Long-read

In defence of the masses

Victorian elitism is back. Let’s fight it.

‘There are stupid, ignorant people in every country but their blameless stupidity mostly doesn’t matter because they are not asked to take historically momentous and irrevocable decisions of state’, read an article in Prospect, on the eve of the EU referendum. ‘It’s time for the elites to rise up against the ignorant masses’, read a startling headline in Foreign Policy, post-referendum. ‘Like all fundamentalisms’, noted one Tory Remainer, ‘democratic extremism takes a noble idea, that everyone’s political views should count equally, too far’. Not for decades has the elite felt emboldened to make arguments so brazen, so anti-democratic, so positively 19th century, as they have in the wake of the Brexit vote.

The bald, seething contempt with which journalists, academics and politicians met the British people’s decision to leave the European Union has been remarkable. Though often dressed up in defences of representative, parliamentary democracy, against the alleged instability of direct democracy and plebiscites, the message has been clear: the masses are too stupid, too emotional, too morally ill-equipped to play a serious role in political life. ‘Letting policies with wide ramifications be settled by the emotions of a moment will only ensure that popular sentiment holds sway over informed decision-making’, writes former United Nations grandee and Shashi Tharoor (my italics), without a glint of self-awareness.

The necessity of having a cool-headed elite to temper the will of the masses, and insulate politics from the people, has been argued for plainly, even by those who would consider themselves radical and progressive. In an interview with Open Democracy, philosopher Slavoj Zizek slammed the referendum, arguing instead for the ‘appearance of a free decision, discretely guided’ by the elite – an ‘invisible state, whose mechanisms work in the background’. Elitism, technocracy, soft tyranny, even, are being presented as necessary correctives to the ignorance of the masses: ‘Perhaps’, opined a US academic, ‘the UK’s leaders owe it to the people to thwart their expressed will’.

It would be tempting to see this as a blip, an emotional outpouring from a spurned elite hell-bent on maintaining the status quo. The shamelessness with which arguments against democracy, against the people, have been put forward feels genuinely astonishing and new in an era in which those who rule feel, at the very least, obliged to tiptoe around us, rather than greet our arguments and passions head-on. But history shows us there is nothing surprising to the elite’s response to the Brexit vote. Looking back over the centuries-long battle for democracy, it’s clear that anti-democratic arguments have always been startlingly similar in character.

As with the Brexit vote, it is the moments in history when the public make their presence felt, when they threaten to upend the political order, that the fury of the elites comes into play. In 1774, when Edmund Burke addressed a meeting in Bristol, the idea that the expertise of the parliamentarian always trumps the will of his constituents was a given. ‘To deliver an opinion, is the right of all men’, he said. ‘But authoritative instructions; mandates issued, which the member is bound blindly and implicitly to obey, to vote, and to argue for, though contrary to the clearest conviction of his judgment and conscience… these are things utterly unknown to the laws of this land.’ Yet, over the course of the 19th century, as the demand for suffrage among the working classes in Britain grew louder, the gloves came off.

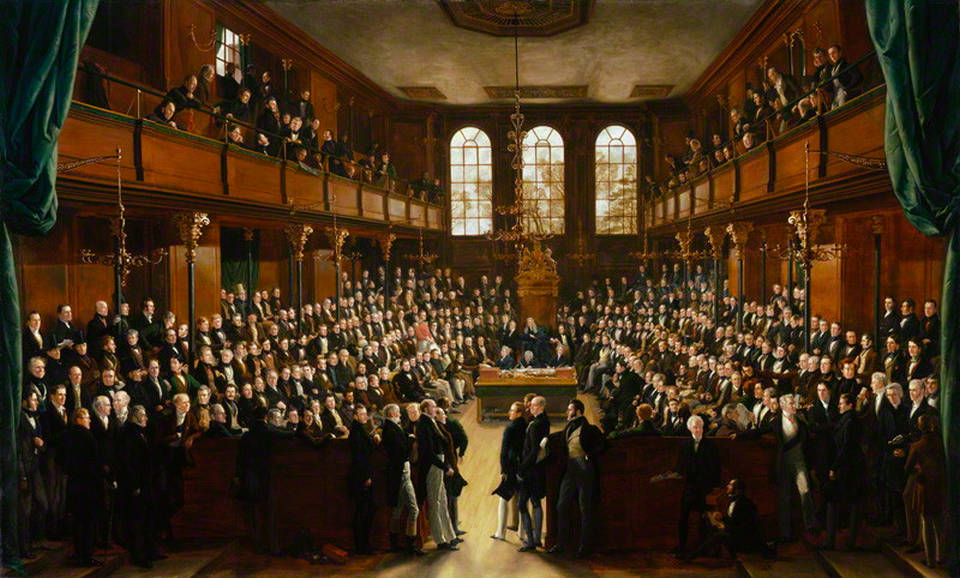

‘I say, it is the everlasting privilege of the foolish to be governed by the wise; to be guided in the right path by those who know it better than they. This is the first “right of man;” compared with which all other rights are as nothing’, wrote Thomas Carlyle in 1850. He was writing in the wake of the Chartist rebellion, a working-class movement demanding the enfranchisement of men in Britain. Indeed, it was during the 1830s and 1840s – when the Chartists addressed meetings of thousands of working people across the country, mounted insurrections against the state, and presented parliament with petitions adorned with more signatures than the democratic mandate of the entire House of Commons – that the kind of elitist arguments we hear today find their clearest echo.

Demagogues

In 1842, the Chartists presented their second petition to parliament, bearing 3.3million signatures. It was rejected by a vote of 287 to 49. But what is most striking about the speeches made against it is the refusal to believe that it represented the true will of the people at all. Whig MP Thomas Babington Macaulay delivered perhaps the most memorable condemnation of the Charter, insisting that the brutalised poor were being manipulated by Chartist demagogues:

‘Imagine a well-meaning laborious mechanic, fondly attached to his wife and children. Bad times come. He sees the wife whom he loves grow thinner and paler every day. His little ones cry for bread, and he has none to give them. Then come the professional agitators, the tempters, and tell him that there is enough and more than enough for everybody, and that he has too little only because landed gentlemen, fundholders, bankers, manufacturers, railway proprietors, shopkeepers have too much. Is it strange that the poor man should be deluded, and should eagerly sign such a petition as this?’

How much that chimes with the post-Brexit fallout, in which the ‘dog whistles’ of Nigel Farage, and the crowd-pleasing buffoonery of Boris Johnson, was said to have whipped up the passions of Britain’s feckless poor.

Macaulay couches his rejection of the petition in the language of conscience. The Chartists’ demand for suffrage, alongside their agitation against scarcity and inequality, were seen by the elite as setting society on the road to ‘general anarchy and plunder’. In the end, the poor, he opined, were unknowingly acting against their best interests, and thus it was the elite’s responsibility to protect them from themselves. ‘Have I any unkind feeling towards these poor people?’, he said. ‘No more than a humane collector in India has to those poor peasants who in a season of scarcity crowd round the granaries… I would not give up the keys of the granary, because I know that, by doing so, I should turn a scarcity into a famine.’ The masses were, in his view, demanding ‘the liberty to destroy themselves’.

Education

Then, as today, the ignorance of the uneducated masses was presented as a fact of life we would be wrong to ignore. Macaulay implied he was only averse to ‘universal suffrage before there is universal education’. Similarly, John Stuart Mill insisted that, while being poor alone shouldn’t bar people from the franchise, certain educational tests should be enforced to ensure that parliament is governed by reason rather than blind passion. ‘No one but a fool’, he wrote in his 1861 tract Representative Government, ‘feels offended by the acknowledgement that there are others whose opinion, and even whose wish, is entitled to a greater amount of consideration than his’. To this end, Mill advocated plural voting for graduates and professionals, and an aptitude test for the working classes.

The claim that all the masses lacked was education ignores the fact that politics is about more than facts. In the same way values and principles can’t be discovered in a laboratory, so too politics can’t be conducted on the level of expertise. As the Chartists argued, the masses were not only better versed in politics than the elite gave them credit for, but those at the coalface were in many ways better equipped than the aloof elite to reckon with the problems of society. ‘We have met with untutored mechanics – men who made no pretensions to learning – whose views on political topics were clearer, and their sentiments more just, than nine-tenths of the right honourables who sign MP after their name’, read an article in the Chartists’ Circular.

What’s more, as the battle for universal suffrage raged on into the 20th century the education argument was shown up as the snobby excuse that it was. As John Carey notes in his seminal 1992 book The Intellectuals and the Masses, the introduction of universal education at the end of the 19th century, and the explosion of literacy among the working classes, did nothing to temper the elite’s disdain. Daily mass newspapers, the rise of which were so crucial to the emergence of mass politics, were, in the words of TS Eliot, merely affirming the public’s status as a ‘prejudiced, complacent and unthinking mass’. DH Lawrence, meanwhile, openly declared that ‘the great mass of humanity should never learn to read and write’.

Eugenics

Between 1884 and 1928 a series of slow, plodding reforms – formulated with the hot breath of the masses on parliament’s back – brought universal suffrage to Britain. Yet the contempt with which the elite held the masses only grew. Indeed, the rise in popularity of eugenics – across left and right – saw the franchise being extended at precisely the same time that intellectuals fantasised about thinning out the herd. Co-founder of the Fabian Society, Beatrice Webb, believed eugenics was essential to building a just and thriving society. Fellow Fabian and science fiction author HG Wells put it in even starker, misanthropic terms: ‘We cannot make the social life and the world peace we are determined to make, with the ill-bred, ill-trained swarms of inferior citizens that you inflict upon us.’

In the rise of eugenics, the elite loathing of mass society found its darkest expression. As Dennis Sewell has noted, the introduction of the Mental Incapacity Act in 1913 led to 40,000 men and women being incarcerated without trial, ‘having been deemed to fall into various specious categories such as “feeble-minded” and “morally defective”’. ‘Theoretically’, Sewell writes, ‘such measures were targeted at the mentally handicapped, but diagnosis of mental incapacity was applied somewhat loosely, and the act was frequently used as an instrument of oppression against the chronically poor’. Meanwhile, Carey notes, the likes of DH Lawrence, WB Yeats and George Bernard Shaw fantasised openly about ‘the extermination or sterilisation of the mass’ – the image of the gas chamber becoming a kind of ‘imaginative refuge for early 20th century intellectuals’.

Over the past two centuries, the elite’s disdain for democracy has flared in reaction to the masses making their presence felt – from parliament’s dismissal of the Chartists as the dupes of demagogues to the 20th-century depiction of the verminous masses as a threat to civilisation itself. It is precisely that old contempt we have seen being played out in a new way in reaction to the Brexit vote. The familiar appeals to public ignorance and gullibility, the calls for calm governance over public passion, the idea that demagogues are warping the poor, the notion that politics is best done by experts and elites rather than by the plebs — all these arguments have come back, reflecting an age-old revulsion with the public’s desire to shape politics, to be something more than the playthings of elites and the objects of history.

The rejection of democracy is, in the end, a rejection of the masses and our capacity to shape and remake our world. In the wake of the referendum, we may not be on the brink of mass sterilisation, a rescinding of the franchise or a pogrom. But we can be sure that the elite disdain for democracy – its disdain, that is, for us – is alive and well. Fighting against this, and demanding that the democratic will of the people be respected and in fact expanded into more areas of political life, should form the basis of any vision of a new Europe.

Tom Slater is deputy editor of spiked. Follow him on Twitter: @Tom_Slater_

To enquire about republishing spiked’s content, a right to reply or to request a correction, please contact the managing editor, Viv Regan.

Comments

Want to join the conversation?

Only spiked supporters and patrons, who donate regularly to us, can comment on our articles.