Long-read

Incels: the ugly truth

The strange, self-loathing world of incels owes much to mainstream sexual confusion.

Want unlimited, ad-free access? Become a spiked supporter.

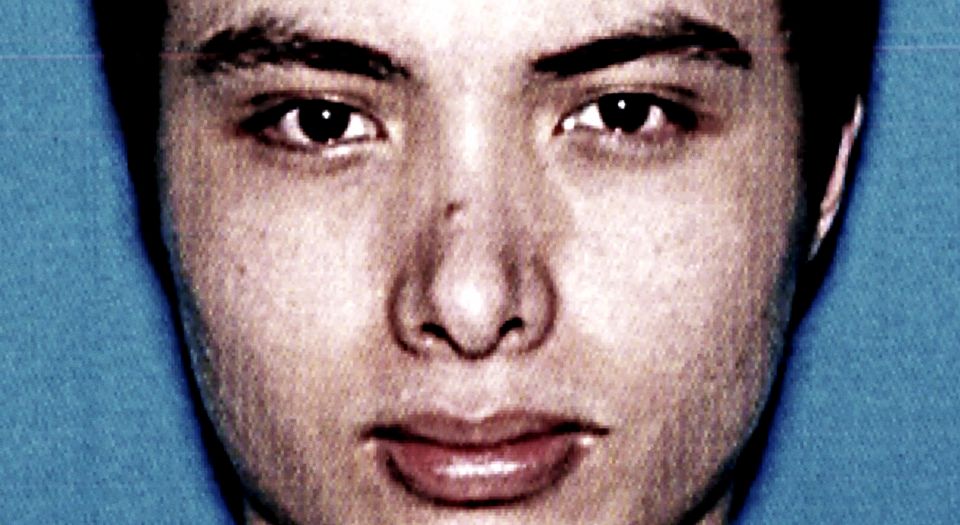

‘The Incel Rebellion has already begun’, wrote Alek Minassian, a self-described ‘incel’, in a Facebook post, minutes before he drove a rental van into pedestrians on a crowded street in Toronto in April, killing 10 and injuring 15. He was inspired by Elliot Rodger, whose shooting and knifing spree in Isla Vista, California killed six in 2014. Mass murders committed by incels have brought incel subculture to mainstream attention, but killers like Rodger and Minassian are a rare, extreme manifestation of the broader incel phenomenon.

Incels are ‘involuntary celibates’ – men frustrated with their inability to find a sexual partner. Estimates on the size of the incel community vary from thousands to hundreds of thousands. The forum ‘r/incels’ on Reddit had 41,000 members when it was banned in November 2017 for violating the site’s rules on violent content.

Incel forums, like the website incel.me and the message board /r9k/ on 4chan, are awash with anonymous declarations of self-pity, self-loathing and, at times, a violent misogyny directed at the women deemed responsible for their loneliness. Behind a great deal of mindless chatter and ‘shitposting’ is a shared understanding of how they came to be despised by the opposite sex, alongside a bewildering array of slang terms to describe and explain the various states of ‘inceldom’.

According to the incels, there is a ruthless sexual hierarchy, and as ‘beta males’, they find themselves at the bottom. The foil to the incel is a ‘Chad’ – a confident, attractive man with multiple sexual partners, comprising usually attractive but supposedly shallow women, known as ‘Stacys’. Chads are envied and despised in equal measure. Then there are the ‘normies’ (normal people), hated for their herd-like mentality and mocked for their ignorance of incel culture. ‘Blackpilling’ refers to the acceptance that the traits you are born with mean you are destined to be romantically unsuccessful. The term is a play on the moral dilemma presented by the 1999 film, The Matrix, in which Neo is offered a blue pill to remain in a world of illusion and a red pill to see the world as it truly is – ‘redpilling’ is a central trope in online men’s rights’ activism, while blackpilling is the incel equivalent. Physical traits such as height, facial features or penis size (sometimes posted with accompanying pictures), are said to play a big role in the incels’ low status, while a large number of them also blame self-diagnosed mental-health problems, particularly autism-spectrum disorders.

But while many incels are open about their flaws, ultimately the blame is laid on the women who overlook them. Women are seen as effectively slaves to their biology, guided by so-called ‘hypergamy’: an attraction to higher-status men linked to evolutionary psychology. Some parts of the so-called manosphere – a loose constellation of male-dominated online subcultures, including men’s rights activists and pick-up artists – believe that evolutionary psychology can be used to a man’s advantage, that certain techniques can be deployed to overcome a lack of attractiveness and confidence to manipulate women into bed or into a relationship. Incels reject even this bleak view and insist that beta males accept their place in the social-pecking order.

This belief in a rigid social hierarchy inevitably produces problems when it comes to race. ‘Ricecels’ (incels of Chinese and South East Asian origin) and ‘currycels’ (of South Asian descent) are often found posting photos of ‘proof’ of a theory called ‘JBW’, that in order for them to be successful with women they should ‘just be white’. Some white incels look upon black men with envy for their perceived sexual success, while a minority rail against any kind of ‘race mixing’ – even as a form of escape from inceldom.

In addition, incels speak of an ‘80:20 rule’ when it comes to sexual competition: the most attractive 20 per cent of men are said to be sought after by the most attractive 80 per cent of women, with the least attractive 80 per cent of men left to compete for the remaining 20 per cent of women. In previous eras, this situation would have supposedly been prevented by institutionalised monogamy. Some incels call explicitly for a return to a patriarchal society. Today’s world of relative sexual freedom, contraception, no-fault divorce and dating apps, on the other hand, is blamed for offering an abundance of opportunities for Chads and women, at the expense of incels.

Ultra-conservative calls for enforced monogamy may sound like they sit uneasily with a professed jealousy for the promiscuous lifestyle enjoyed by the Chads. But the incel relationship to sex is one of extreme ambivalence. A lack of sexual contact is seen, on the one hand, as the source of all life’s misery. On the other, it is central to the construction of incel identity. Forums are strictly policed in an attempt to root out ‘fakecels’ (fake incels), who are more sexually successful than they claim. ‘Bragging’ about relationships can lead to bans or having certain posting privileges revoked. This can be devastating to those who have invested such a great deal in this identity. Take 19-year-old Jack Peterson, one of the few incels to declare himself publicly to the media. Jack was banned from the forum incel.me after another user questioned his status as an incel, accusing him of bringing up a previous abusive relationship in order to brag about it. The Daily Beast reports that he spent three days straight (occasionally passing out) producing a 30-minute video and Powerpoint presentation that outlines in extensive detail why he believes he is sufficiently ugly and sufficiently mentally ill to still be considered an incel.

Angela Nagle argues in her book Kill All Normies that several of the bizarre online subcultures, from the manosphere to the alt-right, developed in tandem with, and are defined in opposition to, the extremities of the identitarian left. This is clearly the case with incels, where the currency found in unattractiveness on incel forums finds its parallel in the so-called ‘oppression olympics’ of identity politics, where a sense of identity and social status are tied inexorably to victimhood. In the incel world, many seem to revel in their repulsiveness – not only in their frequent use of foul language and imagery, but also in their choice of profile pictures. As most users post anonymously, their avatars might feature anything from other ugly men to frogs, aliens and Hitler.

When the media attempts to account for the incel phenomenon, they rely heavily on the trope of toxic masculinity. It is true that the incels exhibit a great sense of what might be called ‘male entitlement’, to women and to sex, and that they openly lament the passing of a male-dominated world. But far from upholding masculine values like stoicism and self-reliance, the incel subculture is imbued with today’s therapeutic sensibility. Far from being buttoned-up and unwilling to discuss their feelings like the masculine men of old, incels are spilling out their deepest, darkest thoughts and frustrations to strangers. Elliot Rodger spent 14 of his 22 years visiting multiple therapists and wrote a 114-page manifesto detailing his feelings of rejection before going on his killing spree. Plus, it is not only incels like Jack who talk up the poor state of their mental health online to gain the approval of their peers. Teenagers today regularly take to Twitter or Instagram to post about a litany of often self-diagnosed disorders.

Although the incels’ own explanations for their plight border on the absurd, can the emergence of incels be traced to real-world shifts? Research by the UCL Institute of Education suggests that one in eight 26-year-olds in Britain have yet to lose their virginity, up from one in 20 at the same age a generation ago. According to Ipsos MORI, 32 per cent of US millennials (born 1980-1995) are abstinent compared with 19 per cent of Generation X (born 1966-1979). What is more, its polling shows, paradoxically, that the proportion of millennials engaged in promiscuous sex is also higher than previous generations.

Concerned with this mismatch, economist Robin Hanson has proposed redistributing sex, just as the welfare state redistributes income. ‘Those with much less access to sex suffer to a similar degree as those with low income, and might similarly hope to gain from organising around this identity, to lobby for redistribution along this axis.’ Some denounced the idea as effectively a ‘right to rape’ or dismissed Hanson as creepy. Ross Douthat in the New York Times and Toby Young in the Spectator both say that we will have to redistribute sex eventually and that sex robots might offer a partial answer.

But clearly there have always been lonely, loveless men in society. What these debates miss is that the growth of the incel subculture is a product not just of young men not having sex, but of a society which has no agreed-upon cultural script when it comes to sex. The sexual revolution liberated a generation from religious attitudes and superstitious understandings of sex. But now that the sexual revolution is fading from view, there are few robust defenders of sex as a fun and guilt-free source of pleasure today. Ross Douthat writes that ‘culture’s dominant message about sex is essentially Hefnerian’ and promotes ‘frequency and variety in sexual experience’, but this misses key developments of recent years.

While it is unlikely that most ordinary people believe we live in a ‘rape culture’, this idea is nevertheless accepted and promoted by many educational institutions. In the UK, consent classes have been proposed not just for university students, but also school children and even MPs. While older millennials may have escaped them, their schooling still delivered grave warnings not only of unwanted pregnancies and STIs, but also of the emotional dangers of casual sex. The #MeToo movement has led to people being punished as sexual deviants for knee-touching and telling racy jokes. That is not to say that young people are now terrified of sex, or even that they buy into what they learn about sex from school or the media. Rather, it is that mainstream society offers no coherent or compelling understanding of sex and sexuality. Cultural norms are in flux and this produces a great deal of confusion. How else would 28 per cent of young women come to believe that winking ‘usually or always’ constitutes sexual harassment, compared with just six per cent of over-55s? How else can we account for the absurdity of mutually non-consensual sex? In the absence of a coherent mainstream, the incels’ bizarre world of Chads, Stacys, blackpilling and 80:20 rules seems to fill that void for some lonely young men. Just as many young feminists can relate their beliefs to the all-encompassing theory of rape culture, being ‘blackpilled’ provides a framework through which the incel can make sense of their place in a confusing sexual landscape.

Then there’s the question of masculinity. While it is overblown to say there is a ‘crisis of masculinity’ – talk of such a crisis has been ongoing since the mid-1980s – clearly this is another area where the modern world offers little more than confusion. For Jack Peterson, incel forums offer respite from society’s contradictory messages to ‘both “man up” and renounce your masculinity… it is like the one bright light you see is this community’. The explosion of popularity in clinical psychologist turned YouTube self-help guru Jordan Peterson (no relation to Jack) seems to confirm that the need to fill that void goes much deeper than the incels. His 12 Rules For Life is an international bestseller and he sells out arenas, preaching ‘masculine’ virtues. Peterson sets out to counter the ‘lack of an identifiable and compelling path forward’ for young people, particularly young men, who make up 90 per cent of his audience.

Overall, as strange, repulsive and extreme as the incel subculture appears, it is far from alien. Its absurd narrative of sexual politics is seized upon by misguided, alienated young men struggling to make sense of the adult world while the norms of masculinity and sexuality are in constant flux. Ironically, it channels a great deal of the excesses of the West’s therapeutic culture, identity politics and the fetishisation of victimhood – the very things that came to take the place of the old world that the incels claim to pine for.

Fraser Myers is a writer. Follow him on Twitter: @FraserMyers

You’ve hit your monthly free article limit.

Support spiked and get unlimited access.

Support spiked and get unlimited access

spiked is funded by readers like you. Only 0.1% of regular readers currently support us. If just 1% did, we could grow our team and step up the fight for free speech and democracy.

Become a spiked supporter and enjoy unlimited, ad-free access, bonus content and exclusive events – while helping to keep independent journalism alive.

Monthly support makes the biggest difference. Thank you.

Comments

Want to join the conversation?

Only spiked supporters and patrons, who donate regularly to us, can comment on our articles.