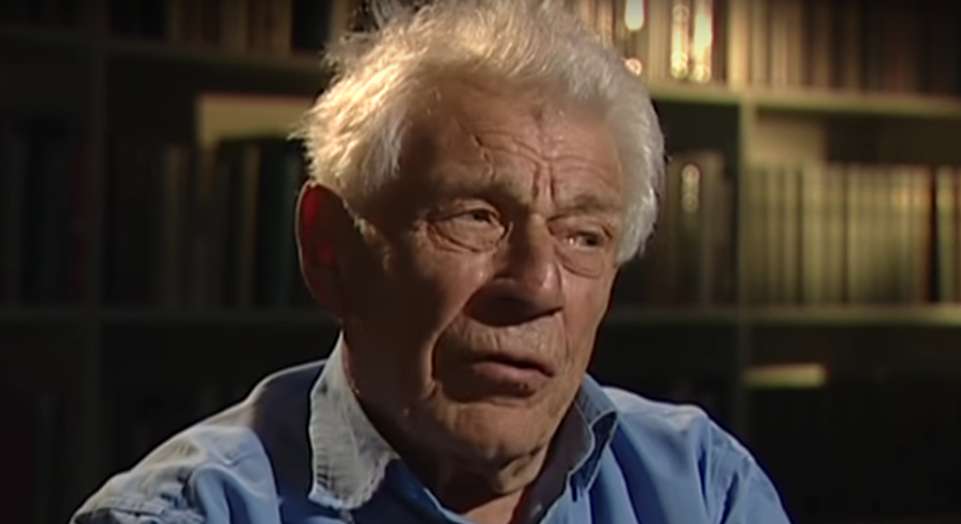

John Berger’s ways of seeing

The art critic and the search for meaning.

Want unlimited, ad-free access? Become a spiked supporter.

Re-reading the work of John Berger, as well as the commentary on his life and influence, I recalled a conversation many years ago with a fellow history student at Oxford. In the middle of another essay crisis — 12 essays in eight weeks — he remarked that writing was much easier as a Marxist because you could use the same argument every time. ‘It is no accident that…’, each essay could begin.

The same cannot be said of Berger, the art critic who died this month. His work is far richer than this and has none of the mechanical and formulaic qualities my fellow student joked about. However, Berger’s concern for historical specificity and his emphasis on the historically defined nature of our own perception, most famously expressed in the landmark TV series and follow-up text Ways of Seeing, could quite readily lend itself to oversimplification. Berger himself was always best as an art critic when he used his own eye to observe and characterise a work rather than as a social theorist with a model to sell.

In his art criticism and his wonderful sociological and anthropological studies, Berger’s understanding was rich, empathetic; almost clinically observant and yet daringly imaginative. I am thinking of essays such as ‘The Storyteller’, which discusses the role of the oral tradition in a society characterised by familiarity and shared experience. Then there’s ‘The Eyes of Claude Monet’, which explores the position of Impressionism in relation to photography and the changed nature of time, memory and our relationship to nature. A personal favourite of mine is ‘A Fortunate Man: The Story of a Country Doctor’ (1967), which, together with the photographs of Jean Mohr, documents three months in the life of a country doctor in the isolated Forest of Dean. It is a profoundly moving account of an extraordinary man and rationalist in deep engagement with the experiences not merely of patients, but of human beings.

Berger’s primary concerns were always experience and meaning. Which meant his work was ideally suited to the precise study of the individual, whether artefact or person. Such study becomes impossible when an abstract schema is imposed. To put it another way, the meaning of the daily experience of people situated in place and time is more universal than any general formula, however supportive of the dispossessed that formula may claim to be. We see and understand both the work and the painter better through such close attention to the individual thing. As Berger himself puts it, we should not think of the artefact as separate from the painter and his response to his own life and times, nor the painter as divorced from his own engagement with the form and substance of his work.

Since their respective landmark TV series Civilisation (1969) and Ways of Seeing (1972), Kenneth Clark and John Berger have been held up as representatives of antagonistic positions. This resurfaced in the discussion of Berger following his death. However, they have more in common than first sight suggests. Both are optimists: Clark through his elucidation of the moment of human possibility in the early Renaissance (1420-1480); and Berger in his seminal essay, ‘The Moment of Cubism’ (1969). In that essay, Berger wrote: ‘I find it hard to believe that the most extreme Cubist works were painted over 50 years ago. It is true that I would not expect them to have been painted today. They are both too optimistic and too revolutionary for that.’

Neither is Clark oblivious to social change, as his cogent and concise description of the Florentine city state, its trading relations and that era’s conceptualisation of the individual makes clear. Berger makes the same points in his own way when he counterposes innovative periods of art with decadent ones.

While it can be said that the sumptuous style of Civilisation has remained more fashionable than the quirky and low-budget Ways of Seeing, it is the argument of Ways of Seeing that has prevailed, and not in a good way. Berger is never in any doubt that technique can be sacrificed to an idea:

‘For the artist, drawing is discovery. And that is not just a slick phrase, it is quite literally true. It is the actual act of drawing that forces the artist to look at the object in front of him, to dissect it in his mind’s eye and put it together again.’

Ways of Seeing was hugely influential. Not only because it contained so much of Berger’s scrupulous attention to technique, innovation and social transformation, but also for its argument that it is too easy, and lazy, to read every work of art and each experience through a single frame of reference. Berger frequently emphasised this in relation to the development of art. He pointed to the swift decline in the quality of Abstract Expressionism: anyone who attended the recent Royal Academy exhibition of expressionist works will have seen how the compelling and moving works of the likes of Rothko soon gave way to vacuous imitation.

The National Gallery’s current exhibition Beyond Caravaggio also demonstrates Berger’s point. It’s a great exhibition, not least for showing how a new insight can become stagey and derivative through the work of others: the Caravaggios are stunning but, as the innovative becomes fashionable, the work of his imitators appears tired and empty.

For this fate not to befall Berger himself, go beyond Ways of Seeing, and read what he had to say about the experience of people and the meaning of things.

Alan Hudson is director of programmes in leadership and public policy at the Oxford University Department for Continuing Education.

You’ve read 3 free articles this month.

Support spiked and get unlimited access.

Help us hit our 1% target

spiked is funded by readers like you. It’s your generosity that keeps us fearless and independent.

Only 0.1% of our regular readers currently support spiked. If just 1% gave, we could grow our team – and step up the fight for free speech and democracy right when it matters most.

Join today from £5/month (£50/year) and get unlimited, ad-free access, bonus content, exclusive events and more – all while helping to keep spiked saying the unsayable.

Monthly support makes the biggest difference. Thank you.

Comments

Want to join the conversation?

Only spiked supporters and patrons, who donate regularly to us, can comment on our articles.