Working-class kids should be challenged, not tested

Tests for four-year-olds will only entrench low expectations.

Want to read spiked ad-free? Become a spiked supporter.

Of all the controversial policy directives forced upon schools in recent years – and there have been many – plans to introduce ‘baseline assessments’ must win the prize for being the least popular of all. The image of little four-year-olds being yanked away from play, squeezed into school uniforms and corralled into taking formal tests just days after starting school is surely only something the most child-hating of Gradgrinds could support.

Yet from this September, every child starting school in England will be assessed according to the reception baseline. Their skills in reading, numeracy and writing, as well as their social and emotional development, will be measured, scored and recorded. In fact, the development of each child in all of these areas will be combined into just one score. Complex children with emerging personalities and preferences that change daily will be reduced to one single number.

This figure, the Department for Education (DfE) tells us, will not be used to grade and rank pupils, nor will it be used to monitor individual progress. Instead it is designed to hold schools to account. When children leave primary school seven years later, the reception baseline score will be used to ‘calculate how much progress they have made compared to others with the same starting point’. Baseline assessments provide the DfE with a means of measuring school progress that takes account of ‘schools with challenging intakes’.

Unsurprisingly, critics of baseline testing are numerous. Commentators have been vocal in condemning government ministers who, seemingly lacking any sense of what education is for, substitute measuring what children can and can’t do for actually teaching them anything. Unfortunately, many of the critics of baseline assessments similarly lack a sense of purpose when it comes to teaching; worse, they fail to recognise that this initiative is built on the very assumptions about education they themselves have been pushing for decades.

Much of the reaction against baseline assessments has focused on the disruptive nature of implementing the tests in the first few weeks of the school year and the additional stress this will put on children. A report commissioned by the two biggest teachers’ unions, emotively titled They are children… not robots, not machines, argues:

‘The start of school is a precious and important time for our children. Get it right and the seeds are sown for a love of learning that can carry on through school and into adulthood. Get it wrong and the scourge of low self-confidence and disaffection for school can set in, blighting a child’s life chances.’

The idea that there is a small but all important window of opportunity to set children on the correct learning trajectory taps into current beliefs about infant determinism. It assumes that what happens in the early years of a child’s life is all important in deciding his or her future. Of course, no one wants children to be miserable when they start school. But in reality many children do have problems settling in for all kinds of reasons; plenty of four-year-olds are simply not ready for school and would far rather be at home. To suggest that such children are doomed and their life chances blighted is plain ridiculous. There is no evidence to show that children who have a disrupted and unhappy start to school are not still learning, nor that an inspiring teacher and an exciting curriculum years later can’t instill a love of knowledge.

Baseline assessments won’t put an end to childhood as we know it. No child will be expected to sit pen-and-paper tests. Instead they will be observed taking part in various tasks and teachers will be expected to complete checklists recording what they can do. Reception-class teachers already have a very good handle on what their pupils are capable of doing – they would not be able to do their jobs otherwise. Children in nursery and reception classes are extensively observed and assessed as part of the Early Years Foundation Stage. Moving away from all forms of assessment in the first few years of school would free teachers to think about what it is they want young children to know and give them back the time to teach.

Yet the critics of baseline tests cannot make the case against all forms of assessment. At best, they argue that the pressure to complete a new set of observations in a much shorter timeframe will make the results unreliable and will fail to provide an accurate reflection of children’s abilities. The most vocal critics of baseline assessments cannot argue against testing four-year-olds because they are often the very same people who provided the rationale that underpins baseline assessments. The DfE claims baseline assessments are shaped by the principle that ‘measures of progress should be given at least as much weight as attainment’. And this principle – that progress is just as important (or indeed more important) than what a child actually knows when he or she leaves school – is exactly what critics of recent government education policies have been arguing for years.

The leaders of the teaching unions, people like Mary Bousted, have long claimed that family background is the biggest factor in determining a child’s educational progress, and that ‘a narrow academic curriculum’ is alien to the lives of children living in poverty. In other words, they claim that children from poor families cannot be expected to learn the same material, at the same rate and to the same standard, as kids from middle-class homes. So entrenched is this belief that they argue school performance is only a measure of the prosperity of the intake. They counter that a better indicator of a school’s success is the ‘value added’, or the progress pupils make. In practice, this means children can leave school knowing very little, but as long as they started knowing even less, then the school they attended can be judged to be successful.

The belief that success at school is determined more by family income than by anything teachers do holds back working-class kids who are patronisingly rewarded for making progress rather than challenged to push themselves to achieve as much as their wealthier peers. Teachers need to have high academic expectations of all their pupils and judge them all according to the same standard.

Baseline assessments are a terrible idea for many reasons. There are rumours that the DfE may respond to pressure and change the format of such tests before their introduction in September. But if we are truly interested in the education of all children then opposing baseline assessments is not enough. We need to go further and reject the whole notion that the aim of a school is the ‘value added’. We need to argue that rather than ‘progress’ being sufficient, all children should have an equal entitlement to a challenging and inspiring knowledge-rich curriculum, whatever their family circumstances. Nothing should justify teachers having lower expectations of children from poorer backgrounds.

Joanna Williams is education editor at spiked. Her new book, Academic Freedom in an Age of Conformity: Confronting the Fear of Knowledge, is published by Palgrave Macmillan UK. (Order this book from Amazon UK and Amazon (USA).

Who funds spiked? You do

We are funded by you. And in this era of cancel culture and advertiser boycotts, we rely on your donations more than ever. Seventy per cent of our revenue comes from our readers’ donations – the vast majority giving just £5 per month. If you make a regular donation – of £5 a month or £50 a year – you can become a and enjoy:

–Ad-free reading

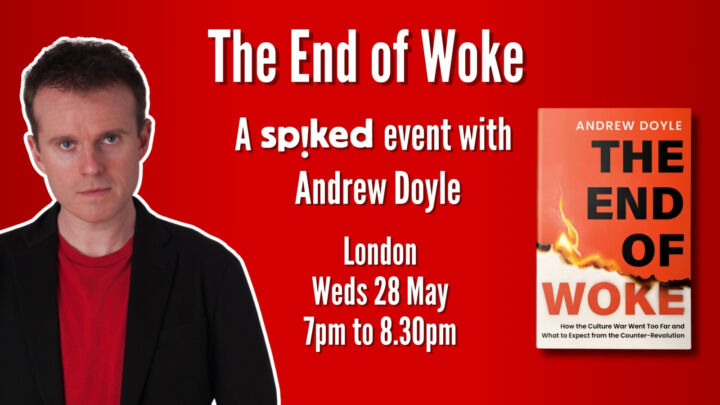

–Exclusive events

–Access to our comments section

It’s the best way to keep spiked going – and growing. Thank you!

Comments

Want to join the conversation?

Only spiked supporters and patrons, who donate regularly to us, can comment on our articles.