Long-read

Living towards the past

Zygmunt Bauman talks retrotopia and humanity's disillusionment with the future.

Want unlimited, ad-free access? Become a spiked supporter.

Zygmunt Bauman’s nine decades have been lived close to the marrow of history. Born in 1925 to non-practicing Polish-Jewish parents in Poznan, his family fled to the Soviet Union in 1939 as Nazi tanks rolled into Poland. Having served in the Red Army with distinction, he returned to Poland after the Second World War to study sociology at Warsaw University. But, with Communism having long since lost its lustre and his academic career impeded by anti-Semitism, he emigrated to the UK in 1968, where he took up a chair of sociology at the University of Leeds. But it’s after his retirement in 1990 that the probing intelligence, for which he is so renowned, started to generate book after book. Intimations of Postmodernity (1992); Liquid Modernity (2000); Society Under Siege (2002); Strangers at Our Door (2016)… The list goes on. In fact, over the past quarter century he has published some 40 books, not for the sake of it, but because the world as it is is not how he feels it ought to be. Or, as he put it in 2003: ‘Why do I write books? Why do I think? Why should I be passionate? Because things could be different, they could be made better.’

The exchange below took place earlier this year after an initial question about the significance of the EU referendum result (published in August’s spiked review) prompted the following conversation about the future, the past and the fate of the Enlightenment project.

spiked review: You’ve spoken before of popular disillusionment with national politics in a globalised world, and people’s sense that national politicians are powerless to affect change. Have your views changed in light of the EU referendum and the prospective Brexit?

Zygmunt Bauman: I believe that the collapse of trust in the capability of all (I repeat all) parts of the territorially sovereign state’s political establishment across the developed world to deliver desired change (or indeed any promised change) is precisely what, paradoxically, has sedimented the Brexit phenomenon.

With voters’ frustration with the political elite complete, and their total refusal to invest trust in any part of the political elite, the referendum provided an unprecedented opportunity to match the polling choices with the sentiments struggling for expression. It was a unique occasion, in that respect, and so very different to routine parliamentary elections!

At a General Election, you may express your frustration, your anger against the most recent in a long line of power-holders and promise-givers. But the price you pay for this emotional relief is merely to invite Her Majesty’s Opposition, an inseparable part of the political establishment, to enter ministerial offices as Her Majesty’s Government. In this endless game of musical chairs, you come nowhere near to expressing the total, comprehensive nature of your dissent.

The occasion offered by the Brexit referendum was completely different. With nearly all sectors of the political establishment positioning themselves on the Remain side of the division, you could use your single vote for Leave to release your anger against all of them in one go. The more all-embracing your frustration, the more tempting it becomes to do just that — to grasp that once-in-a-lifetime opportunity to vent your anger.

review: You’ve written of the end of progress, the loss of belief in the idea that the future will be better than the past. Is there anything in the Brexit phenomenon (and, indeed, other populist movements on the continent) that promises a new, perhaps even better era for Europe?

Bauman: We still believe in ‘progress’, but we view it now as both a blessing and a curse, with the curse part growing steadily, while the blessing part is getting smaller. Contrast this with the attitude of our most recent ancestors – they still believed the future to be the safest and most promising location for hopes. We, however, tend to locate our fears, anxieties and apprehensions in the future: of growing job scarcity; of falling incomes and so also of the decline of our and our children’s life chances; of the increasing frailty of our social positions and the temporariness of our life achievements; of an unstoppably widening gap between the tools, resources and skills at our disposal and the grandiosity of life challenges; of the control over our lives slipping from our hands. It’s as if we, as individuals, are being degraded to the status of pawns on the margins of a chess game being played by persons unknown. They are indifferent to our needs and dreams, if not downright hostile and cruel, and are all too ready to sacrifice us in pursuit of their own objectives.

What the thought of future tends nowadays to bring to mind, therefore, is the growing menace of being discovered and classified as inept and unfit for task, denied value and dignity, marginalised, excluded and outcast.

A rising majority of people have by now learned from their own experience, and that of their nearest and dearest, to discredit the uneven, capricious, unpredictable and notoriously disappointing future as the location for investment of hopes. My latest book, Retrotopia, touches precisely on these issues. Let me quote a fragment from its introduction:

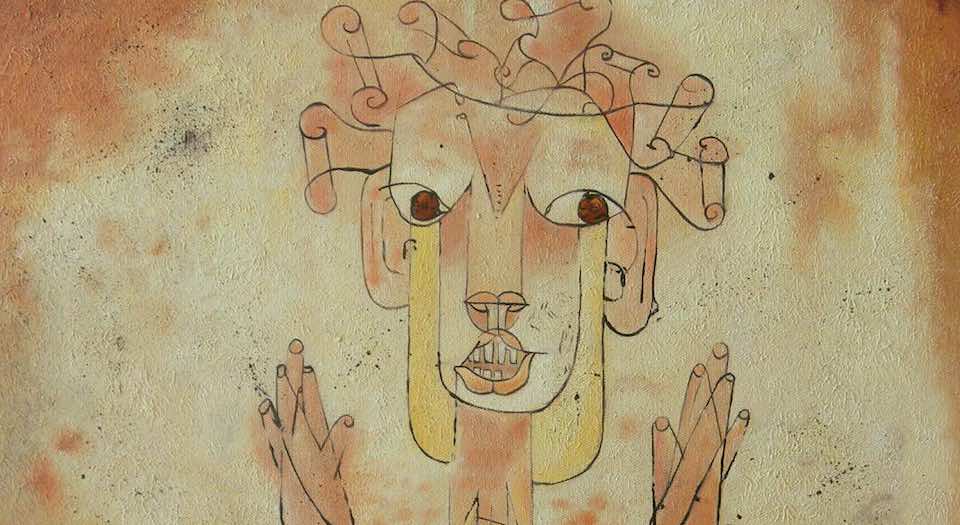

‘This is what Walter Benjamin had to say in his Theses of the Philosophy of History, written in early 1940, about the message conveyed by Angelus Novus (renamed Angel of History), a 1920 Paul Klee painting:

“The face of the Angel of History is turned towards the past. Where we perceived a chain of events, he sees a single catastrophe which keeps piling wreckage and hurls it in front of his feet. The angel would like to stay, awaken the dead, and make whole what has been smashed. But a storm is blowing from paradise; it has got caught in his wings with such violence that the angel can no longer close them. This storm irresistibly propels him into the future to which his back is turned, while the pile of debris before him grows skyward. The storm is what we call progress.”

Were one to look closely at Klee’s drawing almost a century after Benjamin produced his unfathomably, incomparably profound insight, one would catch the Angel of History once more in full flight. What might however strike him or her most, is the angel changing direction – the Angel of History caught in the moment of a u-turn. His face is turning from the past to the future, his wings being pushed backwards by the storm blowing this time from the imagined, anticipated and feared-in-advance future towards the paradise of the past (itself retrospectively imagined after having been lost and fallen into ruins). And the wings are being pressed now, as they were pressed then, with equally mighty violence so that now as then “the angel can no longer close them”.

Past and future, one may conclude, are in the process of exchanging their respective virtues and vices, listed – as suggested by Benjamin – a hundred years ago by Klee. It is now the future that is booked on the debit side, having been first decried for its untrustworthiness and unmanageability, with more vices than virtues, while it is the turn of the past, with more virtues than vices, to be booked on the credit side – as a site of still free choice and the investment of still undiscredited hope.’

I believe that the Brexit episode, as well as ‘other populist movements on the continent’, are manifestations of the above discussed ‘retrotopian tendency’. In the absence of effective tools of action capable of tackling the problems of our present situation, and given the rising number of disappointments brought by successive futures credited with developing these tools of action, it is hardly surprising that the proposition of the u-turn of exploration looks misleadingly attractive. The possibility of ‘a new, perhaps even better era for Europe’ emerging in the aftermath of Brexit, may yet appear, as its unanticipated yet plausible consequence. But that will be because we become frustrated with the use of antiquated tribalisms to deal with the present-day challenges generated by the emergent globalised human condition of worldwide interdependence.

review: The idea of a retrotopian tendency does make sense, given the widespread fear of the future. But how do you account for the co-existing tendency to view the past as a negative moral absolute, a way, if you like, of morally orienting ourselves in the present by saying ‘we know we are against that’ or ‘never again’? I’m thinking here of the centrality of the Holocaust to contemporary political and historical discourse, which has really come to the fore over the past 20 years. And I’m also thinking of the recent but continued focus on historical sex crimes in the UK, where it often seems as if the relatively recent past is being turned into a site of barely believable corruption and immorality against which we affirm ourselves in the present. The future certainly seems discredited today, but is the past not equally so?

Bauman: Isaac Newton insisted that each action triggers a reaction… And Hegel presented history as a strife/friction between mutually prompting and reinforcing oppositions (the intertwined cancellation and absorption process known as ‘dialectics’). Were you to start from Newton or Hegel, you’d arrive at much the same conclusion: namely, that it would be indeed bizarre if the retrotopian tendency was not fed by and feeding the future’s enthronement and dethronement (your question above being, by the way, a good example of that dialectics).

Retrotopia, just as the orthodox Future-utopia, refers to a foreign land: unknown, unvisited, untried and, all in all, un-experienced territory. This is precisely why retrotopias and utopias are resorted to, intermittently, whenever an alternative to the present is sought. Both are, for that reason, selective visions, and in both cases they are selective visions that are obediently and obligingly amenable to manipulation. In both cases, the floodlights of attention are focused on some aspects of, to quote Leopold von Ranke, wie es ist eigentlich gewesen [how it really was] but in a dense shadow. This allows both to be ideal (imagined) territories on which to locate the (imagined) ideal state of affairs, or at least a corrected version of the present state of affairs.

So far, utopia and retrotopia don’t differ – at least in their proceedings and the partiality of results. What really sets one apart from the other is the changing of places between trust and mistrust: trust being moved from future to the past, mistrust in the opposite direction. Your own example captures that process, implying as it does that the unavoidability of the ‘retrotopian tendency’ coincides with the popularity of ‘never again’. After all, retrotopia derives its attraction, among other factors, from the ‘never again’ sense that the future may, and is likely to, ‘do it again’. That ‘centrality of the Holocaust to contemporary political and historical discourse, which has really come to the fore over the past 20 years’, which you so rightly note, wouldn’t otherwise happen. It testifies to the collapse of confidence in the future’s ability to raise moral standards.

review: You talk, correctly I believe, of this intense mistrust of the future, which, in turn, generates these retrotopian dreams of a past that never was. But why has the future ceased to be the location for our hopes, the space in which we imagine and envisage how things ought to be? You partially answer this where you note that ‘a great and rising majority of people have… learned… to discredit the uneven, capricious, unpredictable and notoriously disappointing future’. But European history is pockmarked by the experience of assorted horrific events which did not necessarily result in a widespread loss of faith in the future. For instance, the Thirty Years War was followed by the first stirrings of the Enlightenment, one of the most future-oriented and optimistic of cultural moments. Even after the catastrophe of the World Wars and the Holocaust, the postwar period, up until the 1970s, was arguably marked by a degree of optimism, that things were getting better, indeed, ‘that you’ve never had it so good’, and then, of course there was the Sixties, a moment of great social and political experimentation.

So what is it about life in society today that has rendered the future up as something to be mistrusted, to be feared even?

Bauman: Thinking of the future ‘as something to be mistrusted, to be feared even’, is by no means novel in human history. In fact, it goes back to pre-Socratic times, more precisely, to the 8th century BC – to Hesiod’s Works and Days, and in particular the story of the ‘Ages of Men’ it contains. This was a story of continuous decadence, corruption and degradation, from the ‘golden age’ peak to the ‘iron age’ bottom of bottoms, in which Hesiod located himself together with his contemporaries. His description of the condition and dynamics of the iron age’s inhabitants was strikingly reminiscent of the characteristics our own contemporaries impute to our own 21st-century condition when embarking on the retrotopian journey; that is, it was atrocious, horrifying and repulsive.

As Hesiod saw it, the ‘race of iron’ was doomed ‘never to rest from labour and sorrow by day, and from perishing by night’. In the age of iron, ‘the father will not agree with his children, nor the children with their father, nor guests with their host, nor comrade with comrade’, and ‘there will be no favour for the man who keeps his oath or for the just or for the good; but rather men will praise the evil-doer and his violent dealing. Strength will be right, and reverence will cease to be; and the wicked will hurt the worthy man, speaking false words against him, and will swear an oath upon them.’ In the iron age, aidos (the Greek name for the feeling of reverence, and also for the shame which restrains people from wrongdoing) will be increasingly conspicuous by its absence only.

In its reaction to the heritage of pagan Greece, Christian Europe introduced a third element to the Hesiodic cycle of decline and fall: redemption, the prospect of chronological reversal of golden and iron eras. Saint Augustine, for instance, introduced a linear concept of time that flowed from the inferior City of Man, worm-eaten by indelible traces of original sin and, like Hesiod’s iron age, endemically corrupt, to the perfection of the City of God, led by the Christian church, the avant-garde and the place d’armes. In the Middle Ages up until the modern age, however, the predominant model of time-flow was closer to Hesiod’s than to Saint Augustine’s.

During the Renaissance, things change. Francis Bacon dared to visualise the rule of salomon’s house, the ideal college in his utopian work New Atlantis, as the culmination of the long, wobbly and thorny upward climb of humanity to a new golden age. And in an attempt to go beyond the querelle des anciens et des modernes, Isaac Newton tried to put sticks in both warring anthills, proclaiming in a letter to Robert Hooke on 5 February 1675: ‘If I have seen further it is by standing on the shoulders of giants.’

In the interests of simplifying this convoluted story of inter-crossing, inter-twining, mutually inspiring and reciprocally detracting lines of thought, I suggest the year 1755 as the watershed point separating the two competing visions of apocalyptic decline from the beginning of men-designed and men-guided history – the emergence, that is, of a vision of continuous, essentially unstoppable progress. In that year, an earthquake, followed by fire and succeeded by deluge, combined to wipe the city of Lisbon from the face of the earth. At that point, Lisbon was admired and revered as one of the richest and most powerful economic and cultural citadels of what, by its own definition, constituted the avant-garde of the civilised world. To put it in a nutshell: now standing charged with its endemic indiscrimination, moral numbness and dumbness, as well as indifference to human ethics and values, nature – that order established by Deus (since then absconditus, leaving the fate of humans to their own ingenuity and inventiveness) – needed to be taken under new human management.

The new management was sternly and resolutely forward looking. ‘New’ turned into the tautology of ‘improved’ and ‘better’, as much as the ‘old’ turned into a pleonasm for ‘old-fashioned’ and ‘outdated’. In the process, this transformed the extant and soon-to-be old into the realm of condemnable imperfection, earmarked for waste disposal. And it expanded the space of desirable and welcome novelties, until consumer markets made it all but instantaneous. Life became future-oriented and ever more hurried.

But increasingly, the symptoms suggest that that era of human management is more a temporary aberration than a new paradigm. I feel tempted to suggest that when viewed with the benefit of hindsight, the ‘life towards the future’, as Ernst Bloch had it, will be filed in the annals of human history as a rather uncharacteristic and surely untypical episode – a romantic adventure, hotly passionate, but brief.

review: You’re right about the significance of the Lisbon Earthquake. Perhaps the most famous response – and one that echoes your assertion that the response to the earthquake was to take God-forsaken nature under human management – is Voltaire’s Candide. The final line, a riposte to apostles of Panglossian progress, resonates here: ‘We must cultivate our garden.’ It captures well the Enlightenment sense that humanity can emerge from its ‘self-incurred tutelage’, as Kant put it, the sense that through our own reason (and there is/was no higher authority than our own reason!) we can grasp the laws of the natural and social world, and shape the world according to our own rationally chosen ends. Why then in the 21st century, at a time when our ability to ‘manage’ nature, ‘to cultivate our garden’, to ‘live towards the future’ is unparalleled, does the Enlightenment project (if I can call it that) appear as a ‘brief’ interlude?

Bauman: George Steiner once said that the privilege of Voltaire, Diderot, Rousseau, Holbach, Condorcet and their ilk was their ignorance: they didn’t know what we know and can’t forget. Isaiah’s ‘New Jerusalem’ descending – reluctantly and not without resistance – from the heavenly future, will do so in the company of Auschwitz, Kolyma and Hiroshima. All of these were the fruits of our garden’s keen and skillful cultivation.

review: You even liken the progressive relationship to time, and to nature, to a passionate affair. Do you think that, following this affair, we are returning to our long-term relationship with temporality, an older, almost theological-allegorical conception of time, of the fall and apocalypse, of decadence and redemption? After all, from environmentalism to radical Islam, there is no shortage of a sense of the End Times.

Bauman: I repeat what I said before: the future (once the safe bet for the investment of hopes) smacks increasingly of unspeakable (and recondite!) dangers. So hope, bereaved, and bereft of the future, seeks shelter in a once derided and condemned past, the home of superstitions and blunders.

With the options available among time’s offers discredited, each carrying its measure of horror, the phenomenon of ‘imagination fatigue’, the exhaustion of options, emerges. The end of time approaching may be inane, but is surely not unexpected.

Zygmunt Bauman is a sociologist and author, most recently, of Retrotopia, published by Polity. (Order this book from Amazon(UK)).

£1 a month for 3 months

You’ve hit your monthly free article limit.

Support spiked and get unlimited access.

Support spiked – £1 a month for 3 months

spiked is funded by readers like you. Only 0.1% of regular readers currently support us. If just 1% did, we could grow our team and step up the fight for free speech and democracy.

Become a spiked supporter and enjoy unlimited, ad-free access, bonus content and exclusive events – while helping to keep independent journalism alive.

———————————————————————————————————————————–

Exclusive January offer: join today for £1 a month for 3 months. Then £5 a month, cancel anytime.

———————————————————————————————————————————–

Monthly support makes the biggest difference. Thank you.

Comments

Want to join the conversation?

Only spiked supporters and patrons, who donate regularly to us, can comment on our articles.