Why the Russian Revolution matters

A new film busts the myths surrounding 1917.

Want unlimited, ad-free access? Become a spiked supporter.

1917: Why the Russian Revolution Matters is an inspiring and important film made by the education charity WORLDwrite. Like some of its earlier productions – such as Everything is Possible, about the radical Suffragette Sylvia Pankhurst, and Every Cook Can Govern, about the Trinidadian Marxist CLR James – this film is not only crowdfunded, but also crowdfilmed, by a crew of young volunteers. And like those other films, it offers both informed historical analysis and a refreshingly positive and hopeful view of humanity’s potential to create a different, better society. What this new documentary also does, though, is to articulate an understanding of the Russian Revolution that is in danger of becoming obscured and forgotten.

spiked has already carried a piece by one of the film’s producers, Fraser Myers, explaining how it seeks to challenge a number of persistent myths about 1917. I have to say I was surprised by the vitriol oozing through many of the comments on his article (perhaps there will be a similar slick of odium below this one). Haters gonna hate, I suppose, but it does seem a little odd that this 100-year anniversary still apparently provokes such strong feelings that some people cannot bear to hear their understandings of history challenged.

The reason is perhaps less to do with the past and everything to do with the present. Indeed, the film defies the temper of our times in putting forward an optimistic view of people’s capacity to change the world. As the director, Ceri Dingle, puts it, ‘Our film challenges a misanthropic view of history that sees every attempt to change society for the better as a disaster-in-waiting’. The various contributors interviewed for the documentary (including some regular spiked contributors like Mick Hume, Frank Furedi and James Heartfield), emphasise how the revolution was a transformative moment in world history because it made real and tangible the aspiration of millions to take control of their lives.

It may be surprising, then, to learn that the film actually opens by declaring the failure of the revolution. Of the many myths that still surrounds 1917, possibly the main one is that, for good or ill, the Bolsheviks succeeded in what they set out to do. Its many detractors argue that the repressive and brutal regime that ruled the USSR until its collapse in 1991 was the direct and inevitable product of the revolution. Which is why they argue it was a terrible idea from the outset. Meanwhile, its few defenders maintain that, despite the gulags and the deprivation, ‘actually-existing socialism’ wasn’t all that bad and even had some quite positive aspects.

Thankfully, this film offers a different and more thoughtful perspective, rejecting what Furedi calls the ‘Disneyfication’ of history, whereby the past is treated either as a safe and commodified spectacle or as a trite morality tale that affirms the prejudices and preoccupations of the present. 1917: Why the Russian Revolution Matters avoids such simplifications by insisting on the importance of setting the events of the revolutionary era in their context, as a sometimes difficult and uncomfortable history that demands a serious reckoning.

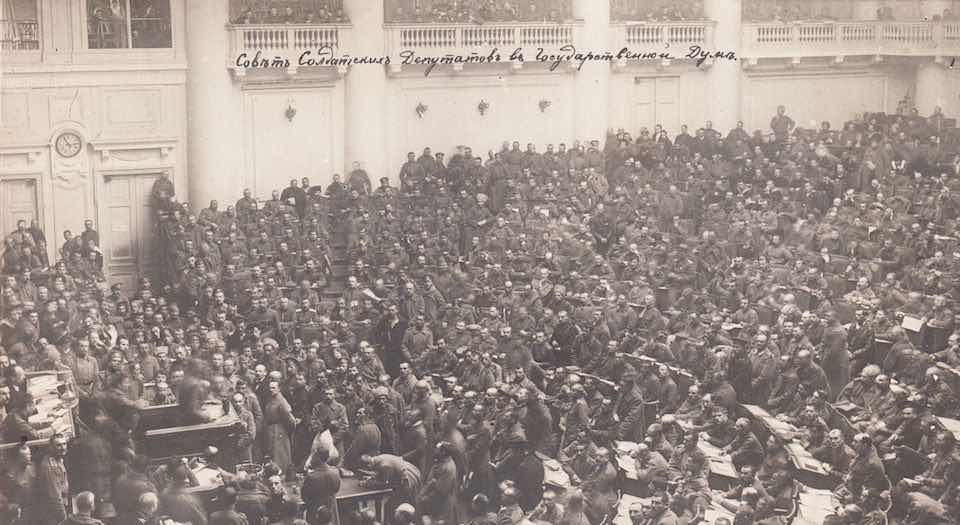

In some detail, the film takes us through the events of the 1905 and February 1917 revolutions, discussing the context of world war and the particularities of Russia’s society at the time. It then examines the role of individuals in history, considering Lenin’s return from exile in April 1917 and his decisive role in leading the October revolution. It goes on to discuss the terrible violence and terror that followed, not as part of the act of revolution itself (which was near bloodless), but as the product of civil war as the ‘Whites’ fought to restore the old order. Following this is an exploration of the role played by Western powers who aimed, in Winston Churchill’s words, to ‘strangle Bolshevism in its cradle’. The newly formed Red Army successfully fought off these threats, but at an awful cost, as the post-revolutionary conflict wiped out swathes of the Bolshevik membership.

One of the film’s interviewees, Phil Cunliffe (author of Lenin Lives, a hugely entertaining counter-factual history of the revolution), makes the point that the fate of the new society being built in Russia ultimately depended on developments elsewhere. The objective, as far as its key leaders were concerned, was never to construct ‘socialism in one (isolated and underdeveloped) country’, but to provide the spark that could ignite an international explosion of revolutionary change. It did indeed inspire a global movement, but the tragic defeat of revolution elsewhere, particularly in Germany, ensured its ultimate failure in Russia, too.

So, why does 1917 still matter? To be sure, from today’s vantage point, this past can feel not just like a foreign country but another planet. The film works in various ways to bring the events of 1917 closer, for example by intercutting archive footage with film of the same locations in contemporary St Petersburg. Many of the interviewees talk about the revolution’s importance for their own personal political histories, and offer striking and vivid accounts of particular moments – Heartfield, especially, has a historian’s eye for the telling detail that brings the story to life.

In the end, though, our motive for trying to understand the past must be about our present and our desire to stake a claim on the future. That is exactly the aspiration that animates this film, and is why I heartily recommend it.

Philip Hammond is professor of media and communications at London South Bank University.

WORLDwrite’s 1917: Why The Russian Revolution Matters will premiere at the Battle of Ideas festival in London on Saturday 28 October. Find out more here.

Watch the trailer:

You’ve read 3 free articles this month.

Support spiked and get unlimited access.

Help us hit our 1% target

spiked is funded by readers like you. It’s your generosity that keeps us fearless and independent.

Only 0.1% of our regular readers currently support spiked. If just 1% gave, we could grow our team – and step up the fight for free speech and democracy right when it matters most.

Join today from £5/month (£50/year) and get unlimited, ad-free access, bonus content, exclusive events and more – all while helping to keep spiked saying the unsayable.

Monthly support makes the biggest difference. Thank you.

Comments

Want to join the conversation?

Only spiked supporters and patrons, who donate regularly to us, can comment on our articles.