Isaiah vs Isaac: a philosophers’ catfight

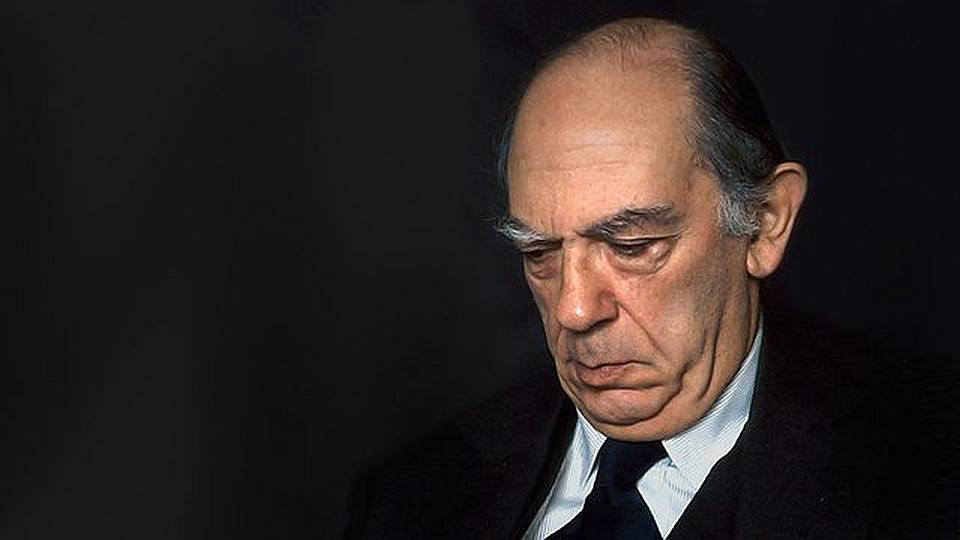

Isaiah Berlin’s run-ins with Isaac Deutscher show what a bitch Berlin could be.

Want unlimited, ad-free access? Become a spiked supporter.

One evening in December 1966, the great American writer and critic Edmund Wilson had Sir Isaiah Berlin over for dinner. And a good time they doubtless had of it, but later that night Wilson recorded in his diary that he found Berlin prone to ‘violent, sometimes irrational prejudice against people’. On the evening in question the object of Berlin’s ire was the philosopher and political theorist Hannah Arendt, whose book about the trial of the Nazi officer Adolf Eichmann, Eichmann in Jerusalem, he excoriated without, Wilson claimed, his ever having troubled to read it.

On that last point at least, Wilson seems to have been wrong. Granted the evidence marshalled in David Caute’s Isaac & Isaiah: The Covert Punishment of a Cold War Heretic, it is fair to conclude that Berlin had not only read Arendt’s bestseller, but had also likely arranged for his close friend John Sparrow, then warden of All Souls College at Oxford, to give the book a kicking in the pages of the Times Literary Supplement. Since TLS reviews were printed without bylines back then, why didn’t Berlin write about the book himself? Because, Caute argues, he had for some reason ‘always avoided referring to Arendt in print’. Privately, though, he was happy to rubbish her work. A few years earlier, he had written Faber & Faber a report on Arendt’s The Human Condition. It opened by telling them he ‘could recommend no publisher to buy the UK rights of this book. There are two objections to it: it won’t sell, and it is no good.’

Fans of Berlin’s waspish wit will relish those last two clauses (invert them, as the logic of the sentence dictates, and the wit is gone), but did Arendt’s most considered work really merit such a stinging rebuke? Did Eichmann in Jerusalem, whose insights into what its subtitle calls ‘the banality of evil’ are still potent, really deserve that TLS hatchet job? To be sure, subsequent research has disproven many of the book’s claims about Eichmann himself. But half a century ago nobody save Eichmann was in a position to know that Arendt’s belief that he was no more than a stupid, anonymous cog in the Nazi machinery was quite wrong.

Caute believes that the antipathy Berlin felt for Arendt was largely explicable by the fact of his fealty to Zionism and her belief that nationalism was past its sell-by-date. But even though history proved Arendt wrong on this count, oughtn’t the philosopher who made his name by arguing that incompatible values can all be valid have been less ready to take offence over the disagreement? Nationalists need not be nasty, but nor is everyone who longs for a better tomorrow willing to worsen the here and now in order to bring it on.

But what of people who lie about yesterday in order to pretend that today is better than it is? Such was the gist of Berlin’s loathing of the historian and journalist Isaac Deutscher. Deutscher ‘worship[ped]’ Lenin, Berlin told Caute one day in March 1963 in the All Souls common room, and his three-volume biography of Trotsky was designed to make its subject look like ‘Jesus on the cross’, his story ‘the great modern tragedy’. Was Berlin, Caute asked, hostile to Deutscher because he remained loyal to Marxism? Not at all, said Berlin, saying that he had the greatest respect for the work of C Wright Mills and Eric Hobsbawm, and that a few years earlier he had supported EH Carr’s candidature at Trinity College. ‘To be a Marxist is a legitimate stance for an academic’, Berlin told Caute, ‘but Deutscher parades as a soothsayer… [Nobody] knows the whole truth – but Deutscher does.’

Just another day in the backstabbing groves of academe? To be sure, though the suspicion Caute harboured that Berlin’s harangue had been prompted by the prospect of Deutscher’s getting a lectureship was right on the money. A few months earlier, when Deutscher had applied for a job as a senior lecturer at the University of Sussex, Asa Briggs and his colleagues in the history department were thrilled, and proposed he be offered a professorship in Soviet Studies. Fine, said Sussex’s vice-chancellor, John Fulton, the job is Deutscher’s – just let me have a word with the board’s external adviser. Except that the board’s external adviser was Isaiah Berlin, and he blackballed Deutscher, telling Fulton that ‘the candidate of whom you speak is the only man whose presence in the same academic community as myself I should find intolerable’.

Fair enough, though Caute’s book, while itself critical of Deutscher’s ideological blindspots, provides sufficient evidence to suggest that Berlin’s loathing of the historian was motivated by more than mere historiography. As with Arendt, only more so, Berlin was predisposed to dislike Deutscher because he was such a fierce critic of Israel and Zionism. What had really fanned fury’s flames, though, was Deutscher’s demolition job of Berlin’s Historical Inevitability in the Observer. Goading Berlin the most, Caute suspects, was the fact that Deutscher found Berlin’s anti-Hegelian tract quite as airless, abstracted and inhumane as anything Berlin had claimed to find in a thousand Marxian screeds. (Caute agrees: his book is worth reading just for its brief but deadly assault on Berlin’s overestimation of the effect ideas have on history.)

Not that Deutscher was alone in dismissing Berlin’s book. Lewis Namier, a friend of Berlin, and one of his closest brothers-in-arms in the war against enlightenment rationalism, also found it rather too theoretical. ‘How intelligent you must be’, he joshed Berlin, ‘to understand all you write!’. Even more tellingly, EH Carr took issue with Berlin’s notion that people who find patterns and logic and order in history are halfway down the road to dictatorship. People who find patterns and logic and order in history, Carr argued, are simply historians – for the fact is that history does not exist independent of the interpretations that are placed on it. Historians are not mere narrators of events. They are explicators of the narrative they themselves create in the act of writing.

Somehow, though, Berlin was able to overlook these other critics. It was Deutscher alone who got it in the throat. Berlin was so offended by his notice that the faithful Zionist took to calling the nationalistic doubter a ‘mangy Jew’. To be fair, Berlin was half aware there might be something irrational about his loathing of Deutscher. ‘I suffer from a profound, perhaps exaggerated antipathy to all his writings’, he wrote in 1959. ‘I think him specious, dishonest, and in any case possessed of some quality which causes some kind of nausea within me.’ There is more, a lot more, like that in the pages of the latest volume of Berlin’s letters, Building.

What there also is is a 1969 letter from Berlin to Deutscher’s widow Tamara (Deutscher died young, aged only 60, in 1967), denying that he had done anything that might have prevented her husband from gaining a posting at the University of Sussex six years earlier. The letter had been occasioned by the publication of just such claims in Tariq Ali’s left-wing newspaper Black Dwarf. Berlin was, of course, lying – precisely the crime he was forever accusing Deutscher of having perpetrated in his books on the Soviet Union. One must, Berlin wrote in a letter to Elena Levin, be ‘either a Dantonist or a Robespierrist and I am quite clear that I am the former and cannot really sit at the same table as the latter’. He might be right about that either/or, but he was kidding himself about which side of the fence he was on. To be sure, lying isn’t the same as sending someone to their death – but the distinction hardly justifies the liar thinking himself heroic. There is simply no moral high ground here, and the reader of Berlin’s letters is surely justified in thinking him neither a Dantonist nor a Robespierrist but a shoo-in for Moliere’s Tartuffe.

Why, though, the need for the lie to Deutscher’s widow? Because while Berlin might not have wanted to sit at the same table as a Robespierrist, he definitely wanted to sit at the best tables in the land. To work one’s way through Building is to be regaled with accounts of one glittering dinner party after another – the bulk of the glitter coming courtesy of Berlin’s chit-chat charm. To see the charm at work, check out Berlin’s letter to Hannah Arendt’s friend Mary McCarthy. Having begun by assuring her that he had had nothing to do with Eichmann in Jerusalem being given a rough ride in the TLS, Berlin segues into jokes about the death of Lord Beaverbrook and his own ‘state of excessive indignation about everything’, before asking whether McCarthy saw ‘the marvellous photograph of Stephen, Wystan, Christoper I in the Observer? Do you think Shelley, Byron, Keats wd have looked like this?’ Then the coup de grace: ‘I’ve read this through, & it is an idiotic letter: Do forgive me: but I cannot write a new one: & I don’t deserve an answer. Still…’

Still, indeed. For nothing, not even David Caute’s damning, densely argued book, can take the shine off Berlin’s silky seductiveness. Having clapped Isaac & Isaiah shut thinking Berlin no more than a chancer on the make, you pick up one of the many volumes of Berlin’s essays that Henry Hardy has collected and edited (and that are being handsomely reissued in paperback by Princeton University Press) and are instantly won over again by his speed of thought and the immense web of philosophical connections he can spin across the centuries. True, Berlin never wrote as well as one suspects he spoke at all those dinner tables. His prose tended to windiness, and if you seek a way into his thought it is far better to start with the state-of-the-art summaries in Michael Ignatieff’s 1998 biography than with even the shortest essays in Hardy’s collection of Berlin’s greatest hits, The Proper Study of Mankind.

As for Deutscher, Caute acknowledges that far from destroying his career, Berlin’s Sussex subterfuges were likely for the best. The deadlines and pressures of journalism were far more suited to his personality, Caute believes, than the slow, even leaden pace of academic life, and the salary Sussex was offering wouldn’t have matched Deutscher’s (admittedly piecemeal) earnings from journalism and books. Nor were the majority of students of half a century ago any more inspiring than those of today. Deutscher should be in no doubt, counselled Sussex’s professor of history, Martin Wight, that the bulk of the written work he would have to mark would be ‘mediocre in quality, and a good deal of it… illegible’. Whatever Berlin’s intentions, in other words, they prompted one of those unintended consequences he was forever saying that history consisted in. If he’d really wanted to do Deutscher down, he’d have recommended him for the Sussex gig.

All of which means that Isaac & Isaiah is something of a mare’s nest. David Caute has written a fine and elegant book, but whether it’s a necessary one is rather more moot. Fascinating and colourful though it is, the story it wants to tell falls to pieces long before its end. And whatever wrongs Berlin did Deutscher, they hardly amounted to what Caute’s subtitle calls ‘the covert punishment of a Cold War heretic’. Little wonder the book lacks the drama of David Edmonds and John Eidinow’s account of the Wittgenstein / Popper spat about moral imperatives in Wittgenstein’s Poker. And whatever you think of Berlin’s machinations against what he saw as apologists for Leninism, they scarcely carry the historic import of the economic row that Nicholas Wapshott so precisely delineates in his recent Keynes Hayek: The Clash that Defined Modern Economics. If you didn’t know – or hadn’t guessed – that Isaiah Berlin was capable of bitching with the best of them, then Isaac & Isaiah may prove something of a slight eye-opener. But no real philosopher – even one as human, all too human as Isaiah Berlin – should let such a revelation dint another thinker’s reputation.

Christopher Bray is the author of 1965: The Year Modern Britain was Born, published by Simon & Schuster. (Buy this book from Amazon(UK).)

Isaac and Isaiah: The Covert Punishment of a Cold War Heretic, by David Caute, is published by Yale University Press. (Buy this book from Amazon(UK).)

Building: Letters 1960-1975, by Isaiah Berlin, is published by Chatto & Windus. (Buy this book from Amazon(UK).)

You’ve hit your monthly free article limit.

Support spiked and get unlimited access.

Support spiked and get unlimited access

spiked is funded by readers like you. Only 0.1% of regular readers currently support us. If just 1% did, we could grow our team and step up the fight for free speech and democracy.

Become a spiked supporter and enjoy unlimited, ad-free access, bonus content and exclusive events – while helping to keep independent journalism alive.

Monthly support makes the biggest difference. Thank you.

Comments

Want to join the conversation?

Only spiked supporters and patrons, who donate regularly to us, can comment on our articles.