Don’t blame LaBeouf for demeaning rape

It was feminists who blurred the lines between rape and sex.

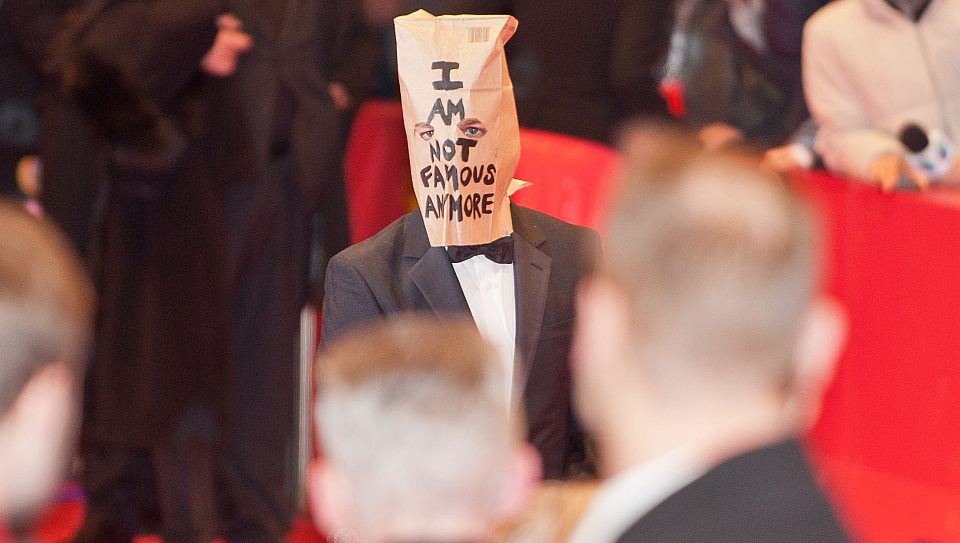

American actor Shia LaBeouf performed his ‘existential crisis’ in a one-man art show entitled #IAMSORRY at a Los Angeles gallery back in February. Now, as news emerges that LaBeouf was allegedly raped by one of the attendees at his show, it seems that his second public performance has now begun, but this time with a much bigger audience.

Such is the hunger for rape scandals among the crowd of feminists and the broadly PC that they leapt upon LaBeouf’s interview with Dazed magazine, in which he briefly asserts that a member of the public ‘stripped my clothing and proceeded to rape me’. It is important to note that directly after his confession, LaBeouf mused about ‘finding my self through these projects I’m exploring’, and tried to secure a plug for one of his art pieces.

The internet is currently divided over LaBeouf’s claims. On one side there is Piers Morgan, who thinks LaBeouf’s rape claim is ‘a load of absolute baloney’. And, on the other, there are the usual feminist Guardian writers, using ‘[LeBeouf’s] clear, personal testimony’ to continue their fight against all misbelievers of rape.

But what is really at stake here is the shift in the meaning of rape. It is not, as Morgan contends, LaBeouf who has demeaned the seriousness of rape. No, that has been accomplished by assorted feminist campaigners and activists determined to widen the scope of what constitutes rape. It is no longer simply an identifiable injustice punishable by law – rape is now often equated with anything sexually unpleasant. It is this that has diminished the seriousness of rape – the conflation of rape with almost any regrettable sexual encounter.

However, there is a clear difference between drunkenly getting into bed with someone, however bitterly regretted the morning after, and being physically forced into having sex. There is a difference between being stripped naked during a performance art exhibit and being physically forced into having sex. The difference is the element of physical violence. And it’s that which ought to be integral to a definition of rape. Without it, there is space for young women to believe that it is possible even to be figuratively raped.

Such is the growing confusion over what constitutes rape that some universities are even running consent classes and encouraging young people to acquire the verbal equivalent of permission slips during sex. It is as if feminists think they have to educate young people on how not to rape each other. But what these interventions really do is draw the law and other external authorities into the messy, trial-and-error nature of all sexual encounters.

The current climate of trigger-happy rape claims and the panic over a supposed surge in sexual violence has led to a genuine demeaning of rape and a diminishing of its seriousness. Morgan is at least correct in pointing out the rather obvious fact that in a situation of genuine rape, it is more than likely that LaBeouf would have fought off the offending fan. But if LaBeouf clearly didn’t feel the need to make more of a deal about his seemingly unpleasant sexual encounter, then why did the Twitterati push victimhood on to him, obliging him to sign his name on the list of rape martyrs for the furtherance of feminism?

Rape has become so loose a term that it is casually tossed around like gossip in a school playground. The legal process of dealing with rape does not necessitate a public scandal, nor should it require a heartfelt profession of dismay from the victim. Most importantly, we have to stop conflating unwanted sexual attention in its varying degrees with the violent act of rape. Such a conflation doesn’t mean we take unwanted sexual attention more seriously; it just means we take rape less seriously.

And we really shouldn’t need the artistic confessions of a multi-millionaire in the grip of an existential crisis to teach us what rape is.

Ella Whelan is a writer based in London.

Picture by: Wikimedia Commons

To enquire about republishing spiked’s content, a right to reply or to request a correction, please contact the managing editor, Viv Regan.

Comments

Want to join the conversation?

Only spiked supporters and patrons, who donate regularly to us, can comment on our articles.