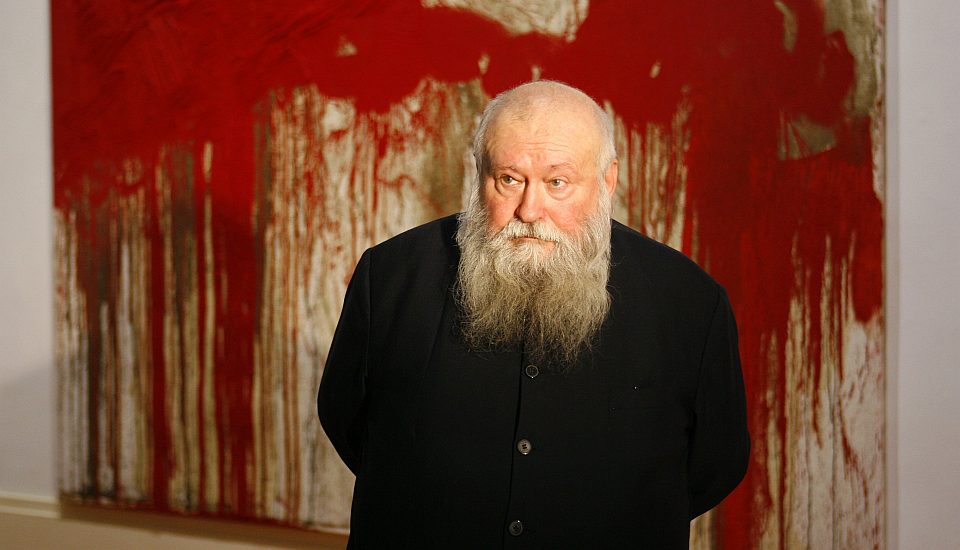

Hermann Nitsch: Blood on the museum floor

A Mexican art gallery has turned the pretentious Austrian into a free-speech martyr.

Want to read spiked ad-free? Become a spiked supporter.

Another example of censorship through petition power has come to light this month. An exhibition by Actionist Austrian artist Hermann Nitsch was scheduled to take place in February at Fundación Jumex, Ecatepec de Morelos, on the outskirts of Mexico City. But on 31 January it was cancelled. This followed an online petition against the Nitsch display, though, in its announcement, Jumex does not link the petition to the cancellation. The Nitsch exhibition has been replaced by a group exhibition of works by other artists in the Jumex collection – a mix of contemporary and modern art, including works by the usual names familiar from the network of state-supported museums, private foundations and international galleries, including Cy Twombly, Martin Creed and Lawrence Wiener.

Seventy-six-year-old Nitsch is considered a serious artist, with works in many museum collections worldwide, including the Tate Gallery, MoMA and Centre Pompidou, and who has exhibited frequently over a 50-year career. He came to prominence as part of the Viennese Actionist School that emerged in the 1960s, which is characterised by performances involving violence and humiliation. He is most notorious for his theatrical presentations which combine live action, nudity, bloodletting, blood drinking and degradation as spectacle. In the past, he has used live animal sacrifice as part of performances. It is unclear what the proposed Nitsch exhibition at Jumex was to consist of, but it seems it would not have included any animal sacrifice. He apparently ceased using killing in performances almost 20 years ago. It may be that protesters did not know this, or perhaps they simply wanted to express general disapproval of Nitsch’s past perfomances. Either way, it seems clear no animal deaths would have resulted from the proposed Jumex exhibition.

Nitsch’s New York gallerist Marc J Straus has pointed out that Jumex owns and displays work by Damien Hirst which features animals preserved in glass tanks of formaldehyde solution.

Nitsch has positioned himself as a figure who challenges social constraints through shocking the viewer, much in the same way Antonin Artaud’s Theatre of Cruelty did in the 1920s and 1930s. He has written of himself: ‘[T]hrough a simple and uncomplicated application of critical epistemology I can recognise and say that solely I exist unconditionally.’ He acts as a pseudo-priest enacting cathartic rituals, explicitly portraying art today as a substitute religion and implicating the audience through their voluntary spectatorship of degrading performances.

As Brendan O’Neill pointed out last year, censorship of unpopular speech is often the domain of online activism rather than down to state officials or private organisations. Such diffusion of criticism means that no one person or organisation is ultimately responsible for censorship, making it hard to combat such attacks. Opposition to an event or publication which can be portrayed as ‘widespread’ or ‘an outcry’ can be a convenient excuse for nervous institutions to ditch projects that they no longer have the courage to support, even when the opposition is vocal but not large and no legal issues prevent the event from going ahead.

Out of all contemporary art, Nitsch’s sacrificial performances are the hardest to argue in favour of as a matter of free speech because they raise serious ethical considerations. However, rather than simply boycott the presentation, objectors have prevented others from seeing and considering Nitsch’s art. The suppression of Nitsch is likely to turn him into a minor martyr of moral opprobrium, and an icon of censored free speech, whereas if the exhibition had gone ahead he might simply have been considered – as he is by some in the art world – as a charlatan peddling distasteful spectacles and an egotist attempting to take on the mantle of a modern shaman. If the exhibition had proceeded and Nitsch’s art had been seen in all its pretentious asininity by a handful of bemused and irritated viewers, those who disapprove of Nitsch’s art would have allowed the artist to condemn himself. Those critics and artists who dislike Nitsch’s work and are inclined to condemn it are now – however reluctantly – inclined to support his case.

Nitsch’s art is generally ill-judged, often pretentious and (formerly) sometimes cruel. In having to defend it against a censorious clique, the critic in favour of free speech finds himself defending a fool against a group of well-meaning but thoughtless people who adhere to the dangerous principle of ‘thou shalt not offend’, when both this artist and his opponents deserve to languish in obscurity.

Alexander Adams is a writer and art critic. He writes for Apollo, the Art Newspaper and the Jackdaw. His book The Crows of Berlin is published by Pig Ear Press. (Order this book from Pig Ear Press bookshop.)

Who funds spiked? You do

We are funded by you. And in this era of cancel culture and advertiser boycotts, we rely on your donations more than ever. Seventy per cent of our revenue comes from our readers’ donations – the vast majority giving just £5 per month. If you make a regular donation – of £5 a month or £50 a year – you can become a and enjoy:

–Ad-free reading

–Exclusive events

–Access to our comments section

It’s the best way to keep spiked going – and growing. Thank you!

Comments

Want to join the conversation?

Only spiked supporters and patrons, who donate regularly to us, can comment on our articles.