The Goddard Inquiry: therapy, not justice

This huge inquiry into child abuse has nothing to do with truth.

Want unlimited, ad-free access? Become a spiked supporter.

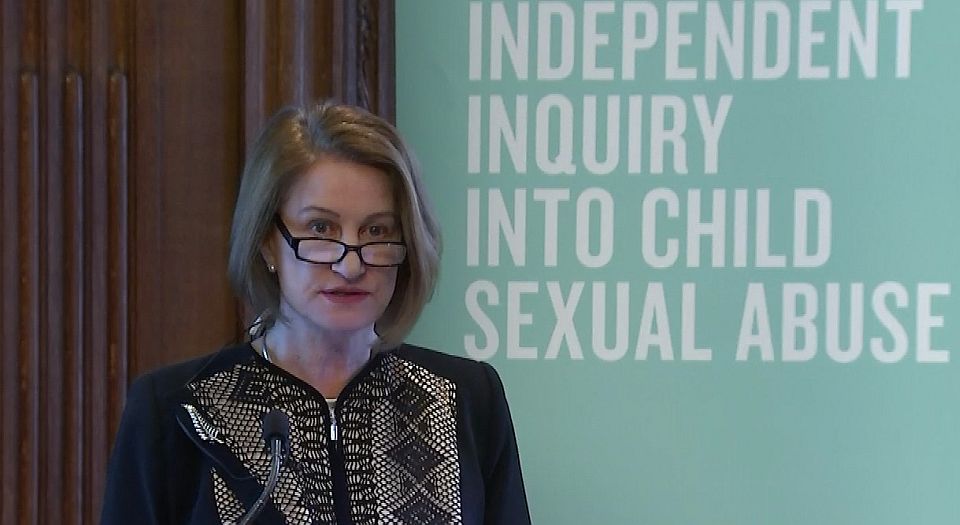

Last week, more details were announced about the UK’s Independent Inquiry into Child Sexual Abuse (aka the Goddard Inquiry). Justice Lowell Goddard, a member of the judiciary of New Zealand who was appointed chair of the inquiry in 2014, announced what the ‘first 12 investigations’ of the inquiry would focus on.

These initial investigations will cover, among other things, the Roman Catholic and Anglican Churches and the local councils of Nottinghamshire, Rochdale and Lambeth. Goddard indicated that these investigations represented the ‘first phase’ of the inquiry’s work and were ‘by no means the total of the work we intend to conduct’. In fact, Goddard has indicated in the past that the remit of the inquiry will include both public and private institutions throughout the UK, with some investigations looking back over ‘many decades’. While Goddard herself gave assurances that the inquiry would conclude within five years, many think this is unrealistic — they estimate that it could take as long as 10 years.

The Goddard Inquiry was announced by home secretary Theresa May in 2014, in the wake of the Jimmy Savile scandal. It aims to expose institutions’ past failures and make recommendations for how to improve child-protection mechanisms in the present. Of course, Goddard is going to have to work hard to surpass the litany of child-protection measures that have been introduced in recent decades. CRB (now DBS) checks and a vast array of powers enabling the criminal courts to disbar people from working with children are just some features of the contemporary framework of anti-abuse law.

This framework itself is the product of earlier inquiries – most notably, the Victoria Climbié Inquiry, which led to the establishment of the Office of the Children’s Commissioner and the passing of the 2004 Children’s Act. The anticipated length of this new inquiry further undermines the idea that it will serve any practical purpose. After all, if we are in the middle of an ongoing child-abuse epidemic, as campaigners claim, then surely we need these ‘recommendations’ right now, not in a decade’s time?

Far from making children safer, this inquiry will merely add to the contemporary panic around child abuse, which continues to corrode the relationship between adults and young people. The last thing we need is more scaremongering. Under new government plans, children as young as 11 will have to be taught about sexual consent. The NSPCC is also involved in educating children about the dangers of abuse, claiming on its website to have visited over 2,000 schools up and down the country. We are often told by children’s charities that the ‘vast majority of child abuse goes unreported’ and that the true extent of abuse remains hidden ‘behind closed doors’. This is all despite the fact that the evidence for such claims is extremely thin and is contained in reports produced by child-abuse campaigners themselves. Far from ignoring child abuse, or trying to ‘sweep it under the carpet’, contemporary society is more obsessed with it than ever before. Indeed, the danger of sexual abuse is among the first things we now teach children about sex and relationships. Do we really need a public inquiry to make us ‘more aware’ of child abuse?

Where previous inquires at least helped to establish the facts of particular cases for the purpose of making recommendations, truth has been the first casualty of the Goddard Inquiry. As part of the so-called Truth Project, complainants will give evidence in private, many avoiding the process of cross-examination altogether. What’s more, those giving evidence to the inquiry, who claim to be the victims of abuse, will not be referred to as complainants, or witnesses, but as ‘survivors’. The truth of their testimony, it seems, will be assumed. These individuals held enormous sway over the inquiry’s chairperson selection process, with two previous chairs rejected because of survivors’ concerns about bias. This inquiry is not about getting at the truth – it’s about lending official recognition to people’s experiences and providing them with emotional closure.

The purpose of the Goddard Inquiry, then, is not practical, but therapeutic. It will do nothing to provide justice to genuine victims of abuse. Indeed, it ditches the difficult task of delivering justice altogether in favour of facilitating a hollow, state-sponsored talking shop. While it has little hope of developing any novel recommendations for child protection, it will be very effective in stoking up and maintaining our unhealthy obsession with child sexual abuse – an obsession that is proving deeply harmful to the relationship between children and adults.

Luke Gittos is law editor at spiked, a solicitor practicing criminal law and convenor of the London Legal Salon. He is the author of Why Rape Culture is a Dangerous Myth: From Steubenville to Ched Evans. Why Rape Culture is a Dangerous Myth: From Steubenville to Ched Evans. (Buy this book from Amazon(UK).)

You’ve hit your monthly free article limit.

Support spiked and get unlimited access.

Support spiked and get unlimited access

spiked is funded by readers like you. Only 0.1% of regular readers currently support us. If just 1% did, we could grow our team and step up the fight for free speech and democracy.

Become a spiked supporter and enjoy unlimited, ad-free access, bonus content and exclusive events – while helping to keep independent journalism alive.

Monthly support makes the biggest difference. Thank you.

Comments

Want to join the conversation?

Only spiked supporters and patrons, who donate regularly to us, can comment on our articles.