There’s more to university than getting a good job

Students suing their alma maters speaks to the devaluation of learning.

Want unlimited, ad-free access? Become a spiked supporter.

Life brings many joys and disappointments. For as many good things that happen, there will be missed opportunities, rejections, failures. Most of us take these on the chin, and, as Samuel Beckett advised, try to fail better next time.

But it seems not everyone is so thick-skinned. Take Faiz Siddiqui, the Oxford graduate suing his alma mater for not giving him a first-class degree – 16 years ago. Siddiqui is seeking £1million in lost earnings on the basis that his failure to get a first stopped him from becoming a ‘high-flying commercial barrister’.

This is absurd. By the same logic I could sue my primary school, St Joan of Arc, for removing the monkey bars when I was in Year Three, thus thwarting my potential as a gymnast. I could take my GCSE teacher to court for telling me I couldn’t sew straight and in the process killing my dreams of being a designer.

Siddiqui seems incapable of accepting that it was most likely his own failings as a student, or perhaps his choices as an adult, that prevented him from getting his dream job. Oxford has admitted there was a shortage of staff for some of the time Siddiqui was there, affecting his studies. But even so, the point of being a university student, as opposed to a high-school one, is that you take responsibility for your learning; you set out to discover as much as being lectured and taught. A little self-awareness would serve Siddiqui better than a court case against Oxford.

But Siddiqui’s behaviour isn’t surprising. There have been other instances of students suing their universities. And this is the logical outcome of the commercialisation of education. When university is presented as little more than a stepping stone to a career and the thing that keeps the British economy going – that is, in narrow economic terms – it is hardly surprising that, like customers, students ask for money back when they don’t get the product they wanted.

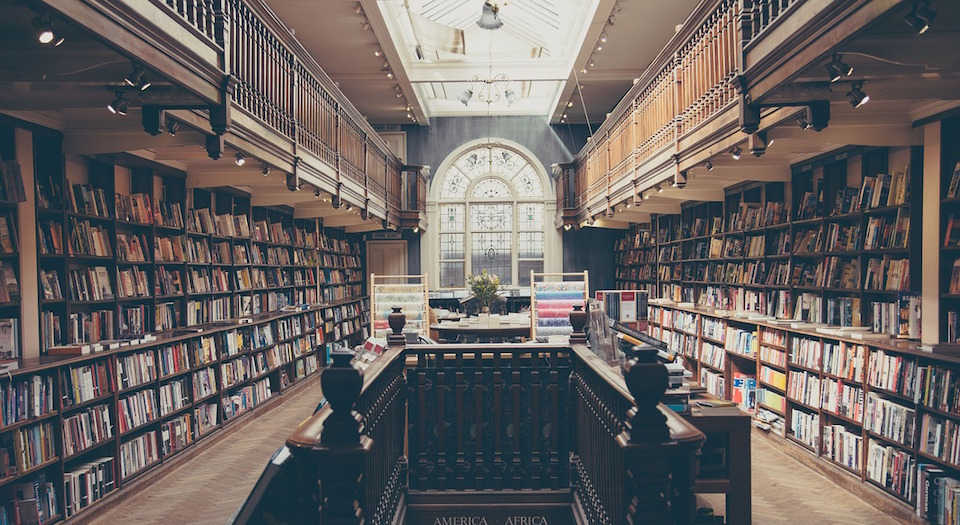

Increasingly, students are encouraged to see education as something to put on their CVs. A first-class degree is treasured primarily as a guarantee for a good job. Endless newspaper articles by unemployed graduates, temper tantrums as journalism, tell us how outrageous it is that one cannot waltz out of Durham into a full-time top job. The underlying question is always: what was university for? But surely it is for more than getting a job? It’s rare and refreshing to find a student spending long hours in the library simply because they love learning rather than viewing their degree as a ticket to a corner desk at Goldman Sachs.

Almost every trend in higher education encourages students to see their time at university as a transaction. Students are treated like consumers. Students’ unions spend their time trying to make university life as satisfactory, safe and comfortable as possible, as if it were a flight rather than an education. Universities survey students on how satisfied they are with their teaching, and hire and fire lecturers on the basis of the feedback. Both adding to and springing from this commercialisation is the matter of student fees. The average student debt for an English graduate, for example, is £44,000, the highest in the English-speaking world. All the focus on career prospects, value for money and ‘student experience’ means that the real value of university – the pursuit of knowledge – becomes an afterthought. And the student becomes more like a shopper than a free-thinking individual seeking to expand his or her mind.

We should encourage people to go to university, not as the default step between school and working life, but as a way of broadening their minds, challenging their preconceived opinions, and learning new things about a subject they’re passionate about. Yes, if you do well, it might give you an advantage in certain areas of employment, but this shouldn’t be the reason for university; making it the reason is robbing university life of its purpose.

The more we devalue education, and reduce it to an instrument of economic betterment, the less surprising cases like Siddiqui’s will become. The more we treat students like overgrown children, who need to be mollycoddled, praised and made to feel safe all the time, the more likely it is they won’t be able to act like adults and take responsibility for their own learning and lives. A good education comes from good teaching; a great education only comes to students who really want to learn.

Ella Whelan is assistant editor at spiked. Follow her on Twitter: @Ella_M_Whelan

You’ve hit your monthly free article limit.

Support spiked and get unlimited access.

Support spiked and get unlimited access

spiked is funded by readers like you. Only 0.1% of regular readers currently support us. If just 1% did, we could grow our team and step up the fight for free speech and democracy.

Become a spiked supporter and enjoy unlimited, ad-free access, bonus content and exclusive events – while helping to keep independent journalism alive.

Monthly support makes the biggest difference. Thank you.

Comments

Want to join the conversation?

Only spiked supporters and patrons, who donate regularly to us, can comment on our articles.