Revisiting Harper Lee’s moral universe

To Kill a Mockingbird is a paean to universalism.

Want to read spiked ad-free? Become a spiked supporter.

Harper Lee, the author of To Kill a Mockingbird, is gone, and so, some would argue, is her legacy in the wake of the publication of her second novel Go Set a Watchman last year. Until that time, To Kill a Mockingbird, and the classic film of the same name, occupied a unique position in American culture.

Published just before the birth of the civil-rights movement, To Kill a Mockingbird became a sort of primer that taught US society about the abiding injustice of racism, and the character Atticus Finch (forever pictured as Gregory Peck) became a moral model. Here was one good man standing up against the backwardness of Southern culture. His definition of courage – ‘when you know you’re licked before you begin but you begin anyway and you see it through no matter what’ – inspired generations of activists, lawyers, writers and even parents, who all tried to emulate his quiet authority, many naming their children after him.

This is why last year’s publication of Go Set a Watchman, in which it was revealed that Atticus was a segregationist, felt so jarring to so many. Critics panned the book. Some people questioned whether Lee had been manipulated into publishing it. Others refused to read it on principle. In at least one instance, parents changed their child’s name from Atticus to something else. For the cynics, the new book confirmed what they thought all along: that To Kill a Mockingbird was just another ‘white saviour’ story, a narrative of white privilege in which black people are merely props to make racists feel better about themselves.

And yet, rereading Mockingbird, neither the classic interpretation of the book nor its reassessment in the light of Watchman seems quite right. As tempting as it is to see the book through the prism of race, Lee seems to be trying to do something more. There’s a clue in an interview she gave to the Birmingham Post Herald in 1962. ‘My book has a universal theme’, she explained. ‘It’s not a “racial” novel. It portrays an aspect of civilisation, not necessarily Southern civilisation.’

From this perspective, race is only one aspect – though perhaps the most important aspect – of a single moral universe. Lee’s book is a study in what she called in a 1964 radio interview ‘the rich social patterns of small-town, middle-class Southern life’: the endless grouping and ungrouping of folks, the pecking order between rich and poor, between generations, between Maycomb’s tribes – Ewells, Finches and Cunninghams, Methodists and feet-washing Baptists, blacks and whites.

The recurring question is: how do we overcome those divisions and rediscover our common humanity? ‘A mob’s always made up of people, no matter what’, Atticus says of the group of men who turned up at the jail intending to lynch Tom Robinson. ‘So it took an eight-year-old child to bring ‘em to their senses, didn’t it? That proves something – that a gang of wild animals can be stopped, simply because they’re still human.’ Even in Maycomb, even in the midst of injustice, there is hope: the one man on the jury who tried to hold out against convicting Tom Robinson was also one of the men in the mob at the jail.

Today, Lee’s Maycomb seems remote, but not for the obvious reasons. It is not just the end of ladies’ clubs or Jim Crow, of stable marriages or the homogenisation of culture, that makes Mockingbird seem so distant. At a time when identity dominates society’s outlook, tribes are just tribes and groupings are just intersections of identities, there is and can never be a shared moral universe. In retrospect, the book itself, and especially Atticus, became part of a particular brand of elite identity, defined in opposition to the various varieties of plebs with whom Lee had so much sympathy. This is why he went, almost overnight, from cherished icon to the ultimate symbol of white privilege.

This loss of a sense of the universal is no small thing. When Martin Luther King said ‘the arc of the moral universe is long, but it bends toward justice’, he had in mind the same universe as Harper Lee. Today, without that sense of a moral universal, we cannot walk around in someone else’s skin – in fact, it would be an affront. There can be no justice or any possibility of it, no pull of attraction compelling us to overcome the limitations of identity, only a sort of conformity enforced by the enlightened few.

Still, like all great art, Mockingbird is powerful and compelling. By walking around Maycomb in Scout’s skin, our own world, our own tribes, come a little more into focus. Like the half-remembered story Scout tries to tell Atticus as he puts her to bed:

‘“An they chased him ‘n’ never could catch him ‘cause they didn’t know what he looked like, an’ Atticus, when they finally saw him, why he hadn’t done any of those things. . . Atticus, he was real nice. . . ” His hands were under my chin, pulling up the cover, tucking it around me.

‘“Most people are, Scout, when you finally see them.”’

Lee’s book still reminds us that hope of redemption is always there. Even if we don’t always see it.

Nancy McDermott is a writer based in New York.

Who funds spiked? You do

We are funded by you. And in this era of cancel culture and advertiser boycotts, we rely on your donations more than ever. Seventy per cent of our revenue comes from our readers’ donations – the vast majority giving just £5 per month. If you make a regular donation – of £5 a month or £50 a year – you can become a and enjoy:

–Ad-free reading

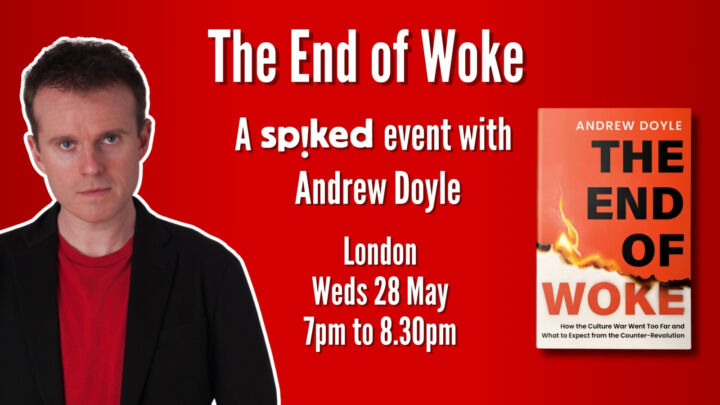

–Exclusive events

–Access to our comments section

It’s the best way to keep spiked going – and growing. Thank you!

Comments

Want to join the conversation?

Only spiked supporters and patrons, who donate regularly to us, can comment on our articles.