The murder of Mayakovsky’s poetry

A Soviet crime — the neglect of their greatest poet — must be avenged.

Want unlimited, ad-free access? Become a spiked supporter.

‘Biographers are amateur private detectives’, Roman Jakobson once wrote. If so, there are few juicier cases than Vladimir Mayakovsky. For even his death presents a double murder: the suicide of the man and the annihilation of his poetry. The crime scene remains intact – preserved for us by Pasternak. The corpse lies, alone in a room, with a bullet through the heart. The murder weapon – a Mauser pistol – was provided by an agent of Stalin’s secret police. The suicide note is a startling poem – with a new pun.

‘Between eleven and twelve the ripples were still circling around the shot’, wrote Pasternak, on 14 April 1930. ‘The news rocked the telephones, blanketed faces with pallor. He lay on his side with his face to the wall, sullen and imposing, with a sheet up to his chin, his mouth half open as in sleep. Haughtily turning his back on all, even in this repose, even in this sleep, he was stubbornly straining to go away somewhere… death had arrested an attitude which it almost never succeeds in capturing. This was an expression with which one begins life but does not end it. He was sulking and indignant.’

At eight o’clock that evening, Mayakovsky has his skull drilled so that his brain could be preserved, as an organ of genius, for future generations in the USSR. When weighed, it was found to be 360 grams heavier than Lenin’s, ‘which meant a bit of a headache for the ideologues of the Brain Institute’. An inquest into the cause of death was launched immediately. It found that the poet had shot himself ‘for personal reasons’. But in this fascinating, long overdue biography, Bengt Jangfeldt presents a more complex solution.

Cause of death? Frustrated poetry.

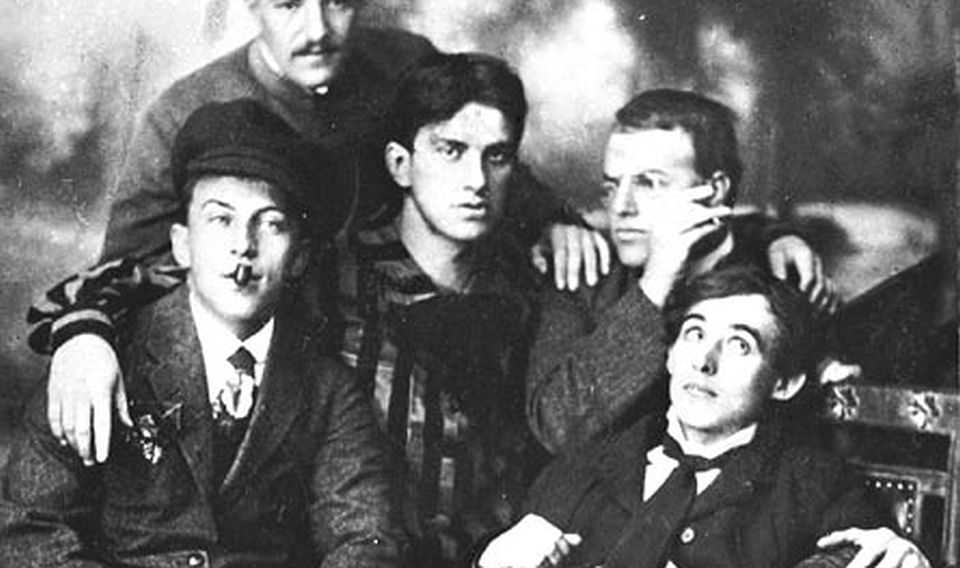

Born in rural Georgia in 1893, Mayakovsky had an innate capacity for memorising and reciting verse. He only began writing it, as a teenager, when jailed for Bolshevik agitation. He served five months in solitary confinement, in Moscow’s notorious Butyrka prison, reading Byron, Shakespeare and Tolstoy ‘without great enthusiasm’. On release, Mayakovsky is said to have leapt out, a fully formed poet — like Pallas Athena from the brain of Zeus. In 1912, already obsessed with creating a new kind of poetic language, capable of articulating the coming revolution, he joined the Futurist movement and started touring Russia, reading his poetry to anyone who would listen (and many who wouldn’t). One early performance in Kiev was attended by ‘the governor-general, the chief of police, eight police commissars, 16 assistant commissars, 25 police supervisors, 60 police constables…. 50 mounted police were outside.’ Mayakovsky was delighted. ‘What poets, apart from ourselves, have been honoured with such a state of war?’, he demanded. ‘Ten policemen for every poem read. That’s what I call poetry.’

Already, Mayakovsky was a complex character. An ambidextrous cardsharp, who took losing as a personal insult; a proletarian agitator, who dressed like a dandy; a germ-fearing hypochondriac, smoking 100 cigarettes a day; a lady-killer with rotten teeth, causing a string of abortions wherever he went. He transformed perfectly successful romances into desperate and blistering love lyrics. Massive and overbearing, at six foot three, always beating out the rhythm of his verse with his steel toe caps and a cane, he made constant jokes, but rarely laughed at them. He had a shaven head, the demeanour of a ‘hooligan’, and when deprived of an audience he turned out to be neurotic and very gentle. Even his name, from the Russian word for ‘Lighthouse’, sounded like he’d made it up. His living arrangements were also unorthodox. From around 1915, until shortly before his death, he lived in a complicated ménage a trois, with his muse, Lilya, and her husband, the critic Osip Brik.

The sheer, shocking inventiveness of Mayakovsky’s poems is nigh impossible to translate. ‘I always put the most characteristic word at the end of a line and find for it a rhyme at any cost’, Mayakovsky explained in his essay ‘How To Make Verse’. ‘As a result, my rhymes are almost always out of the ordinary and, in any case, have not been used before me and do not exist in rhyming dictionaries.’ His poems fizz with ‘grammatical deformations, bizarre inversions, neologisms and puns’. According to one Russian critic, the English equivalent of a conservative Mayakovskian rhyme would be Browning’s ‘ranunculus’ with ‘Tommy-make-room-for-your-uncle-us’. What does come across in English, however, is the brilliance and brutality of his metaphors. ‘My poems’, he explains, ‘Jump out / like mad gladiators / ‘Kill!’ / they cry.’ In one, he invites the sun to have tea with him; in another, he inserts it, like a monocle, in his gaping eye. He orders firemen to climb into his heart, to put out an inferno. He complains he was ‘sired by Goliaths – / I, so large, so unwanted’, but says he is so tender, as a lover, that he is not a man ‘but a cloud in trousers’.

Before the Russian Revolution, Mayakovsky anticipated it. When it dawned, he was determined to lay his talent at its service – creating posters and advertising jingles for ROSTA, the state news agency. For a decade, Mayakovsky claimed, ‘The working class / speaks / through my mouth. / And we, / proletarians, / are drivers of the pen.’ He appalled Lenin with his panegyric poem ‘150,000,000’ (‘stupid, stupid beyond belief… should be horsewhipped for Futurism’) but amused him with his satirical take on Soviet bureaucracy (‘in his poem he ridicules all conferences and pokes fun at Communists who simply attend one conference after another. I can’t comment on the poetry, but as far as the politics are concerned, I can guarantee that he is absolutely correct.’)

In the early years of the Soviet regime, Mayakovsky enjoyed artistic freedom, his praise of the Bolshevik vision entirely self-imposed. He was able to churn out poems in praise of the Soviet state, but also astonishing, free-flowing lyrics, such as ‘I Love’ and ‘About This’. But, from 1926 onwards, when Stalin began his inexorable rise, Mayakovsky felt under pressure to write politically pure verse. His attempts, such as ‘The Saboteur’ – about the Shakhty trial – and ‘The Story of the Smelter Ivan Kozyrov about How He Moved into a New Apartment’ verge on the abysmal. ‘During one of our meetings, Mayakovsky, as was his custom, read me his latest poems’, wrote Roman Jakobson. ‘Considering his creative potential I could not help comparing them with what he might have produced. “Very good”, I said, “but not as good as Mayakovsky”.’

Privately, Mayakovsky worried that he was ‘finished’ as a poet: ‘As the years go by, / you wear out / the machine of the soul. /And people say: / “A back number, / he’s written out, / he’s through! / There’s less and less love, / and less and less daring, / and time is a battering ram / against my head. / Then there’s amortization, / the deadliest of all; / amortization / of the heart and soul.’

He travelled extensively, to Germany, France, Mexico and America, meeting Picasso, Cocteau and attending Proust’s funeral. While in New York, he fathered an illegitimate child. On his return, he turned his attentions to the stage, writing his greatest satire, The Bedbug. That same year, 1928, his poetry began to gush forth once more – in the most inconvenient manner possible. Women had always been crucial to Mayakovsky’s lyricism, and when he met Tatyana Yakovleva, a leggy White Russian émigré in her early twenties, with a ‘perfect pitch’ for poetry, her impact was immediate. In ‘Letter from Paris to Comrade Kostrov on the Nature of Love’, which he knew would drop ‘a bomb’ on his audience back home, Mayakovsky described how, ‘Love has inflicted / on me / a lasting wound – I can barely move… / love / tells us, humming / that the stalled motor / of the heart / has started to work / again.’

Back in Moscow, Lilya Brik — the woman to whom Mayakovsky had dedicated his poems for more than a decade — was not best pleased at being replaced as the great man’s muse. And neither were her close friends in the security services impressed that their ‘iron poet’ was, all of a sudden, writing violent, all-consuming love poems to a bourgeois beauty, ‘all inset in furs / and beads’. As early as 1920, the Briks were known as informants, when an anonymous note was pinned to their door: ‘You think that Brik lives here, the noted linguist? / Here lives an interrogator and a Chekist.’ In the late 1920s, the Briks were able to acquire exit visas for foreign travel at a time they were denied to nearly every other citizen in the Soviet Union. Including Mayakovsky, who, in 1929, was refused permission to return to Paris, where he had hoped to marry Tatyana.

It is at this point that Jangfeldt’s book becomes both horrifying and utterly compulsive, as it plunges headlong into the poet’s final days. It is as if Lilya Brik, the Soviet Writers’ Union (RAPP) and Stalin’s secret police (the OGPU) all compete, to see who can polish a bullet fastest, for Mayakovsky’s gun. First, Jangfeldt implies, the OGPU stuffed Mayakovsky’s poetry readings full of detractors, to ask him questions such as: ‘Mayakovksy, we know from history that good poets tend to come to a bad end. Either they’re murdered or… When were you thinking of shooting yourself?’ Then RAPP ensures that a retrospective of 20 years of Mayakovsky’s work is a dismal, barely attended failure. And Lilya, keeping track of Tatyana’s every movement in Paris, through her sister and agents abroad, informs Mayakovsky that Tatyana has married a viscount, in the cruellest and most public way possible. Disappointed, depressed and prone ‘to a quite gratuitous gloom’, Mayakovsky began work on yet another dangerous poem, explaining: ‘Agitprop / sticks / in my teeth too / and I’d rather / compose romances for you – / more profit in it and more charm. / But I / subdued / myself, / setting my heel / on the throat / of my own song.’

On New Year’s Eve, 1929, Lilya Brik threw Mayakovsky what might well be the ghastliest party in the annals of world literature. The guest list is filled with political informants, the festivities are fuelled by 40 bottles of champagne, snow-chilled in the bath, and Mayakovsky spends most of the evening sitting alone in a corner. When his old friends, Pasternak and the critic Shklovsky, gatecrash in the early hours of the morning, Mayakovsky won’t even look at them. ‘He doesn’t understand’, Mayakovsky said, referring to Pasternak. ‘He’d better leave. He thinks it’s like a button that you rip off today and sew back on tomorrow… They rip people away from me so that my flesh comes away too.’

Four months later, Mayakovsky was dead. That day, too, Jangfeldt records precisely, exactly like a detective, picking through evidence. The night before Mayakovsky had invited friends to dinner – and none of them had turned up. He had sat drinking alone, had slept very little. In the morning, which was bright and sunny, he met with his girlfriend, a young actress called Nora. He asked her not to leave him, to rehearse her latest play, and, when she did, he shot himself through the heart. The Briks were abroad, sightseeing in Amsterdam. On Lilya’s return, she decided Mayakovsky had just lost the final round in a game of Russian roulette he had been playing with himself, on and off, for two decades. ‘He shot himself in Nora’s presence’, she wrote. ‘But she bears as much blame as an orange peel when one slips on it, falls over and dies.’

Mayakovsky’s fellow poets disagreed: they thought he had been driven to death – by the torrent of his own poetry. ‘I had always thought’, said Pasternak, ‘that Mayakovsky’s innate talent would explode one day, that it would be forced to blow up these storehouses of chemically pure nonsense, dreamlike in its meaninglessness, which he has voluntarily decked himself out in until he became unrecognisable.’ Or, as Marina Tsvetaeva put it, so succinctly: ‘For 12 years in a row Mayakovsky the human being tried to kill Mayakovsky the poet within himself; in the thirteenth year the poet stood up and killed the human being.’

But if the poet within killed the man, to save the poetry, a far greater tragedy than Mayakovsky’s suicide occurred afterwards. Five years after his death, Lilya Brik wrote to Stalin, requesting assistance in getting Mayakovsky’s ‘Collected Works’ published. Stalin’s response must have delighted her — but it condemned Mayakovsky’s poetry to oblivion outside the Soviet system. ‘Mayakovsky was and remains the best and the most talented poet of our Soviet epoch’, Stalin declared. ‘Indifference to his memory and his work is a crime.’ From then on, Mayakovsky’s ‘storehouses of chemically pure nonsense’ were forcefed to hundreds of millions across the USSR while his real achievement, his personal lyrics, was written out of history. Then, when the Soviet Union fell, Mayakovsky’s reputation collapsed with it. Today, he is not celebrated as the author of some of the most startlingly original verse in the Russian language, but as a versifier of totalitarianism. His name may still be emblazoned on street signs, a Moscow metro station and a nightclub in Omsk, but in post-Communist Russia, just as here in the West, his poetry is hardly read at all.

That is the greatest crime his biographer must solve – and, by reading this book, you can help close the case.

Emily Hill is a writer based in London. Visit her website here.

Mayakovsky: A Biography, by Bengt Jangfeldt, is published by University of Chicago Press. (Order this book from Amazon(UK).)

You’ve hit your monthly free article limit.

Support spiked and get unlimited access.

Support spiked and get unlimited access

spiked is funded by readers like you. Only 0.1% of regular readers currently support us. If just 1% did, we could grow our team and step up the fight for free speech and democracy.

Become a spiked supporter and enjoy unlimited, ad-free access, bonus content and exclusive events – while helping to keep independent journalism alive.

Monthly support makes the biggest difference. Thank you.

Comments

Want to join the conversation?

Only spiked supporters and patrons, who donate regularly to us, can comment on our articles.