Sisi: the West’s favourite dictator

Egypt is further away than ever from the aspirations of the Arab Spring.

Want to read spiked ad-free? Become a spiked supporter.

It is August 2013, a month after then general Abdel el-Sisi had led a coup d’etat against Egypt’s first democratically elected leader, the Muslim Brotherhood’s Mohamed Morsi. Morsi’s supporters had not given up. They were still protesting against the armed overthrow of the man Egyptians had voted for the previous year. But, after six wearying weeks of battling Egypt’s security forces, they had retreated to Rab’a al-Adawiya square. There, with makeshift medical facilities available, they sought respite.

On 14 August this all came to a bloody end. Personnel carriers, bulldozers, ground troops and snipers entered the square from each of the four main entrances, launched tear gas and opened fire. Between 900 and 1,000 Morsi supporters were killed over the following few hours.

This weekend, an Egyptian court finally ruled on the Rab’a massacre. But it didn’t convict anyone from the police and army. No, it convicted survivors of the massacre and supporters of Morsi, sending nearly 400 to prison for over 10 years each, and sentencing 75 members and affiliates of the Muslim Brotherhood to death. Amnesty International was right to call it ‘a grotesque parody of justice’.

But then injustice is par for the course in Sisi’s Egypt. After its brief moment in the democratic sun, following the overthrow of General Mubarak in 2011, Egypt has become, if anything, far more autocratic, repressive and intolerant since Sisi’s coup in 2013 than it was even under the military dictatorship of Mubarak.

The National Security Agency, which is effectively Mubarak’s hated Security Services revamped and rebranded by Sisi in 2013, now acts with brutal arbitrariness, torturing confessions out of perceived threats to the state, and disappearing others. What legal protections there have been for those caught in the security service’s net have been ridden over by the reinstatement of the infamous Emergency State Security Courts, which can pass sentences with no chance of appeal. Needless to say, many political detainees have passed through these courts. As it stands, it is thought that there are 40,000 political detainees in Egyptian prisons.

On top of this brutal crackdown on anything resembling dissent, Sisi’s government has also imposed an anti-protest law; amended the criminal code to allow for pre-trial detentions of up to two years; and attempted to purge the public sphere of any means of dissent, imprisoning journalists and regulating social media. Yes, there have been elections since the overthrow of Morsi. But given that leading opposition groups, including the Muslim Brotherhood, have been banned, there is no electoral alternative to Sisi. Little wonder, then, that in presidential elections in 2014 and in April this year, Sisi has won over 90 per cent of the vote (albeit on a turnout of about 40 per cent).

Egypt is a nation ruled by and through force. It is a nation in which the state can carry out extrajudicial killings with impunity, can disappear people at will, and enmesh others in the grindingly slow, byzantine proceedings of court and prison house. And it is a nation in which the survivors of a massacre can be sentenced to death.

And yet, despite the grim autocracy now prevailing in Egypt, Western states have done nothing but cosy up to it. This regime that is as illiberal and brutal as that of Assad’s in Syria has often been celebrated by governments in the US and Europe. So the news that Sisi had won this year’s presidential election by a margin that, had it been achieved by the likes of Robert Mugabe in Zimbabwe or Saddam Hussein in Iraq, would have prompted derision, was greeted instead by backslapping. Congratulations were offered by the White House. British prime minister Theresa May praised Sisi for taking ‘Egypt further along the path of democratic transition’, which is one way of describing one-party rule grounded on military force.

To crown the West’s embrace of Egypt, President Donald Trump, sometime scourge of ‘the murderous dictatorship’ of Iran, seemed positively delighted, during Sisi’s trip to the US last year, to be in the company of real-life murderous dictator President Sisi. ‘I just want to let everybody know in case there was any doubt that we are very much behind President Sisi’, licked Trump. ‘He’s done a fantastic job in a very difficult situation. We are very much behind Egypt and the people of Egypt.’ Trump even complimented Sisi on his shoes, presumably ignoring the human face they were stamping on.

The double standards are striking, but not surprising. For a start, Egypt is deemed a strategic ally by Western nations in whatever the latest iteration of the decade-long ‘war on terror’ is now called, the logic of which Sisi himself uses when crushing domestic opponents on the grounds that they are terrorists. Egypt is also important economically, especially for Britain, which is the largest foreign investor in Egypt and responsible for 40 per cent of its foreign investment. And, above all, Egypt in 2011, in the democratising throes of the Arab Spring at its height, frightened the West. Or, more accurately, Egyptian people, and who they might vote for, frightened the West. That they eventually did elect Morsi, the Islamist Muslim Brotherhood leader, confirmed those worst fears. And so, when anti-Morsi protesters gathered in Cairo’s Tahrir Square in June 2013, urging on the military, Western commentators cheered and Western leaders breathed a sigh of relief. Order restored. Then US secretary of state John Kerry praised Sisi for ‘restoring democracy’. Baroness Ashton, the EU’s then vice president, said the coup was part of the ‘journey [towards] a stable, prosperous and democratic [future]’.

And what a journey it has been. Speech stifled. Dissenters disappeared. And death sentences passed on political opponents. Under Sisi, Egypt is farther away than ever from the aspirations of the Arab Spring. And closer than ever to Western states.

Tim Black is a spiked columnist.

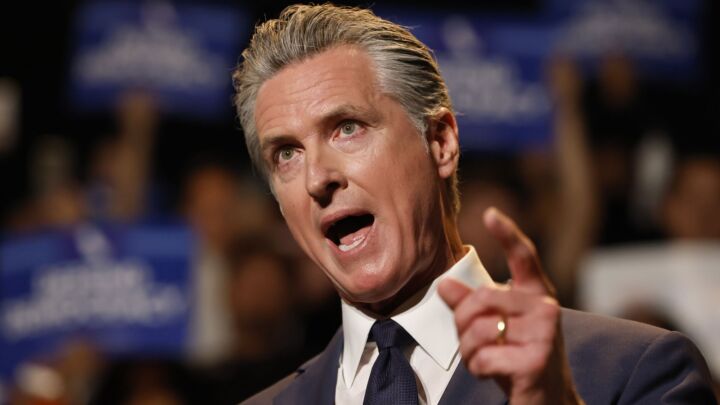

Picture by: Getty

Who funds spiked? You do

We are funded by you. And in this era of cancel culture and advertiser boycotts, we rely on your donations more than ever. Seventy per cent of our revenue comes from our readers’ donations – the vast majority giving just £5 per month. If you make a regular donation – of £5 a month or £50 a year – you can become a and enjoy:

–Ad-free reading

–Exclusive events

–Access to our comments section

It’s the best way to keep spiked going – and growing. Thank you!

Comments

Want to join the conversation?

Only spiked supporters and patrons, who donate regularly to us, can comment on our articles.