The anti-politics of protest

Ivan Krastev’s Democracy Disrupted lays bare the limits of the global protest movement.

Want unlimited, ad-free access? Become a spiked supporter.

‘We’re in the middle of a revolution caused by the near collapse of free-market capitalism combined with an upswing in technical innovation, a surge in desire for individual freedom and a change in human consciousness about what freedom means.’

– Why It’s Kicking off Everywhere, Paul Mason, 2012

‘As night fell over Paris, thousands of people sat cross-legged in the vast square at Place de la République, taking turns to pass round a microphone and denounce everything from the dominance of Google to tax evasion or inequality on housing estates.’

– ‘Nuit debout protesters occupy French cities in revolutionary call for change’, Guardian, 8 April 2016

Following the financial crisis of 2008, it does sometimes feel as if we have entered a new era of global protest. Of course, there appears to be a world of difference between France’s Nuit Debout movement and, say, the Arab Spring. These are very different countries with very different political contexts. But, as Ivan Krastev argues in his short but insightful book, Democracy Disrupted, the protests do share common elements: they are often social-media protests, Blackberry and Twitter revolutions; they mostly lack a specific ideology or coherent political programme; and they lack clear leaders.

In sum, Krastev argues, this new mode of protest involves forms of participation without representation, be it in the shape of a party, or a leader. Indeed, these protests often actively eschew representation as being part of the corrupt old order, the broken politics. Krastev argues that this eschewing of representation makes it increasingly difficult to assess the success or failure of these protests. After all, in most cases, there seems to be little electoral impact, and the status quo quickly returns. This is an important insight. Without representation, the key device of modern democracy, protests go nowhere.

Peter Mair’s Ruling the Void (2013) helps us understand the importance of political representation. Within Western democracies, the mediation between the governed and the government has historically been realised through representative forms of democracy. Representation has therefore long allowed citizens to exercise their collective power and influence on the state. Indeed, the party system of representation has allowed citizens into the state. Representation has allowed what the political scientist Paul Whiteley evocatively calls ‘the invisible handshake’ between the rulers and the ruled; we, the citizens, accept that the state is legitimate, while the state also accepts that democratic legitimation is fundamental for governing (1). It is through representation that citizens can identify and act as a collective.

But, as Mair argues, over the past few decades there has been a hollowing out of Western democracy, an attenuation of the links between the governed and the government. In particular, representation is weakening as citizens back away from formal methods of representation and the political class retreats into the state.

This is a significant shift. Western democracies, resting as they do on popular struggles for ever greater representation, developed as representative democracies. Even younger democracies, such as Russia or the former Warsaw Pact states, have adopted party-political representative systems. So if, as Democracy Disrupted argues, the contemporary global protest movement eschews representation, it simultaneously rejects the prevailing political system. Yet what is not clear is what the protesters want to replace representative democracy with. The protest movement is, as Krastev puts it, a shared experience without a collective identity.

Krastev goes further. He argues that much of the global protest movement is non-political, resembling archaic forms of protest in which groups of people had the power to withdraw from the political system but nothing more. The politics of contemporary protest is the power to refuse, the power to reject. As Krastev writes:

‘What seems clear are a series of aporias. The protesting citizen wants change, but he rejects any form of political representation. He longs for political community, but he refuses to be led by others. He is ready to take the risk of being beaten or even killed by the police, but he is afraid to take the risk of trusting any party or politician. He is dreaming of democracy, but he has lost faith in elections.’

It is a global movement of ‘venting’: we update our Facebook status, or send an angry tweet, and then go back to our lives. It is a cry of frustration, a form of exit politics, that does not challenge the status quo. Thus Krastev argues that far from challenging the system, as hopeful commentators such as Paul Mason have argued, these protests can be seen as a legitimation of the system (albeit in a problematic way). They are a kind of performance of democracy.

Still, the protests are real, and do tend to send political elites into a panic. One of the problems within a state like Russia is that much of the political class refuses to believe these protests can be other than externally funded. Which is understandable given the US, in particular, has a long history of funding opposition groups, armies, jihadists, etc, the world over. But the anti-establishment movement is too broad, too common to too many countries, to be understood as an American intervention. Moreover, we see it manifest in the US, too, with the phenomena of Donald Trump and Bernie Sanders. Just as desperate EU political elites love to cry ‘Putin!’ to explain the rise of European anti-establishment parties, rather than look to their own behaviour, so Russian political elites prefer to blame everything on outside intervention, rather than their own failings.

More broadly, there is an increasing sense among citizens of the irrelevance of governments and elections. Governments might change, but policies will not, runs the common sentiment. Political parties tend to meet mostly now on the centre ground, and politicians have less power than they did for most of the 20th century, when, as part of the postwar consensus, they used national economic instruments such as fiscal and monetary policy to achieve certain social and political outcomes. Today, national governments embrace the mantra of There Is No Alternative, and accept stagnating wages, a decline in productivity and a rise in credit as inevitable.

The avowed impotence of the political class reinforces popular distrust towards its members. After all, if politicians say to citizens that ‘our hands are tied by the forces of globalisation’, then what precisely is the point of politicians? Thus, facing the distrust and contempt of the electorate, politicians have sought out other means of governing away from the angry plebs, the most notable being the European Union.

Democracy Disrupted was written before the Brexit vote, but Krastev’s insights hold. Brexit might have stemmed from a rejection of ‘politics as usual’, a rejection of the political class and of a sense that political decisions are now made far away from the people. But it also has the potential to turn into something more concrete. That’s because, at some point, it will involve concrete political decisions, choices and policies. Brexit could well take a more concrete and old-fashioned political form.

In Europe, we have seen the rise of populist, anti-establishment and anti-EU parties, some explicitly nativist, such as the Front National in France, and some more complex, such as the Five Star Movement in Italy, UKIP in the UK or Podemos in Spain. But even here, these new parties, while having a traditional appearance, lack that old thread between the citizens, as social collectives, and the party. These new parties represent a different, fragile and unpredictable form of the relationship between the citizen and the state.

At the moment, then, it is unclear what form our political future will take – as Gramsci wrote, the old is dying and the new cannot be born. But Krastev provides us with a good idea of what the new might look like.

Tara McCormack is a lecturer in international politics at the University of Leicester.

Democracy Disrupted: The Politics of Global Protest, by Ivan Krastev, is published by University of Pennsylvania Press. (Buy this book from Amazon(UK).)

(1) Political Participation in Britain, by Paul Whiteley, Palgrave Macmillan, 2011, p10

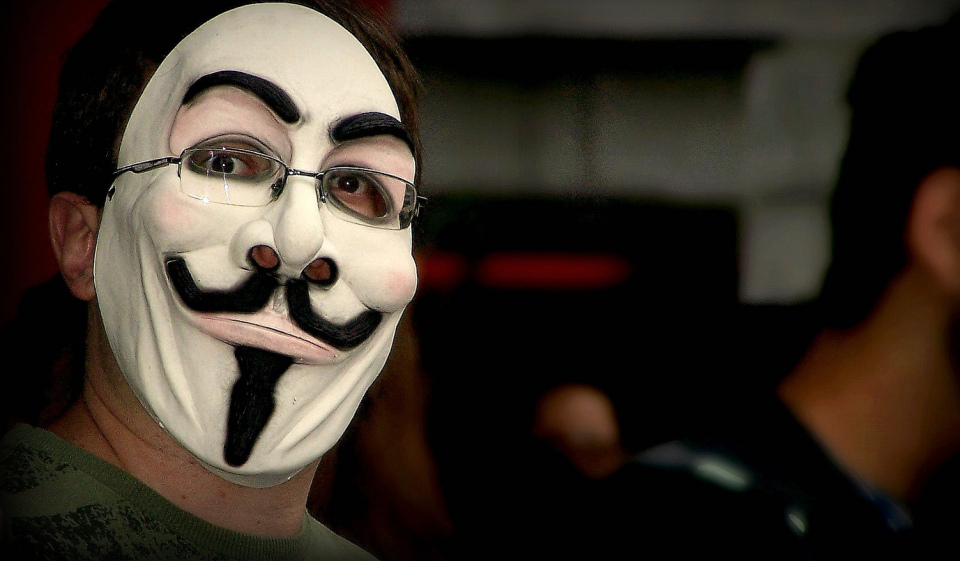

Picture by: Daniel Zahini H, published under a creative commons license.

You’ve hit your monthly free article limit.

Support spiked and get unlimited access.

Support spiked and get unlimited access

spiked is funded by readers like you. Only 0.1% of regular readers currently support us. If just 1% did, we could grow our team and step up the fight for free speech and democracy.

Become a spiked supporter and enjoy unlimited, ad-free access, bonus content and exclusive events – while helping to keep independent journalism alive.

Monthly support makes the biggest difference. Thank you.

Comments

Want to join the conversation?

Only spiked supporters and patrons, who donate regularly to us, can comment on our articles.