Woolwich: butchery is not a thought crime

How the court managed to turn the murderers of Lee Rigby into martyrs.

Want unlimited, ad-free access? Become a spiked supporter.

The bloody public murder of Private Lee Rigby outside Woolwich army barracks last May was a rare act of frenzied brutality which most will accept warranted harsh punishment. So why, when sentencing the two killers to life on Wednesday, did the court feel compelled to insist that it was imposing such long sentences because the homicidal Islamists hacked the soldier to death ‘in order to advance your extremist cause’, as if trying to decapitate a man in a London street was not crime enough?

As Brendan O’Neill pointed out on spiked amid the immediate panicky political and media response to the killing, the Woolwich atrocity was ‘a knife crime, not an act of war’ carried out by two deluded loners rather than an invading army. The danger in treating it as something more is that you can end up ‘doing the terrorists’ dirty work for them’, endorsing their self-aggrandising self-image as terrifying jihadist soldiers threatening our society.

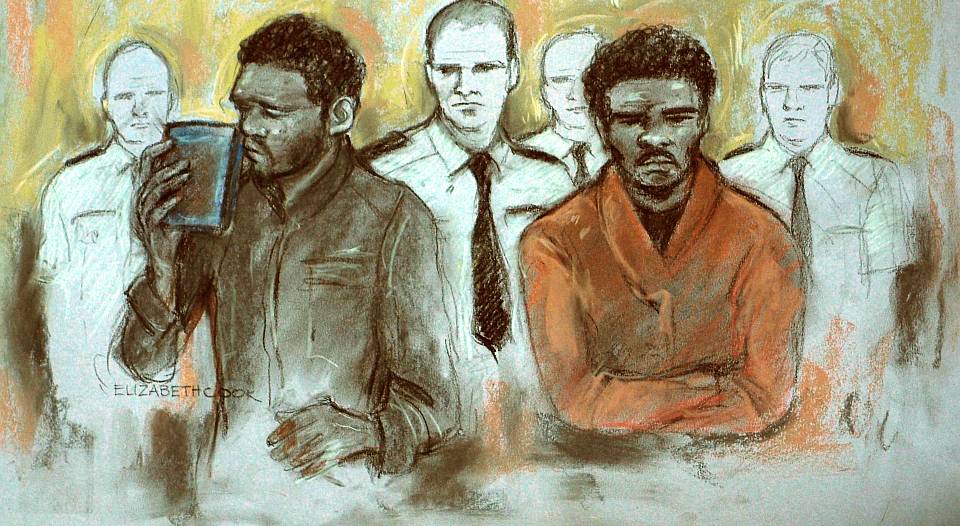

The Old Bailey sentencing hearing this week sounded like a case in point. At every turn, the prosecutors and the judge were keen to emphasise the extremist political character of the murderous assault. Prosecution QC Richard Whittam argued that both Michael Adebolajo and Michael Adebowale should receive whole-life tariffs (meaning they would never be released from prison), not only because of ‘the severity of their crime’ but crucially because of ‘its political motivation’. The judge, Mr Justice Sweeney, imposed a whole-life term on Adebolajo and a minimum 45-year tariff on Adebowale because they had murdered ‘a solider in public daylight’ in order ‘to advance your extremist cause’. After the hearing, Sue Hemming, head of special crime and counter-terrorism at the Crown Prosecution Service, told the media that the whole-life term was justified in these circumstances, because ‘not only was the attack brutal and calculated’, but more importantly ‘it was also designed to advance extremist views’.

During the trial itself, Adebolajo had caused a storm by admitting that he killed Private Rigby yet insisting that this was not murder because he was a ‘soldier of Allah’ engaged in a war against Britain on behalf of Muslims everywhere. The judge felt moved to advise the jury, presumably with a straight face, that this bizarre claim was not a legitimate defence to a charge of murder under English law. Yet weeks later, at the sentencing hearing, all of the legal authorities appeared to accept Adebolajo’s case that he was more than a common murderer, an armed rebel with a cause.

Partly, no doubt, this farce reflects the influence of the politics of fear today, the climate of uncertainty and insecurity that leads the authorities in the UK and elsewhere to blow up any localised problem into a threat to ‘our way of life’. Hence the Lib-Con coalition government reacted to the brutal murder of one soldier in Woolwich by holding emergency meetings of its top-level Cobra security committee, as if the country really were at war. The judge and prosecutors reinforced that air of top-level paranoia by treating Private Rigby’s killers as mortal enemies of the state.

These events also illustrate the British authorities’ increasing preoccupation in recent years with punishing thought crimes. UK legislation now makes clear that people can be prosecuted and punished, not only for what they do, but for what they think or say. Thus, for example, penalties for offences of violence can be increased if the court decides that the offence was ‘aggravated’ by racial or religious hatred. In effect, offenders can be punished twice – once for the crime they committed, and again for what was going on in their heads at the time.

The Woolwich sentences introduce us to what many laymen might consider the strange concept of politically ‘aggravated’ murder. The rules outline the types of cases in which a whole-life tariff might be appropriate. These include not only murder involving a substantial degree of premeditation, child murder and murder involving sexual sadism, but also ‘murder done for the purpose of advancing a political, religious or ideological cause’. So Mr Justice Sweeney spelt out in his sentencing remarks that he was imposing the whole-life tariff on Adebolajo, not because of the brutality or the premeditation involved, but primarily because ‘I’m sure this was a murder done for the purpose of advancing a political, religious or racial cause’. In other words, the fact that the pair had, as the judge said, ‘butchered’ Lee Rigby was apparently overshadowed by the extremist thoughts they were having as they hacked him to death and the extremist things Adebolajo said to bystanders videoing the aftermath the murder. This emphasis on the killers’ supposed ‘political, religious or racial’ thought crime effectively elevates their sordid act into a principled stand.

There is a striking historical contrast here with the British state’s attitude to the IRA during the Irish War, a conflict which echoed in the headlines this week when a republican suspected of the 1982 Hyde Park bombing, which killed four soldiers, walked free from court. Back then, the British authorities knew they were engaged in a war over national sovereignty against a politically motivated and well-supported Irish republican movement. In order to downplay the political and military threat to their power this conflict posed, the authorities sought to depict the IRA as a small gang of common criminals, as when denying prisoner-of-war status to the 10 Irish republican hunger strikers who died the year before the Hyde Park bombing. Today, by contrast, the British and Western authorities are faced with very sporadic attacks from a handful of nihilistic Islamist zealots. Yet rather than treat these fringe fanatics as the marginalised criminals and murderers they are, the panic-stricken authorities appear determined to depict them as a political force to be feared.

Of course, at the same time as emphasising that the killing of Private Rigby advanced an ‘extreme’ Islamist cause, the judge was keen to emphasise that he was not suggesting Muslims were in any way responsible. Instead, Mr Justice Sweeney told the murderers, apparently with all the authority of an Islamic scholar, that their beliefs and actions were ‘a betrayal of Islam’. It was this which led to the shouting and scuffle in the dock that ended with the killers being dragged off to the cells. Few of us will have felt any sympathy for the brutal murderers of Private Lee Rigby. However, I admit to thinking the crazed Adebolajo had a point when he yelled at Mr Justice Sweeney from the dock: ‘You know nothing about Islam!’ British judges and politicians seem not to know much about how to deal with homicidal maniacs these days, either.

Outside the Old Bailey on Wednesday, a few British nationalists hoisted a mock gallows and demanded the death penalty. Meanwhile inside, Michael Adebowale’s lawyer said that his martyrdom-seeking client pretty much agreed with them: ‘He intended to die and remains of the view that he should be put to death.’ The Woolwich killers might not have got the glorious deaths as ‘soldiers of Allah’ that they were seeking. But by politicising the verdicts, the UK authorities have done their dirty work for them, and turned two contemptible murderers into martyrs.

Mick Hume is spiked’s editor-at-large. His book, There is No Such Thing as a Free Press… And We Need One More Than Ever, is published by Societas. (Order this book from Amazon(UK).) Visit his website here.

You’ve read 3 free articles this month.

Support spiked and get unlimited access.

Help us hit our 1% target

spiked is funded by readers like you. It’s your generosity that keeps us fearless and independent.

Only 0.1% of our regular readers currently support spiked. If just 1% gave, we could grow our team – and step up the fight for free speech and democracy right when it matters most.

Join today from £5/month (£50/year) and get unlimited, ad-free access, bonus content, exclusive events and more – all while helping to keep spiked saying the unsayable.

Monthly support makes the biggest difference. Thank you.

Comments

Want to join the conversation?

Only spiked supporters and patrons, who donate regularly to us, can comment on our articles.