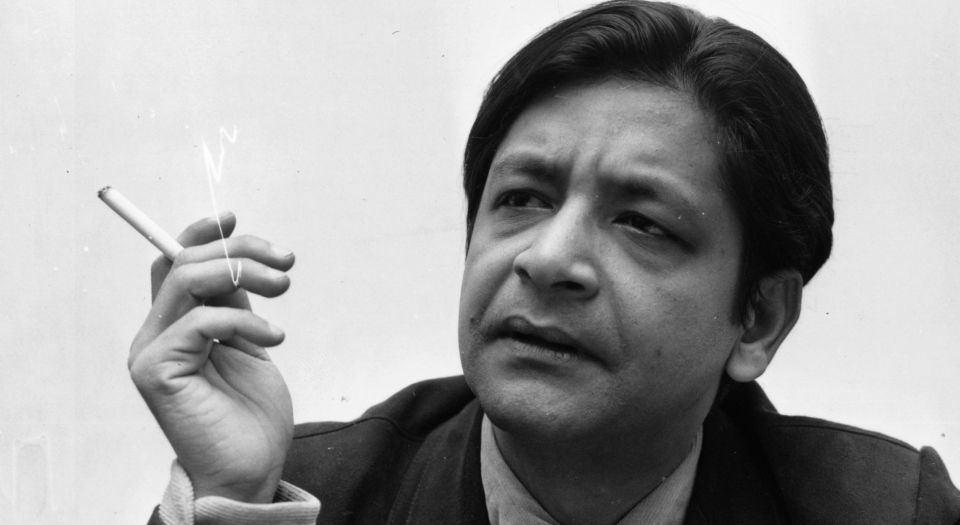

VS Naipaul: his own person

The great writer rejected victimhood and lazy thinking.

Want to read spiked ad-free? Become a spiked supporter.

The sad news of writer VS Naipaul’s death, on 11 August, came to me while I was on holiday in my birthland of Mauritius and the neighbouring French department island, Réunion. It was a striking coincidence: I first came across Naipaul when, as a young man, I read a long 1972 essay he wrote about Mauritius, bearing the unflattering title The Overcrowded Barracoon. It was an unkind, critical essay, albeit about a Mauritius that was a very different kind of nation then, just four years after it became independent from the British Empire.

In the essay, he follows the country’s first election, interviewing and mocking politicians who hollowly appropriated symbols of the US black-power movement – afro hair, black leather – yet supported trade with Apartheid South Africa. It is an example of Naipaul at his best – questioning, investigative, judgemental, but also compassionate towards the islanders, many of whom felt they were living in a prison-house at the time: ‘To the travel writers, who have set to work on Mauritius, the island is a “lost paradise” which is “being developed into an idyllic spot”. It is an island which the visitor leaves with a “feeling of peace”. To the Mauritian who cannot leave it is a prison: sugarcane and sugarcane, ending in the sea.’

Naipaul often wrote about ‘half-made’ societies, and the desire of people to escape them. Of Indian ancestry, he was born on the small Caribbean island of Trinidad, in 1932, which was also a sugar island colony of the British. Naipaul was a clever young man. His father was a local journalist. He studied hard and secured a scholarship to study English at Oxford University in 1950. He became lonely and homesick, and had a mental breakdown. But new friends pulled him through.

He moved from Oxford to London in 1954, with hardly any money. He got a job at the BBC as a freelance journalist. Using a BBC typewriter, he began writing his first collection of fiction. His first short novel, The Mystic Masseur, was published in 1957. Half a century later, Naipaul had collected a string of literary awards. He won the Booker Prize in 1971 and the Nobel Prize for Literature in 2001. He wrote 13 major works of fiction and much more non-fiction about his extensive travels across the world.

Naipaul never returned to Trinidad; he made England his home. But he was no romantic. He did not see England through rose-tinted glasses, and he resisted being pinned to a particular identity. In an interview with The Times of India in 2002, he was asked if the support from Indians for his Nobel win – he was the second Indian to receive the prize – made him feel ‘more Indian’. Naipaul retorted, ‘What do you mean more Indian? I don’t like such terms… I was born in Trinidad, I have lived most of my life in England and India is the land of my ancestors, that says it all. I am not English, not Indian, not Trinidadian, I am my own person.’

He detested race and identity politics. In 1974 he wrote: ‘It’s very attractive to people to be a victim. Instead of having to think out the whole situation, about history and your group and what you are doing… if you begin from the point of view of being a victim, you’ve got it half-made. I mean intellectually.’ This is what makes Naipaul so important and unique in ‘diasporic’ literature and English literature. He is the classic, alienated outsider.

The first novel I read by Naipaul was his 1961 classic, A House for Mr Biswas. It is both funny and tragic, a novel about an angry young man trapped in an environment of Hindu superstition, the toil of hard labour and family convention. Mr Biswas has no control over his life. From birth to death he lives in squalid houses that do not belong to him. There is no room to call his own. The only freedom he finds is through his autodidactic quest for knowledge, which he finds through European culture – the writings of Charles Dickens and Marcus Aurelius.

Naipaul was attacked by many for being neocolonialist and an Islamophobe. But this misunderstands him. What makes him a truly great writer is his ability to inhabit the complex imaginative and intellectual landscape of both colonised and coloniser. And his main criticism of Islam was that it produced, to his mind, the worst of colonial invaders, an issue most postcolonial theorists choose to ignore. His travels across non-Arab Muslim countries led him ‘to discover that no colonisation had been so thorough as the colonisation that had come with the Arab faith… The faith abolished the past. And when the past was abolished like this, more than an idea of history suffered. Human behaviour, and ideals of good behaviour, could suffer.’

Naipaul died peacefully, six days before his 86th birthday. He leaves behind a great body of works of masterful and uncomfortable fiction, essays, travel writings and musings on the turbulent and difficult world we live in. Throughout it all, he was his own person.

Manick Govinda is programme director for SPACE and a freelance arts consultant. He writes here in a personal capacity.

Picture by: Getty

Who funds spiked? You do

We are funded by you. And in this era of cancel culture and advertiser boycotts, we rely on your donations more than ever. Seventy per cent of our revenue comes from our readers’ donations – the vast majority giving just £5 per month. If you make a regular donation – of £5 a month or £50 a year – you can become a and enjoy:

–Ad-free reading

–Exclusive events

–Access to our comments section

It’s the best way to keep spiked going – and growing. Thank you!

Comments

Want to join the conversation?

Only spiked supporters and patrons, who donate regularly to us, can comment on our articles.