in the world just screwed up their faces like “ffs”‘. The arrogance, not to mention self-delusion, is astounding. ‘Everybody in the world’? This Twittermob was a tiny collective of ageing rock critics, bored online offence-hunters, and Murdoch-loathers. I’d say it was closer to 70 people than seven billion.

The memory-holing of a newspaper article in the space of a few hours, following yelps of outrage from tens of touchy people, is a scary sign of the times. It points to the post-Leveson symbiotic relationship between the outraged content-policers of Twitter and an increasingly cagey press. The climate stoked in recent years by both informal Twittermobs and formal inquisitions into the culture and ethics of the press has had a chilling effect on media debate, making newspapers more cautious and self-censoring. Whether it’s the Observer pulling a Julie Burchill column after Twitter-based trans activists went mad about it, or The Economist officially unpublishing a book review on slavery after a Twittergang branded it offensive, or The Times wiping one of its own news reports on Nick Cave in response to ‘online complaints’, a clear message has been sent: big media publications will destroy their own material if you, small but vocal Twittermob, judge it to be offensive. Well done, media: you’ve empowered the intolerant Twittermob; you’ve green-lighted their unwieldy, free-floating censoriousness, which can strike anywhere, anytime.

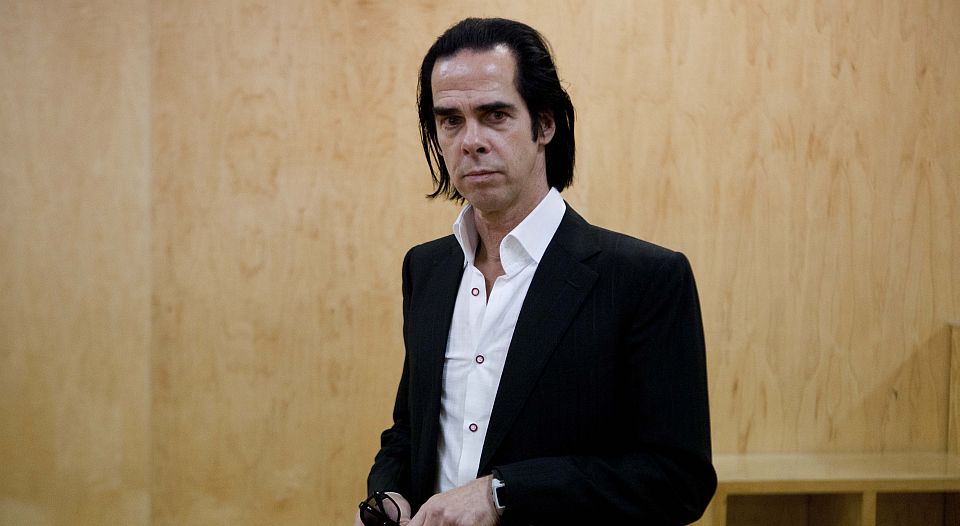

For the record, I love Nick Cave, the suavest, most talented man in popular music. And I think his comments about allowing children to experience fear, and decide for themselves on the best course of action to take, were searingly sensible in this era of cotton-wool kids, when we seek to protect children from everything. And the awful death of his son does nothing whatsoever to detract from the rightness and humanity of his comments. I also haven’t been a massive fan of some of the press coverage of his son’s death, especially the publication of photos of Nick and his wife visiting the spot where Arthur fell.

But you know what? I would far rather live in a country in which the press publishes daft articles and offensive photos than a country in which infinitesimally small groups of professional furies can demolish opinion columns, book reviews, news pieces and any other written thing that upsets them. A free press that sometimes does dumb things is so much better than a press that can overnight be induced to self-flagellation and self-censorship by the new moral guardians. Because if we have the latter, then we’re essentially okaying tyranny, allowing tiny groups of the self-righteous to sit in judgement on which media content is ‘appropriate’ and which is ‘inappropriate’. Oh, the irony: the Twittermob loves to heap shame on the offensive, yet it does something way more shameful – it reintroduces censorship by the backdoor, in the most slippery language imaginable, dressing up its censorious fury as ‘online complaints’.

Brendan O’Neill is editor of spiked.

Picture by: Eduardo Verdugo / AP/Press Association Images

To enquire about republishing spiked’s content, a right to reply or to request a correction, please contact the managing editor, Viv Regan.

Comments

Want to join the conversation?

Only spiked supporters and patrons, who donate regularly to us, can comment on our articles.