HyperNormalisation: good ideas, bad narrative

Adam Curtis's latest just doesn't hang together.

Want unlimited, ad-free access? Become a spiked supporter.

While watching the trailer for Adam Curtis’s latest documentary, HyperNormalisation, I had a sinking feeling. The endorsement from Russell Brand had already put my guard up, but it was the opening text that did it. While a woman sings Emmylou Harris’s ‘Till I Gain Control Again’, words in capitals read: ‘We live in a world where the powerful deceive us. We know they lie, they know we know, they don’t care. We say we care, but we do nothing. And nothing ever changes. It’s normal. Welcome to post-truth politics.’

Declaring that we live in a world of post-truth politics is a clever reworking of that well-loved phrase among conspiracy theorists: ‘Wake up, sheeple!’ In fairness to Curtis, patronising conspiracy theories are not what HyperNormalisation is about. But it’s hard to know what the 166-minute documentary actually is about. Curtis’s documentaries have always been like collages of thoughts, strung together by his pondering voice. But HyperNormalisation is a step too far into the abstract. Jumping from the financial crisis in 1970s New York to clips of young girls dancing on webcam in the 2000s, from footage of the Lockerbie bombing to a weird interlude looking at internet usage in the early 1990s, it feels more like a late-night musing than a coherent documentary.

HyperNormalisation attempts to look at the breakdown of realpolitik after the Cold War, and the shift away from big ideas and towards managerial politics. Curtis tells us that, from the late 1960s onwards, lefties and establishment politicians alike sought not to change the world, but to manage present conditions in order to achieve as agreeable a future as possible. Low horizons indeed. Curtis begins in 1975 New York where, in a state of financial ruin, the city was forced to hand over financial control to the banks. From there, Curtis takes us to Syria, where he begins to tell the story of the unravelling of the Middle East. We are shown footage of the breakdown of the Soviet Union, the emergence of suicide bombers in Syria and the warmongering and game-playing of Western interventionists. Alongside this, using clips of the Occupy movement and the Arab Spring, Curtis looks at why popular left-wing movements failed to stop the collapse of capital-p politics.

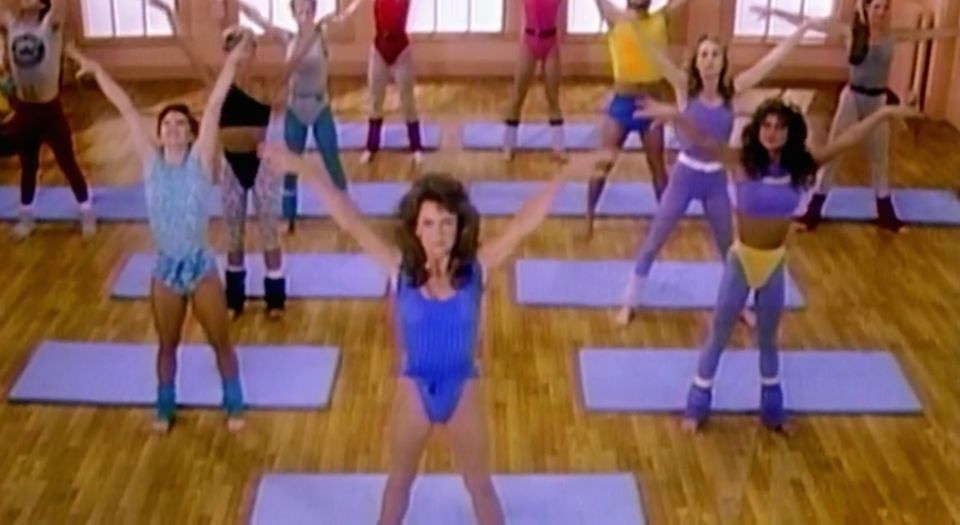

It’s a lot of history to get through in just under three hours. It feels like Curtis is trying to cover too much ground. And, in the process, he misses out some crucial points. Curtis explains how, after the bankers took control in New York, the city’s remaining middle-class radicals decided to take a step back. He uses fantastic footage of the rock star Patti Smith, heroine of bullshit leftism, exclaiming her delight at seeing New Yorkers watching films in movie theatres ‘over and over, all day because they don’t have enough dough but it’s some entertainment, you know’. This is pretty much the only semi-critique we get of 1970s lefties’ inability to mount a proper, progressive response to the banking crisis. Instead, Curtis shows us a clip of a Jane Fonda workout video, with the subtitle ‘Jane Fonda gave up on socialism and started another revolution’. We’re told that, instead of changing the world, Fonda, and the idiots who followed her, decided to focus on what they could safely control – their appearance.

For the most part, the documentary is a narrated history of recent conflicts in the Middle East. Curtis looks at how semi-secret relationships between Western politicians and Middle East dictators fuelled the collapse of Syria, Libya and Iraq. There is fascinating footage of Muammar Gaddafi as a young, handsome man, waxing lyrical about his ‘third universal theory’, as well as horrific scenes from the Sabra and Shatila massacre. Some of it is hard to watch. Where news reports often turn away from the carnage, Curtis insists that we stick with it. He uses bystander footage of bombs being dropped inches from the cameramen, and bodies being carried away by blood-stained civilians.

But what is it that Curtis is asking us to consider? The underlying sense throughout the documentary is that he is attempting to open our eyes. We’re shown women in salons in the Soviet Union, teenagers video blogging about their lives, all interspersed with footage of Vladimir Putin looking like a cartoon villain and Tony Blair sweatily apologising for Iraq. It’s as if he’s saying: ‘Hey, idiots, don’t you see? They’re all conspiring against you, and all you want to do is talk about your hair.’

The problem is that Curtis tells us nothing we didn’t already know. Yes, US presidents and Middle East dictators have played secret games for years. Yes, politicians lie and scheme. But rather than looking at why such behaviour continues to define international politics, Curtis seems satisfied with simply pointing out that we’re all doing nothing while the world goes to hell in a handcart.

Curtis is right to draw attention to the death of big political ideas, but he fails to look at what has taken their place. The Occupy movement, which he briefly looks at, would have been a perfect place to explore the trend towards personalising politics, where what you feel is more important that what you think. Similarly, when his attention turns to Donald Trump, who he describes as someone akin to a suicide bomber, Curtis fails to put his finger on what is really behind Trump’s popularity – that is, the rise of populism, and the break with the establishment. There are moments of brilliant insight, but they are never developed.

HyperNormalisation left me with more questions than answers, which is often a sign of a successful documentary. Unfortunately, in this case, it was more confused than it was curious. And, at times, Curtis gets things really quite wrong. His brief mention of the Brexit vote was discussed alongside footage of Sissy Spacek covered in blood in Carrie – a crass, low dig at Leave voters. Doesn’t Curtis realise that the Brexit vote was anything but ‘post-truth politics’? Brexit was an expression of a desire for real politics, and democracy – the most powerful political idea of all. Curtis sets out to tell the ‘hypernormalised’ plebs how it really is. But this pleb’s not convinced.

Ella Whelan is assistant editor at spiked. Follow her on Twitter: @Ella_M_Whelan

£1 a month for 3 months

You’ve hit your monthly free article limit.

Support spiked and get unlimited access.

Support spiked – £1 a month for 3 months

spiked is funded by readers like you. Only 0.1% of regular readers currently support us. If just 1% did, we could grow our team and step up the fight for free speech and democracy.

Become a spiked supporter and enjoy unlimited, ad-free access, bonus content and exclusive events – while helping to keep independent journalism alive.

———————————————————————————————————————————–

Exclusive January offer: join today for £1 a month for 3 months. Then £5 a month, cancel anytime.

———————————————————————————————————————————–

Monthly support makes the biggest difference. Thank you.

Comments

Want to join the conversation?

Only spiked supporters and patrons, who donate regularly to us, can comment on our articles.