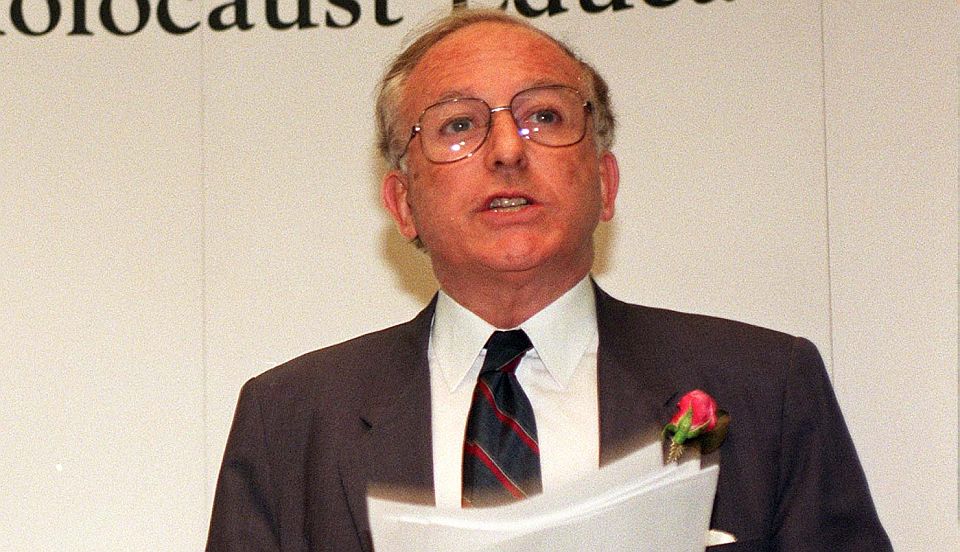

Lord Janner: you can’t try a dead man

It would be a perversion of justice to put the deceased on trial.

Want unlimited, ad-free access? Become a spiked supporter.

The death of Lord Greville Janner, who was due to stand a ‘trial of the facts’ to establish whether child-abuse allegations against him were true, led to the Crown Prosecution Service (CPS) making an unprecedented announcement. For the first time in legal history, the CPS refused to rule out trying Janner on a trial of the facts notwithstanding his death.

Many legal commentators have objected to the CPS’s move. There has been a broad consensus that trying Janner when he is dead could not possibly deliver justice. But it would be a mistake to understand this announcement as an anomaly. In fact, it is an entirely logical outcome of significant trends in criminal-justice reform in recent decades. The first is the trend towards a more victim-centred justice system. The second is the institutional weakness and politicisation of the CPS in the face of child-abuse hysteria. Both of these tendencies have been exacerbated by the recent climate around allegations of child-sexual abuse, which have been described on spiked and elsewhere as a moral crusade.

The needs of complainants and victims have been central to the decision-making around Janner and other cases like his. The most prominent example of the centrality of victims to the official handling of child-abuse allegations is the establishment of the Goddard Inquiry, which gave a public airing to allegations that could not meet the evidential criteria for a criminal prosecution. The initial CPS decision not to prosecute Janner was overturned on review after an independent QC found that there was a ‘public interest’ in having the complainants’ allegations heard in a formal setting, regardless of the fact that the outcome of the proceedings would be a forgone conclusion. This decision demonstrated the strong influence of complainants’ interests on the processes of criminal justice.

The development of a more victim-centred justice system and new tribunals designed to deliver ‘closure’ is not new. An important component of New Labour’s policy on criminal justice, on being ‘tough on crime and tough on the causes of crime’, was the removal of key defendants’ rights in favour of ensuring that more victims felt as though justice had been done.

Jack Straw famously bemoaned the ‘defendants’ rights lobby’ in preventing victims from achieving justice. Since the Nineties, it has been recognised that victims and complainants are no longer ‘mere spectators’ in the justice process. They now have a far greater influence in how proceedings are decided. Today, almost every proposed reform to the justice system is undertaken in the name of improving complainants’ experiences in court. Recent examples include: limiting the ambit of cross-examination; allowing complainants to give evidence in different forums, including over a video link from another room; and permitting complainants to provide the judge with a ‘victim impact statement’, in which they detail the emotional effect the crime had on them. This last development can influence a judge in the sentencing of defendants. The orientation of our criminal-justice institutions around the needs of victims was a significant factor in the decision potentially to put Janner on trial after his death.

The weakening of the CPS and its increased politicisation in the face of child-abuse hysteria is also a significant trend. Several commentators have pointed out that the CPS has become more political in recent years, with the role of director of public prosecutions (DPP) becoming increasingly concerned with managing public perceptions of the justice system. But it is important to recognise the connection between this politicisation and the current climate around child-sexual abuse. It is because of this climate that it has become common for politicians to turn the apparent failings of the police and the CPS into political causes through which they can demonstrate a degree of moral authority. This then forces the CPS and the DPP to make decisions based not on the objective application of the law, but in the name of responding to the moralised allegations of institutional failure.

The most prominent example in recent years was the systemic failings by safeguarding authorities and the police in Rotherham to tackle a network of Pakistani men who were abusing underage girls. The home secretary, Theresa May, was quick to suggest that the Rotherham case was symptomatic of broader societal failings in dealing with child abuse, which then became part of the justification for the Goddard Inquiry. Rotherham police ordered a public investigation into their own handling of the investigation that was widely reported as being indicative of an official abandonment by the state of child-abuse victims.

Rotherham is one of many examples of prosecuting institutions being forced to respond to public allegations of incompetence regarding their dealings with child-abuse cases. In 2014, Manchester police and the CPS both issued public apologies for failing to prosecute former Lib Dem MP Cyril Smith for allegations from the 1970s. The outcome of the allegations against Jimmy Savile was the Met’s report ‘Giving Victims a Voice’, which publicly acknowledged the Met’s own failings with respect to investigating Savile. As failures of state institutions to deal with child-abuse allegations have become so open to public scrutiny, the role of the DPP has become far more politicised. The DPP and CPS are more often concerned with atoning for mistakes of the past than dealing with the problems society faces today.

These dynamics have occurred in the context of the child-abuse panic. The Janner decision is the result of the palpable moral crusade around child abuse initiated by Operation Yewtree. Since the revelations around Savile, a number of politicians and public bodies have become fixated on allegations of child sexual abuse as a moral cause around which to organise public policy. This has led many public figures to continue to emphasise the dangers of child abuse in order to justify further reform. May has suggested that child abuse runs though the country ‘like a stick of Blackpool rock’, warning that the findings of the Goddard Inquiry will mean that ‘we [will] never look at society in the same way again’. A network of experts has established itself as capable of exposing the undercurrent of abuse running through British society. The NSPCC often claims that child abuse is largely underreported and that more early intervention is required to prevent yet more abuse. These panicked portrayals of widespread child abuse are not based on reliable evidence, but instead function to perpetuate a narrative around abuse that makes a decision such as that taken against Janner seem justified.

Of course, some may view these tendencies within our justice system as positive. It is difficult to argue with any change that makes dealing with child abuse more effective. But, as many have now come to realise following the Janner decision, these tendencies do not make dealing with real child abuse easier. Rather, they warp the mechanisms through which genuine justice can be achieved. They place public pressure on our prosecutors to make decisions that fit public-relations purposes. They force the police and prosecutors to become fixated on their performance statistics, meaning that decisions on political cases become driven by a need to improve an overall picture rather than deal with a case fairly and objectively.

Of course the Janner decision is wrong. But it is the result of a number of significant trends that have unfolded in recent decades. If we are to prevent more decisions like the Janner one, we need a thorough reassessment of what the justice system is for and a retreat from the current climate of panic that surrounds allegations of child sexual abuse.

Luke Gittos is law editor at spiked, a solicitor practicing criminal law and convenor of the London Legal Salon. He is the author of Why Rape Culture is a Dangerous Myth: From Steubenville to Ched Evans. (Buy this book from Amazon(UK).)

£1 a month for 3 months

You’ve hit your monthly free article limit.

Support spiked and get unlimited access.

Support spiked – £1 a month for 3 months

spiked is funded by readers like you. Only 0.1% of regular readers currently support us. If just 1% did, we could grow our team and step up the fight for free speech and democracy.

Become a spiked supporter and enjoy unlimited, ad-free access, bonus content and exclusive events – while helping to keep independent journalism alive.

———————————————————————————————————————————–

Exclusive January offer: join today for £1 a month for 3 months. Then £5 a month, cancel anytime.

———————————————————————————————————————————–

Monthly support makes the biggest difference. Thank you.

Comments

Want to join the conversation?

Only spiked supporters and patrons, who donate regularly to us, can comment on our articles.