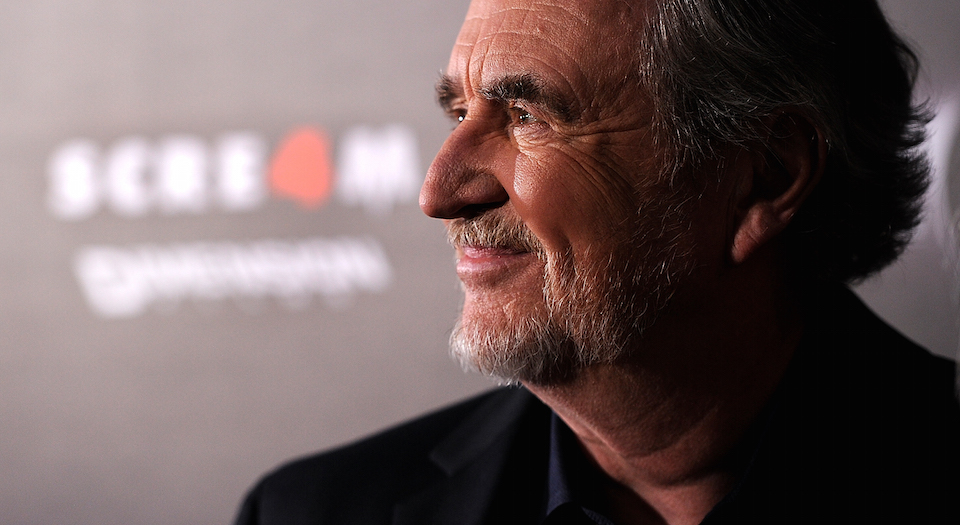

Wes Craven: exploring the horror within

The Nightmare on Elm Street director confronted the human condition in an age of unreason.

Wes Craven has died at the age of 76. I found myself more affected than I would have expected. But, then again, not only did I appreciate his artistic talent, and his tweets about his cats; Craven was also a part of my growing up.

I was 14 when I watched my first horror movie – Craven’s A Nightmare on Elm Street (1984). It was the early Nineties. My friend Jo acquired the video from her older brother, and we would sit in her parents’ frontroom (my parents would never have allowed such a thing) and watch Johnny Depp being sucked into his mattress, only to be regurgitated as a fountain of blood. Watching it felt transgressive and scary. It was also exciting. So exciting, in fact, that we would repeat this experience after school almost every day for weeks. We would constantly quote the movie, playing out the boiler-room scene in which the main character Nancy confronts the nightmare born of her parents’ cruelty.

Watching teenagers being slashed by Freddy Krueger, the man monster whom Slavoj Zizek describes as ‘the obscene and revengeful figure of the “father of enjoyment”, [a] figure split between cruel revenge and crazy laughter’, was a rite of passage for me and my friends (1). Craven introduced the concept of violence into my life in a way that felt real and frightening, yet at the same time safe and unreal. And when Scream came out in 1996, where the kids who know the rules, as we did, get slashed anyway, Craven had again shifted the goalposts for scary.

Craven’s work is often reduced to three archetypal films that helped define the horror genre in the Seventies, Eighties and Nineties: The Last House on the Left (1972), which touched on the human condition and established the horror film as an artistic experience; A Nightmare on Elm Street, which showed the subconscious as the place where nightmares can become reality; and Scream, in which cynical postmodernism falls victim to the reality it has created. But what is too often neglected in the horror discussion is how Craven was fundamentally always interested in humans exposed to a world of unreason. He was able to define, and redefine, this condition through his movies.

He claimed to have been unfamiliar with horror films until a friend dragged him to see Night of the Living Dead. He was enthralled by the energy it unleashed in its audience, and its dramatic potential for political commentary (2). In his debut film The Last House on the Left (a reworking of Ingmar Bergman’s The Virgin Spring (1960)), the rape and murder of two teenage girls, and the subsequent revenge taken by their family, is shown in gory detail. Motives are not explored. Instead, the horror derives, in the main, from the failure to explain, and the sheer exposure to human violence in its uncivilised form. The film was famously lauded at the time by critic Robin Wood as an artistic exploration of the inherent violence of ‘the American situation’, at a time when the Vietnam War was a constant presence for ordinary Americans (3). Craven’s film showed how this violence did not come from without, but from within.

Craven confronted people with their own potential for nihilism and cruelty. In Scream, made almost 25 years after The Last House on the Left, he cannily frames the human potential for violence in the postmodern era. The teens become their own slasher killer, the human monster is pure simulacrum, a copy without original – but no less deadly.

The loss of Wes Craven means we will never know how he would approach today’s horrors. How would he have shown to us our current post-political condition? What shape would have been the monster of today’s nightmares? These are questions to which Craven would no doubt have provided thrilling answers.

Maren Thom is a writer based in London.

Picture by: Getty Images / Frazer Harrison

To enquire about republishing spiked’s content, a right to reply or to request a correction, please contact the managing editor, Viv Regan.

Comments

Want to join the conversation?

Only spiked supporters and patrons, who donate regularly to us, can comment on our articles.