Not all acts of mass murder are terrorism

Calling Vegas 'terrorism' is another way of downplaying the Islamist threat.

Want unlimited, ad-free access? Become a spiked supporter.

What’s driving the demand to brand the Las Vegas massacre an act of terrorism? As soon as it was revealed that this mass murderer, this slaughterer of 59 music fans and injurer of an eye-watering 525 more, was a white man, the following cry went out from the so-called liberal set: ‘This must be called terrorism.’ It’s no good, they said — and it might even be racist — to refer to this barbarism as simply mass murder, or to describe the shooter Stephen Paddock as a ‘lone wolf’, or to diminish his evil by calling him ‘mad’. No, just as we call ‘brown people’ terrorists every time they carry out an act of mass violence, so we must call Paddock a terrorist, too, columnists and the Twitterati insisted. The challenge was set: are you going to be racist and call this act ‘mass murder’, or are you going to be progressive and decent and call it ‘terrorism’?

This balefully predictable discussion, this wail of ‘white men can be terrorists, too!’, now follows every mass shooting or act of nihilistic or psychotic violence, particularly in the US. A vile racist or unhinged loner carries out a bloody act against his fellow citizens and the media set instantly issue the demand: ‘Call it terrorism.’ Of course it’s true white men can be terrorists, as attested to by various movements and acts in 20th-century Europe and occasionally in modern America. But this new rush to attach the T-word to every large act of violence, to all forms of hateful mass assault, is not driven by a serious, analytical desire to understand and explain terrorism; no, its impulse is moral evasion, an urge to take the heat off Islamist violence and distract the public eye from what anyone with an ounce of intellectual honesty would recognise as the only genuine, organised terrorist threat in the 21st-century West: radical Islamism.

You could almost hear the sigh of relief when it was revealed the mass murderer in Vegas was a white man, and a 64-year-old former accountant to boot. A strain of ‘phew’ ran through the early political commentary and online discussion, as people realised they wouldn’t have to talk about Islamism again. Even better, they could consciously, actively, keenly diminish discussion of Islamist violence, and of the very problem of Islamist violence, by politicising the Vegas massacre and putting it on a morally equivalent par with the Islamist threat. A writer for the Washington Post lamented the ‘messages’ that ‘command us’ — not really us, but them, the gullible people — to associate terrorism with Muslims and to ‘neglect hateful, armed white terrorists’. ‘Stephen Paddock was obviously a terrorist. But because he’s white, we don’t call it that’, said a GQ columnist. Rolling Stone, like many others, spied racism in the unwillingness to call mass shootings ‘terrorism’. It is ‘driven by racism’, said the staid rock mag: ‘We call white shooters “lone wolves” and not “terrorists”.’

Yet anyone who has even a basic grasp of the English language knows there is a difference between mass murder and terrorism. Not all acts of mass murder are terrorism. Dennis Nilsen, the deranged gay serial killer of 1970s Britain, was not a terrorist. Nor was Charles Manson, who killed groups of people. Nor was Brenda Ann Spencer, the then 16-year-old shooter who fired on Cleveland Elementary School in 1979 and inspired the Boomtown Rats hit ‘I don’t like Mondays’ (which was the reason she gave for her killings). Sometimes mass murder is just — perhaps ‘just’ should be in quote marks, given all these acts are awful — mass murder. Terrorism is different. Terrorism is the use of violence to a political end, usually by people who associate themselves with an ideological organisation. And that political end is more often than not the weakening of a society’s sense of itself, the corrosion of a society’s confidence, the use of fear and violence to weaken a society that is viewed by the violent actor as evil or wrong or just too liberal. Terrorism is not just mass murder; it is mass murder for a reason.

But people know this. Surely? They surely know that when an angry, disgruntled man or some nihilistic youths take it upon themselves to visit violence upon their parents or schoolfriends or people out shopping, that is different to the concerted, ideologically justified campaign of terrorism pursued by radical Islamist groups in recent years, which has killed more than 450 people in Europe alone since 2014. It benefits no one to elide mass murder and terrorism; to erode the linguistic and moral distinction between different forms of violence and the different impacts they have, and are designed to have, on society. Actually, scrap that: there are people who benefit from such wilful elisions — those who have strangely devoted themselves to the task of downplaying the problem of Islamist terrorism or any open, frank discussion about how Islamist terrorism might be confronted.

This is the fuel to today’s deeply dishonest, defensive and linguistically-challenged insistence that we refer to all sorts of mass killings and shootings as ‘terrorism’: a desire to shift the focus from the 21st-century terrorism problem, a low, evasive instinct to defuse debate and certainly concern or anger with actual terrorism. It is a search, a rather desperate search, for moral equivalence, for other forms of violence that can be pointed to, cynically, as a way of saying: ‘See? Terror is everywhere. It isn’t only coming from one ideology or people of a particular religious background.’ It is moral equivalising to the end of silencing, or at least temporarily shushing, serious or heated debate about what we might call the ISIS ideology: a key pusher of backward ideas which, whether we like it or not, appeal to relatively signifiant sections of our societies and which entice some of them towards committing mass acts of ideologically inspired violence. This is a problem that needs free and frank addressing, but such discussion is always discouraged. ‘Don’t look back in anger’, we’re advised after every Islamist atrocity.

The amount of intellectual and moral energy that is now devoted to discouraging discussion of Islamist terrorism is extraordinary. A whole new castigating language has been created to demonise such discussion — you’re ‘Islamophobic’ if you think there’s a problem; you’re ‘hard right’ if you are concerned about the separation of some Muslim communities from mainstream society. And after attacks there are concerted efforts to cultivate passivity rather than debate, quiet reflection rather than analytical interrogation. Lay a flower, cry, feel sad, change your profile pic, and then crack on with life — and, remember, never look back in anger. The reluctance to confront the terrorism problem has now reached a level where the word terrorism itself has effectively been redefined — to encapsulate more and more forms of violence — and where random mass shootings are almost welcomed by observers because they allow them to dilute the terrorist crisis. This is the stage of intellectual and moral cowardice the 21st-century West has reached — where even a foul, tragic massacre is treated as an opportunity to dissipate moral debate and weaken the moral challenge to Islamist violence.

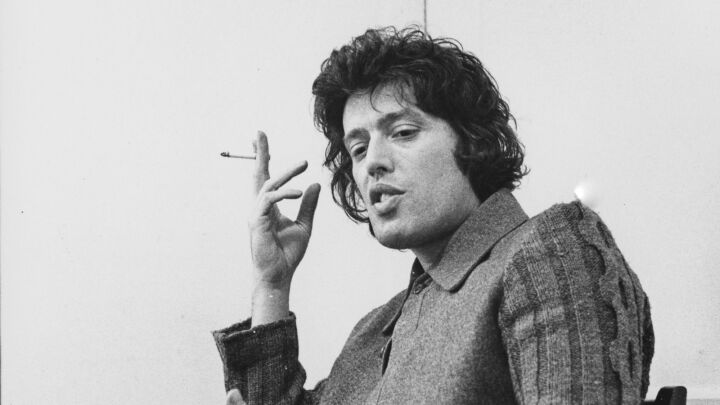

Brendan O’Neill is editor of spiked.

Brendan is speaking at the events ‘Is the left eating itself?’, in NYC on 2 November, and ‘Is political correctness why Trump won?’, at Harvard on 6 November, as part of spiked US’s Unsafe Space Tour. Get tickets here.

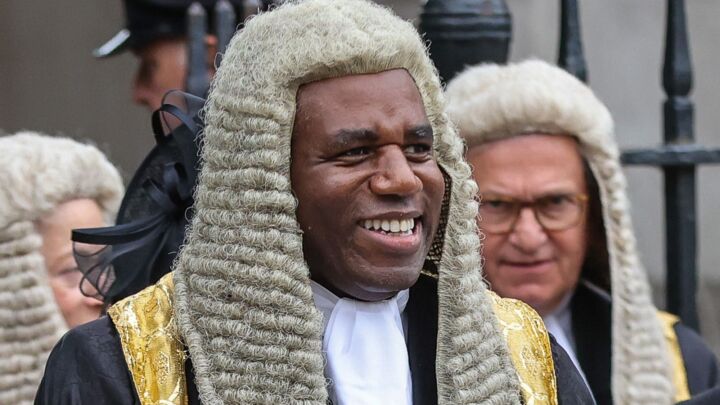

Picture by: Getty

You’ve read 3 free articles this month.

Support spiked and get unlimited access.

Help us hit our 1% target

spiked is funded by readers like you. It’s your generosity that keeps us fearless and independent.

Only 0.1% of our regular readers currently support spiked. If just 1% gave, we could grow our team – and step up the fight for free speech and democracy right when it matters most.

Join today from £5/month (£50/year) and get unlimited, ad-free access, bonus content, exclusive events and more – all while helping to keep spiked saying the unsayable.

Monthly support makes the biggest difference. Thank you.

Comments

Want to join the conversation?

Only spiked supporters and patrons, who donate regularly to us, can comment on our articles.