Long-read

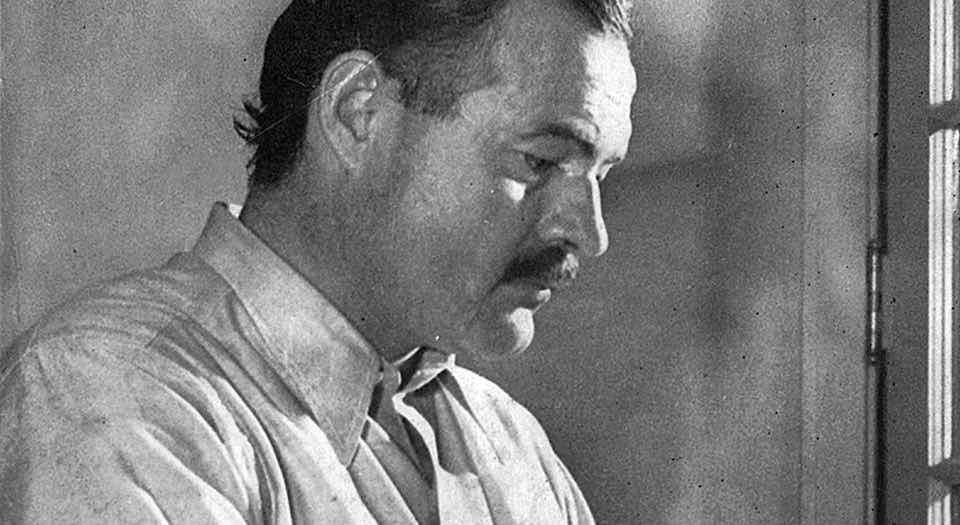

Getting into Hemingway’s head

A new book explores the effect chronic alcoholism and head trauma had on the writer’s late work.

Want to read spiked ad-free? Become a spiked supporter.

On the morning of 2 July 1961, Ernest Hemingway took his favourite shotgun and shot himself in the head at his home in rural Idaho. He had finally done it. He had threatened suicide, described the suicides of others and even play-acted it with empty guns. He had been talked out of suicide, and physically restrained from doing it, twice before. Dogged by declining health, difficulty in writing and now a chronic writer’s block, Hemingway chose death. He was haunted by the knowledge that his father had shot himself. Two of Hemingway’s siblings would later commit suicide, with suicide being the suspected cause of death for another sibling. Suicide was a hereditary risk for the Hemingways.

In Hemingway’s Brain, Andrew Farah, a clinical psychiatric practitioner, has analysed the causes of the mental decline that precipitated Hemingway’s suicide and has come up with a new diagnosis.

Born in 1899, Hemingway lived a life that was physically precarious. Sometimes due to accident, sometimes by placing himself in dangerous situations, Hemingway courted danger and death. This was in his character and it underpinned a heroic persona that found its way into his writings. As a boxer, deep-sea angler, big-game hunter, trainee bullfighter, war correspondent and hard-drinker, Hemingway lived a life that transcended the macho and became epic.

During the First World War in northern Italy, Hemingway was wounded by a mortar explosion and hit by machine-gun bullets. He suffered shrapnel and bullet wounds and experienced concussion. In 1928 he was struck by a falling skylight and suffered a head injury. In the middle of a blackout in London during the Second World War he suffered another head injury in a car crash. While acting as a press reporter-cum-irregular soldier, Hemingway was blown from a car by a German anti-tank gun, landing on his head. He suffered double vision, memory loss and impaired speech. In 1950 he added to the list two more spectacular head injuries: the first in another car crash, the second in a boating accident. In 1954 he barely escaped a light-aircraft crash in Africa, sustaining more head injuries in the process. Additionally, Hemingway would have suffered some heavy blows to the head during his school football career and his boxing bouts, both early in his life.

These six documented head traumas had a grave cumulative impact on Hemingway’s health. Hemingway described classic symptoms of post-concussive syndrome in conversation and letters: headaches, dramatic temporary sensory alteration, memory loss and impaired use of language. He was also newly prone to mood swings, which were exacerbated by excessive alcohol intake.

Farah makes a decisive break with previous authors, who have tended to diagnose Hemingway with bi-polar disorder:

‘”Bipolar” symptoms can be fully explained by the illness of alcoholism. What biographers have termed “bipolar” or “manic-depressive” disorder would be more accurately termed “alcohol-induced mood disorder”. On paper, the symptoms of alcoholism – mood swings, volatility, depression, erratic sleep and insomnia, self-destructiveness, and even psychosis – are also hallmarks of bipolar illness. Contrary to popular myth, Hemingway never had a manic episode, and his name should be erased from every list of “famous bipolar patients”.’

According to the alcohol intake Hemingway described and what was recorded by others at the time, Hemingway would have met the description of a functioning alcoholic. Farah describes the effects of alcohol and brain trauma as a destructive tag-team accelerating Hemingway’s cognitive and mood problems into chronic traumatic encephalopathy (CTE) – a form of dementia commonly experienced by boxers and American football players. (The American football league has recently paid a $765million liability settlement to former players who have suffered brain damage due to head trauma.)

Farah explains that dementia patients often suffer unprecedented and very elaborate paranoid fantasies. Hemingway experienced bouts of paranoia in his last years. Trivial (and even invented) transgressions became obsessions that drove the writer to distraction, even when others (even officials) assured him that no legal or financial penalties were due. Farah quotes letters in which Hemingway displays paranoid delusions and he gives examples of unprovoked rages and instances of behavioural disinhibition in later life.

Written in his last years, Hemingway’s last unfinished manuscripts had to be drastically edited down for posthumous publication. Looking at the original unedited manuscripts, Farah detects evidence of dementia. Hemingway’s famously curt precision has deteriorated into wordy, repetitive tales that are narratively confused and incomplete. The notably sour portrayals of early acquaintances in A Moveable Feast might be partly the result of disinhibition. (Even Hemingway acknowledged that he had gone too far.) While authors do alter style and experiment, it seems clear that Hemingway had serious problems at the time the manuscripts were being worked on. Despite some crisp dialogue and flashes of evocative description, Hemingway was not happy with these late texts, considering them unfinished, but he could not see how to improve or finish them. While it is important to keep published texts close to the author’s intentions, Hemingway’s last novels present an insoluble problem for editors, critics and readers. Even great writers have failures.

In 1960, Hemingway was admitted to the Mayo Clinic (under a false name) and doctors performed a battery of tests on him. Dementia caused by CTE was not a recognised condition at the time and the closest fit doctors could find was ‘manic-depression’ (or bi-polar disorder). An important – and often effective – treatment for manic-depression was electro-convulsive therapy (ECT). Hemingway was given a course of 15 sessions, which did not noticeably improve his condition, and was discharged.

The ECT apparently caused a relentless writers’ block, which led Hemingway to spend hours at the typewriter unable to write more than a sentence or two. He was unable to settle upon a title for his new novel. Facing this impassable mental block, Hemingway contacted his publisher to tell them he could not finish the novel. A return to the Mayo Clinic and a further round of ECT failed to help and intensified short-term memory loss. Farah suggests that anxiety about ECT added to Hemingway’s distress.

By 2 July 1961, Hemingway felt he had reached the end of the line.

Diagnosis at a distance is tricky. However, based on plentiful sources of evidence, Farah makes a persuasive case for the diagnosis of CTE caused by brain injury and alcoholism. Hemingway’s Brain does not diminish Hemingway; it makes the author’s late writings appear more comprehensible – without undercutting their charm and power.

Alexander Adams is an artist and writer. His latest book, Letter About Spain, is published by Aloes.

Hemingway’s Brain, by Andrew Farah, is published by University of South Carolina Press. (Order this book from Amazon(UK)).

Picture by: Wikimedia Commons.

Who funds spiked? You do

We are funded by you. And in this era of cancel culture and advertiser boycotts, we rely on your donations more than ever. Seventy per cent of our revenue comes from our readers’ donations – the vast majority giving just £5 per month. If you make a regular donation – of £5 a month or £50 a year – you can become a and enjoy:

–Ad-free reading

–Exclusive events

–Access to our comments section

It’s the best way to keep spiked going – and growing. Thank you!

Comments

Want to join the conversation?

Only spiked supporters and patrons, who donate regularly to us, can comment on our articles.