The NSPCC’s war on youth culture

The charity’s new anti-gang initiative sounds suspiciously like an assault on young people.

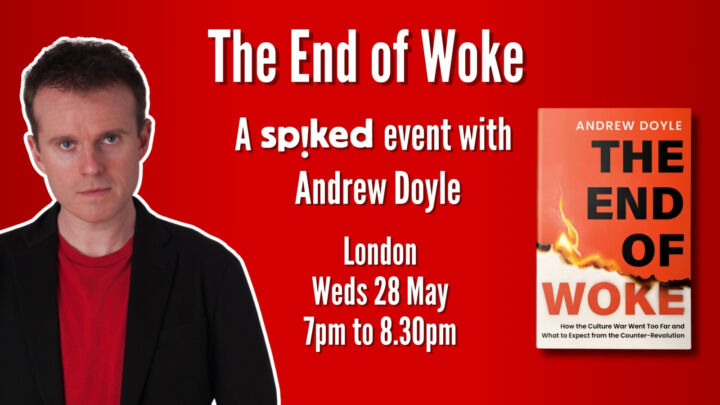

Want to read spiked ad-free? Become a spiked supporter.

Following the widespread riots that plagued English cities in the summer of 2011, the Home Office published a report entitled Ending Gang and Youth Violence. Rather than blaming the riots on the provocations of a hostile police force, Westminster looked to the role that professional criminal outfits had played in encouraging the looting and criminal damage that spread through cities that summer.

Of those arrested in the riots, one in five were identified as gang members – considering the number of people who protested peacefully and consequently didn’t face arrest, the story of a criminally organised uprising seems more than a little threadbare. The Home Office reported that in London – the area with greatest concentration of gangs in the UK – only 22 per cent of violent crime more generally is gang-related. This proportion shrinks dramatically for the rest of the country. What’s more, there are no associated statistics to suggest that children or young people are particularly involved in these activities. In fact, one might safely assume that these actions are largely carried out by organised crime syndicates run by adults.

Why, then, has the NSPCC launched a national helpline to protect children from a gang culture that, though alive in some form, is hardly thriving? This week, the NSPCC, backed by the Home Office, set up a helpline to provide advice for parents concerned about their children’s involvement in gangs. The NSPCC’s statistical justification for the campaign is that one-in-six young people aged between 13 and 15 claims to know a gang member, yet it is startlingly vague about what being a gang member entails. It fails to clarify whether or not the adolescents surveyed are acquainted with members of violent criminal gangs or if some of their friends simply wear matching hoodies and spraypaint rude words on underpasses.

The helpline’s homepage lists supposedly telltale signs of gang association for parents to look out for. These include your child spending time with people you don’t know; coming home with unexplained injuries; getting into trouble at school; becoming secretive; and staying out late. The list does go on to include ‘evidence of violent or criminal activity’ as an indicator, but otherwise it reads rather like a rundown of the general behaviour to expect from any adolescent worthy of the name. It seems that the NSPCC’s latest crusade is not about tackling a criminal underworld that sucks in children; rather, it’s a concerted assault on the habits of young people and the elements of youth culture that pearl-clutching parents find distasteful.

Ever since teenagers have been a recognisable cultural force, young people have been drawn to gangs and sub-cultures. Admittedly, the NSPCC is fairly accurate in its assessment of the reasons for this. Gangs and youth movements provide young people with a rebellious outlet – a sense of identity and excitement that is made more attractive by a tinge of the illicit. Each new generation gives birth to a new youth culture – mods, rockers, punks, skinheads, casuals – and each new culture is immediately decried as criminal and violent. In every case, there exists a kernel of truth in the allegation of gang-style behaviour, but only a few of the young people involved in a particular sub-culture will ever engage in serious criminal activity; most stop at casual substance use, with occasional forays into dealing drugs. Serious violence is rarely as widespread as the attendant media panic would have you believe, and the young men billed as a threat to the nation’s moral fibre become a footnote in British cultural history within 10 years or so.

The NSPCC’s project indulges this timeless hysteria, as shown by the structure and spirit of its policy. A programme that earnestly sought to diffuse gang violence and impact the lives of at-risk children would presumably begin with those children in gangs. If sincere steps were being taken to end youth gang violence then helping community workers engage directly with gang members would doubtless be the first priority. Yet the NSPCC’s big idea is to provide an outlet for concerned parents.

In a statement about the project, John Cameron, NSPCC head of child protection, explained the charity’s decision to tackle gang violence, before adding: ‘Parents, carers and other adults often struggle to know where to turn when faced with a young person who they think might be involved in a gang.’

The NSPCC is quite clearly putting the cart before the horse here. After dubiously identifying gang violence as one of the key problems facing children in Britain, it goes on to explain a system that it has devised to alleviate the burden for parents and guardians. Confronted by the spectral presence of ‘kids with guns’, the NSPCC has responded with a 24-hour freephone helpline for worried parents.

This appeal to concerned parents betrays a deep-seated social conservatism at the heart of this new project. The reason the NSPCC finds gangs so barbaric is not solely because of the effect they have on vulnerable children, but because of their distasteful and anti-social presence in Britain’s cities and towns. Citing the involvement of children in gangs is a way of policing the idle young people who play alienating music from garish cars. The charity conflates the urban youth culture that their patrons find unseemly with the violent gang culture that affects very few children. In doing so, it does both groups a huge disservice. The cultural association and congregation of groups of young people is criminalised by a silent army of net-curtain-twitching vigilantes. And the few young gang members who genuinely need the charity’s help are offered the meagre comfort of a 24-hour phoneline.

Jack Prescott is a spiked intern.

Who funds spiked? You do

We are funded by you. And in this era of cancel culture and advertiser boycotts, we rely on your donations more than ever. Seventy per cent of our revenue comes from our readers’ donations – the vast majority giving just £5 per month. If you make a regular donation – of £5 a month or £50 a year – you can become a and enjoy:

–Ad-free reading

–Exclusive events

–Access to our comments section

It’s the best way to keep spiked going – and growing. Thank you!

Comments

Want to join the conversation?

Only spiked supporters and patrons, who donate regularly to us, can comment on our articles.