The disease of ‘public health’

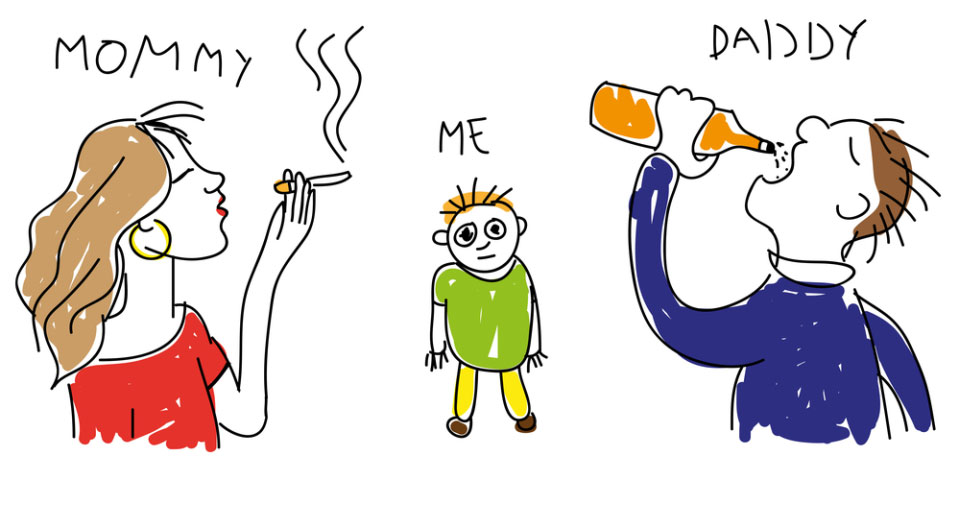

We are in the midst of an epidemic of lifestyle moralism.

In the second of spiked’s series of essays on paternalism, Chris Snowdon looks at the increasingly illiberal nature of public health policy and initiatives.

An abridged list of policies that have been proposed in the name of ‘public health’ in recent months includes: minimum pricing for alcohol, plain packaging for tobacco, a 20 per cent tax on fizzy drinks, a fat tax, a sugar tax, a fine for not being a member of a gym, graphic warnings on bottles of alcohol, a tax on some foods, subsidies on other foods, a ban on the sale of hot food to children before 5pm, a ban on anyone born after the year 2000 ever buying tobacco, a ban on multi-bag packs of crisps, a ban on packed lunches, a complete ban on alcohol advertising, a ban on electronic cigarettes, a ban on menthol cigarettes, a ban on large servings of fizzy drinks, a ban on parents taking their kids to school by car, and a ban on advertising any product whatsoever to children.

Doubtless many of the proponents of these policies identify themselves as ‘liberals’. We must hope they never lurch towards authoritarianism. We have come a long way from the days of doctors issuing friendly advice. Consider this comment from the president of the Royal College of Physicians in the mid-1950s when the link between smoking and lung cancer was becoming clear: ‘If we go beyond facts, to the question of the giving of advice to the public as to what action they should take in the light of the facts, I doubt very much whether that should be a function of the College.’ (1)

Today, the same Royal College of Physicians releases its own ‘manifesto’ every few years and wants it to be a crime for people to smoke in their own car, even if there are no passengers.

Mission creep

Health once meant the absence of disease. Since the 1970s, however, the World Health Organisation has defined health as ‘a state of complete physical, mental and social well-being’ and demands ‘Health for All’. As Petr Skrabanek noted in 1994, this gives them a mission that can run forever: ‘Anyone sick or, God forbid, on their deathbed, anyone not experiencing the euphoria of positive health, as defined by WHO, would spoil this objective. Old people drifting into the oblivion of dementia, sour spinsters, jilted lovers, ruined gamblers, wives of drowned fishermen, victims of violence, or immured lunatics would also spoil the picture. Even Christians, in their boundless optimism, have been more realistic in deferring the promise of complete happiness to the afterlife.’ (2)

As the definition of ‘health’ has been changed, so too has the meaning of ‘public health’. It once meant vaccinations, sanitation and education. It was ‘public’ only in the sense that it protected people from contagious diseases carried by others. Today, it means protecting people from themselves. The word ‘epidemic’ has also been divorced from its meaning – an outbreak of infectious disease – and is instead used to describe endemic behaviour such as drinking, or non-contagious diseases such as cancer, or physical conditions such as obesity which are neither diseases nor activities. This switch from literal meanings to poetic metaphors helps to maintain the conceit that governments have the same rights and responsibility to police the habits of its citizens as they do to ensure that drinking water is uncontaminated. It masks the hard reality that ‘public health’ is increasingly concerned with regulating private behaviour or private property.

The anti-smoking campaign is where the severe new public-health crusade began, but it is not where it ends. Libertarians warned that the campaign against tobacco would morph into an anti-booze and anti-fat campaign of similar intensity. They were derided; ridiculed for making fallacious ‘slippery slope’ arguments. In retrospect, their greatest failing was not that they were too hysterical in their warnings but that they lacked the imagination to foresee policies as absurd as plain packaging or bans on large servings of lemonade, even as satire.

The slippery slope was both predictable and predicted. The only surprise is how little time it took for the British public to taken in, when only a few years earlier they would have scoffed at the idea of drinkers and salad-dodgers being next in line. Once again, all it took was a change in terminology. A ‘binge-drinker’ had traditionally been someone who went on a session lasting several days. Now it means anyone who consumes more than three drinks in an evening. Similarly, the crude and arbitrary nineteenth century measure of body mass index (BMI) has been used to categorise the chubby as ‘obese’ and the fat as ‘morbidly obese’. Sugar is ‘addictive’ now – and ‘toxic’. ‘Big Food’ is the new ‘Big Tobacco’. The anti-smoking blueprint of advertising bans, tax rises and ‘denormalisation’ provides the roadmap for action. At this stage, there is nothing to be gained from saying we told you this would happen, but we told you this would happen.

Today, if you are gripped by an urge to eradicate some bad habit or other, you no longer have to make a nuisance of yourself knocking door-to-door or waving a placard in some dismal town square. You can instead find yourself a job in the vast network of publicly funded health groups and transform yourself from crank to ‘advocate’.

No wonder, then, that everything – from gambling and climate change to gay-rights and international finance – is now pitched as a ‘public health issue’. No wonder, also, that a swarm of political activists and belligerent academics have transformed themselves into ‘public health professionals’ as a way to win power without winning votes. Although ‘public health’ is still popularly viewed as a wing of the medical profession, its enormous funding and prestige has attracted countless individuals whose lack of medical qualifications is compensated by their thirst for social change. The movement is dominated by sociologists, engineers, psychologists, lawyers, epidemiologists and other academics whose contempt for consumer capitalism is often more conspicuous than their concern for people’s health and wellbeing. Whether it is attacking multinational corporations or campaigning against ‘health inequalities’ (which are invariably a proxy for income inequalities), the endlessly accommodating field of ‘public health’ is a magnet for unelectable social scientists and moral entrepreneurs.

Longevity

The self-styled champions of the oxymoronic ‘public health’ enterprise are fond of drawing comparisons between the relatively small number of deaths from drug overdoses and road accidents with the much larger death toll from cardiovascular disease and cancer. References to downed jumbo jets and 9/11 fatalities hold a particularly ghoulish fascination for them. Numerical equivalence does not translate to moral equivalence, however. In our ageing population, with 93 per cent of the population living beyond the age of 60 and two-thirds living to at least 75, the issue is not so much ‘preventing’ diseases as ‘swapping’ one chronic disease of old age for another. Someone who dies of cancer at the age of 84 is not the victim of a preventable tragedy in the same way as a 20-year-old victim of terrorism and it is disingenuous to pretend otherwise. Likewise, someone who avoids dying of lung cancer at the age of 84 but then succumbs to prostate cancer at age 85 did not have his life ‘saved’ in any meaningful way.

In short, the public health lobby has lost – or cheerfully abandoned – the concept of premature death. This is not a health movement, but a longevity movement. It is true that almost every death is theoretically preventable, but only in the world of ‘public health’ is it seen necessary to move every mountain to prolong the lives of geriatrics. The concept of a “good innings” or “dying of old age” are anathema to them. When all the preventable causes of deaths have been controlled, we will be free to die from the only cause of mortality that their policies actively encourage: boredom.

Morality

It is not necessarily wrong to view longevity as the ultimate goal in life, but it is only an opinion. As with all opinions, there are those who beg to differ (and those who beg to differ do not demand that others be compelled to live a bacchanalian existence). The question is why the opinion of the longevitists has become the dominant view not only in medicine but in politics, too. Matters that are routinely described as ‘public health issues’ – most notably, drinking, smoking and eating – are matters of private, not public, behaviour. Aside from instances of excessive alcohol consumption leading to public disorder, these personal habits should barely feature on the radar of a liberal democracy.

It is sometimes said that ‘unhealthy lifestyles’, especially smoking, place an intolerable burden on the NHS, but the data show that it is those who live longest who are the greatest ‘burden’ on the public purse (3). The uncomfortable truth is that ‘preventable deaths’ save the taxpayer a fortune in pensions, healthcare, prescriptions and nursing-home provision. This has been confirmed by so many studies that public-health campaigners can scarcely be unaware of it and yet they continue to appeal to financial prudence because it has a superficial plausibility and because it is all that stands between them and being told to mind their own business. On the rare occasions when they are challenged on the facts, the scoundrels sheepishly abandon their claims and accuse their opponents of boiling everything down to pounds, shillings and pence. Physician, heal thyself.

Persistent belief in the ‘cost to the taxpayer’ argument is surely not enough to explain why the ideology of ‘health at all costs’ has become an unchallengeable doctrine amongst the political class without ever having to submit itself to public debate, let alone stand for election. A number of explanations can be offered. Perhaps an ageing population is more prone to thoughts of morbidity and hypochondria. Perhaps the crumbling Ponzi scheme of the welfare state requires scapegoats to blame for its spiralling costs. Perhaps these scapegoats also offer an easy explanation for why Britain’s life expectancy is not commensurate with the peculiar fantasy that the NHS is the ‘envy of the world’. Perhaps ideologically bereft politicians are susceptible to fantasies of ‘saving lives’ and improving the ‘health of the nation’.

Or perhaps there are more deeply rooted beliefs at work. It is not a novel observation to note that health has taken the place of religion in modern society. It can scarcely be coincidence that the main targets of the public-health movement are the same vices of sloth, gluttony, smoking and drinking that have preoccupied moralists, evangelists and puritans since time immemorial. HL Mencken long ago described public health as ‘the corruption of medicine by morality’. The urge to view death and disease as a punishment for sin has existed for millennia. It manifests itself today in the quest to identify ‘lifestyle factors’ to explain inexplicable diseases and the implicit reassurance given to those who tread the path of purity that the reaper can be kept at bay – a belief that is only occasionally punctured by bewilderment when a ‘healthy’ person keels over and dies.

Risk

In its more candid moments, ‘public health’ describes itself as was it is – ‘lifestyle regulation’. It is not deemed necessary to ask us if we want our lifestyles to be regulated, it is only necessary for numbers on a laptop to show that x number of lives will be ‘saved’ by some intervention or other and that, therefore, politicians can ‘save lives’ by intervening. Leaving aside the fact their own epidemiology suggests that the healthiest options are to exceed their risible alcohol guidelines and to be at least slightly overweight, the mandarins of public health never explain why it is more desirable to live a life of pious self-denial to the age of 85 than a life of gluttonous levity to the age of 75, let alone why dying in extreme old age is so desirable that the force of law must be applied to ensure it.

Asking such questions would require grappling with the trade-off between risk and enjoyment – a balance that all of humanity strikes on a daily basis, but which is absent from public-health discourse. Unlike the rest of us, moral crusaders do not deal in costs and benefits, only in ‘solutions’.

Take the issue of alcohol and breast cancer, for example. Last year, an epidemiological study reported that light drinking increases the risk of the disease by five per cent and that light drinking therefore kills 5,000 women a year. The authors stopped short of counting how many crashed jumbo jets this equated to, but nevertheless claimed that the finding was of ‘great public health relevance’ (5). Perhaps so, but it is of zero private-health relevance. A five per cent increase in a woman’s relative risk of contracting breast cancer has so little effect on her absolute risk of contracting breast cancer that few rational women would deprive themselves of a source of enjoyment on the basis of it.

Trivial risks such as this can only be viewed as being of ‘great public health relevance’ by multiplying them by the population of a whole country or – as the researchers did in this instance – by the population of the entire world. But this is sleight of hand. Issues which are of minimal concern to individuals cannot magically become pressing concerns for society by multiplication. If we extend this logic, we would appreciate that the benefits bestowed on the individual from an activity – which must outweigh the risks, or else the individual would not engage in it – could also be multiplied by millions of people to create an enormous national ‘public benefit’. This, however, would require the moral statisticians to admit that there are upsides to living an ‘unhealthy’ lifestyle. This, in turn, would require an admission that pleasure and enjoyment have value. This they can never do, for their model would fall apart.

The general public puts little faith in epidemiological trash. They know that chocolate will be said to cause cancer today and will be said to cure cancer tomorrow. Lifestyle epidemiology is a branch of the entertainment industry, much relied on by newspaper editors to fill space, but with little lasting influence over lifestyles. On the basis of such evidence, however, the champions of public health tell us that there is ‘no safe level’ of alcohol consumption – a message that echoes the risible mantra that there is no safe level of secondhand smoke – and the neo-temperance lobby calls for ‘tougher regulation by government’. Public-health activists play down the more substantial body of evidence that shows that alcohol consumption reduces the risk of heart disease (a much more common cause of death than breast cancer). It is hard to imagine the public-health lobby telling women to have children early and often, although this would lower their breast cancer risk more than abstaining from drink, and it is inconceivable that the government would legislate to encourage such leporine breeding. As so often in public health, if it doesn’t involve drinking, smoking or eating, it isn’t worth mentioning.

Even by the debased standards of ultra-low-risk epidemiology, a five per cent increased risk is small and most women would view it as a price worth paying for a little light drinking. But if a five-per-cent increase in risk is a price worth paying, what are we to make of more substantial risks? Is a greater risk of diabetes a price worth paying for enjoying an excess of high-calorie food? Is a greater risk of liver disease a price worth paying for years of beer-guzzling? Is a greater mortality risk a price worth paying for a lifetime’s smoking? Who is to draw the line? The mandarins of ‘public health’ would draw it as near to zero as is politically feasible, but in an enlightened society the judgement can only be made by the one person who bears all the risk and enjoys all the benefits: the individual.

Normality

There is something unhealthy about this fixation with longevity. Its flip side is a morbid obsession with images of death and disease that recalls the grinning skeletons of medieval death culture. It began with self-consciously shocking television adverts before moving on to tobacco packaging – and, if the British Medical Association gets its way, onto alcohol packaging, too. At least the peasants of the Middle Ages were victims of genuine epidemics who knew that the icy hand of death could be right around the corner. The paradox of the modern public-health movement is that it has reached its peak of power at a time when life is long.

‘Denormalisation’ is the name of the game. It began, inevitably, with smoking/smokers, but denormalising drinking and drinkers is now on the political agenda. Considering the profound impact such policies have in stigmatising the vulnerable, robbing the poor and trampling on ancient liberties, it is time to ask whether the assortment of neurotics and authoritarians that make up the modern ‘public health’ movement is best placed to decide what is normal.

John Stuart Mill’s opinion of the peculiar longevitists bears repeating: ‘It is not, naturally and generally, the happy who are most anxious either for prolongation of the present life or for a life hereafter; it is those who never have been happy. Those who have had their happiness can bear to part with existence, but it is hard to die without ever having lived.’ (4)

What the modern puritans call ‘health policy’ often involves profound questions of economics, law, ethics, constitutional rights and philosophy, of which they are largely, if not entirely, ignorant. These issues are too important to be trampled by monomaniacs who have not learnt the art of living.

Society finds it easy to ridicule the pointy-headed puritans and lemon-sucking prohibitionists of earlier eras, but we are peculiarly shortsighted when it comes to identifying the same scolds amongst us today. Once identified, they should be treated with the same derision and denormalisation that they dish out so freely. Current efforts to portray ‘Big Food’ as the natural successor to ‘Big Tobacco’, for example, would be merely comic if those who made the comparison were not gripped by the delusion that they are the heirs to John Snow and Alexander Fleming, with resources of wealth and influence to match their egos.

Anyone who uses such terms without irony should be treated with a mixture of pity and contempt; dunces who should not be humoured. Those who go beyond childish rhetoric and call for the force of law to be directed at people ‘for their own good’ should be viewed as anti-social menaces and ostracised from civilised gatherings. The ‘sin taxes’ they so often espouse should be seen as what they are: extortion rooted in prejudice; fines for living in a way that displeases a purse-lipped elite.

The issue of risk should also be viewed from the right end of the telescope. In a society in which almost everybody willingly puts themselves at risk, those who attempt to lead lives of ascetic self-denial should be regarded as curious outliers. They have every right to pursue extreme longevity if that is their wish, but they have no right to bully and cajole those of us who prefer the good life into emulating them. Whether they are well-intentioned do-gooders, sly charlatans or malevolent bigots, they must be tolerated in a civilised society, but they do not have to be suffered gladly and they should never be given the reins of power. It is time to denormalise the demagogues of ‘public health’.

Christopher Snowdon is director of lifestyle economics at the Institute of Economic Affairs. He is also the author of The Art of Suppression: Pleasure, Panic and Prohibition since 1800 (2011), The Spirit Level Delusion (2010) and Velvet Glove, Iron Fist: A History of Anti-Smoking (2009).

To enquire about republishing spiked’s content, a right to reply or to request a correction, please contact the managing editor, Viv Regan.

Comments

Want to join the conversation?

Only spiked supporters and patrons, who donate regularly to us, can comment on our articles.