Long-read

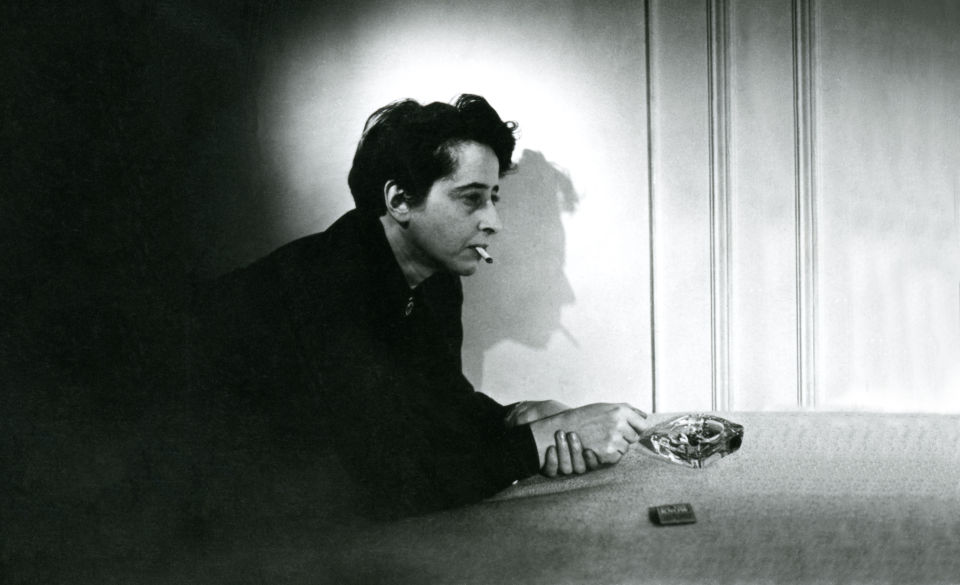

Hannah Arendt: the power of thinking

A new documentary reveals a thinker always willing to challenge orthodoxies.

Want unlimited, ad-free access? Become a spiked supporter.

In Vita Activa: The Spirit of Hannah Arendt writer and director Ada Ushpiz weaves an incredibly rich tapestry from the life and work of this quintessential public philosopher. Vita Activa consolidates Arendt’s place in the pantheon of eminent 20th-century philosophers, and captures a visionary who addressed humanity’s most profound and perennial moral questions. Indeed, one cannot fail to recognise the enduring relevance of her contributions, especially in light of Europe’s migrant crisis and the barbarism of Islamic State.

Arendt’s existential experience of being a Jewish exile, having fled her native Germany in 1933 for the relative safety of Paris, was crucial to the development of her thinking. In Vita Activa, philosopher Judith Butler describes Arendt’s ‘exilic perspective’ as ‘both Jewish and non-Jewish’. It also positioned her forever outside the home, outside the masses, outside the collective. Classic political ideologies offered her no refuge. This was her choice. Much of her writing is imbued with a dread of ideology. She eludes categorisation. She is not a classic liberal or a revolutionary Marxist. Her vantage point is unique.

In The Origins of Totalitarianism, Arendt highlighted the plight of displaced First World War migrants who remained homeless, stateless and enjoyed no rights. She lamented how Jews, Trotskyists and the like became the unwanted of Europe. Eventually, official SS propaganda expressly stated that, ‘if the world is not yet convinced that these Jews are the scum of the earth, then it soon will be when these beggars without money or passports cross over their borders’. Ushpiz suggestively juxtaposes these unwanted alongside today’s migrants who, likewise, enjoy limited, tentative hospitality in Europe and America.

The displacement and political homelessness of Jews made Arendt very sympathetic to the Zionist movement in the 1930s. But by the 1940s, she shifted position. In Zionism Reconsidered (1944), Arendt expressed dismay at the success of the revisionist Zionist programme, which insisted on Jewish sovereignty over the whole territory of Eretz Yisrael (which encompassed Mandatory Palestine). ‘This time’, Arendt lamented, ‘the Arabs were simply not mentioned in the solution’. This left them the choice either of being second-class citizens at home or of having to accept voluntary emigration. ‘A Jewish home that is not recognised and not respected by its neighbouring people’, she prophesied, ‘is not a home but an illusion, until it becomes a battlefield’. Arendt saw how Zionism’s once inspirational, revolutionary and progressive ideals had fallen under the spell of ‘dialectical necessity’ to the extent that its followers were willing to adapt to almost any inhuman conditions. Consequently the socialist, revolutionary Jewish national movement had been transformed into a nationalistic chauvinism directed against neighbours and potential allies.

For Arendt, totalitarian ideology succeeds precisely because it destroys the process of thinking. Thinking is not the preserve of the elite few. Every human being is a thinking creature possessing a potential for reflection and independent judgement. If Vita Activa proves anything, it is that Arendt was the living embodiment of her belief that to think always means to think critically. Thought undermines rigid rules and generalisations. Everything that happens in thinking can be scrutinised. Thus, there are no dangerous thoughts, since all dangerous ideas can be undermined by new thinking. Non-thinking, by contrast, poses the real danger.

If her critique of the Zionist movement’s chauvinism scandalised some Jews, it was as nothing compared to Eichmann in Jerusalem (1963), in which she refused to gloss the complexities of the Holocaust, and implicated the Jewish leadership. The whole truth, she remarked, was that the Jewish councils (Judenräte) had cooperated in one way or another with the Nazis. They were like captains of a sinking ship who, in order to limit the death toll, cast overboard a great part of their precious cargo in order to bring the ship safe to port. The role of the Judenräte in the destruction of their own people was, for Arendt, undoubtedly the darkest chapter in the whole dark story.

Despite the fact that this was a relatively small part of Eichmann in Jerusalem, critics accused her of being a ‘self-hating Jew’, and she was excommunicated from the Jewish communities in America, Europe and Israel. In Eichmann in Jerusalem Arendt revealed herself to be an independent, anti-mythological thinker. She thought Nazism had been an organised attempt to eradicate the reality of the unique human being, and refused to accept the cliche of Eichmann as a Satanic, sadistic monster.

Responding to Eichmann’s trial, Arendt was forced to reflect on her own thoughts about the totalitarian system. It was always the system, rather than individuals, she referred to. Now she felt compelled to ask: who was Eichmann? She concluded that he was an individual with free will, who had become a functionary cog in the machine of terror. Her ideas threatened national myths. The Eichmann trial, in her estimation, was a show trial involving bad history and cheap rhetoric. Eichmann had become a proxy for anti-Semitism throughout history. To view Eichmann’s crime primarily as a crime against Jews as such was not false so much as trivial. The supreme crime with which the court was confronted was a crime against humanity. After reading the 3,600-page transcript of Eichmann’s police hearing, Arendy decided he was intelligent, obtusely shallow, but not demonic. The banality of evil is to be found precisely in this shallowness, this superficial acceptance of clichés and conventional wisdom. We resist evil, she claimed, by resisting the seductive force of surface appearances and conventional things. In a letter to her mentor and friend Karl Jaspers, Arendt once said: ‘Any oversimplification, whether it is that of the Zionists, the assimilationists, or the anti-Semites, only serves to obscure the true problem.’

After the full horrors of the Holocaust came to light, the most perplexing question was how normal men, affected by the sight of suffering, were nevertheless able to become brutal killers. Arendt thought that the trick involved redirecting natural instincts of pity towards the self. So, instead of saying, ‘What horrible things I did to people!’, the murderers would say, ‘What horrible things I had to watch and do’. Eichmann himself said that seeing snipers killing Jewish women and children ‘was horrible for me. I was not strong enough to sustain… [and could not] remain indifferent to a sight like that.’ Arendt concluded that Eichmann was a functionary with pangs of conscience, but who had nevertheless remained a functionary and therein became a dangerous man.

Arendt maintained that history’s worst crimes have been committed in the name of some kind of necessity. Vita Activa illustrates this with Goering’s testimony on Nazi policy at the Nuremberg Trials. There were certainly brutalities, Goering argued, ‘but given the size of the enterprise, the German freedom revolution was the most bloodless and disciplined of all of history’s revolutions’. Underlying such ruthless power politics is an entirely new and deceptive concept of reality. Arendt had perceived something like this thought-suspending banality of evil a few years prior in philosopher Martin Heidegger’s famous 1933 Rektoratsrede at the University of Freiburg. His idea of ‘German reality’ abolished individuals in one common ideal. Arendt noted that within her intellectual milieu, the grand ideals of National Socialism had become an unspoken rule. There was no critical dissent.

But just as she had with Eichmann, Arendt resisted the temptation to condemn Heidegger as an ‘evil man’, or even as an anti-Semite. Rather, Heidegger was one who, when the chips were down, refused to allow his thinking to become a real judgement in the world of lived experience. The man who had waxed eloquent on ‘phenomenology’ refused to apply it in his own life. He didn’t say, “No! I will not do that!”.

Like Heidegger, who had been Arendt’s lover as well as her teacher, Eichmann had had a Jewish mistress. He didn’t hate Jews. Rather, Eichmann was a self-described idealist; someone who believes in his idea and lives for it in a way that shields him from reality. Arendt’s notes reveal that she unequivocally thought evil was closely entwined with idealism. In saying that evil is ‘banal’, she did not mean that there was nothing horrific in Nazi crimes. She meant that when ideology eradicates thinking and becomes reality, the most deplorable acts appear as normal to the perpetrator. By contrast, thinking is when you inhabit an alienated space apart from the norm. The thinker is distinguished by her ability to experience dissonance amid the ‘common sense’ of the collective. This was what Eichmann did not do. He was fully ‘at home’ in the Nazi milieu, which had become so ‘ordinary’ that he didn’t experience dissonance between his actions and the norm. ‘Evil is not only conscientious’, Arendt observed, ‘but also sentimental’. Eichmann had no criminal motives; he wanted to cooperate. He wanted to say ‘we’. Arendt’s insight was that this cooperation, this wish to say ‘we’, was enough to enable these horrific crimes. She recognised that evil’s penetration into the real world does not announce itself with fire and brimstone. Rather, it appears with the banality of ‘common sense’ and the apparent necessity of ‘doing one’s duty’.

To understand what it means to fall prey to ‘idealism’, we must understand that the sympathetic left-wing Guardian reader is every bit as susceptible to this sentimentality and conscientiousness, this giddy intoxication, as any right-wing nationalist. It is precisely because we can be so enthralled with sanctimonious participation in the obviously ‘good’ ideology, that we cease to think. And this is a danger that can be exploited. If you want the mass of well-meaning lefty liberals to believe that the moon is made of cheese, just use a political tool like Donald Trump. Once he declares that the moon is certainly not made of cheese, even the most rational among us might begin to wonder whether it is. Political propaganda works because it short-circuits thinking, and replaces it with demonisation and platitudes. We have as much to fear from how anti-Trumpism is used as an instrument of mass manipulation as we do from Trump himself. Even suggesting this becomes risky in an atmosphere where anti-Trumpism has become an ideological orthodoxy and a substitute for deep reflection on a complex set of new political circumstances. Even the best and brightest among us can be prevented from experiencing cognitive dissonance when we are swept up in the collective ‘common sense’ of our milieu.

In Vita Activa, Judith Butler expresses unambiguous support for ‘plurality’. Even she, in presenting her positive assessment of Arendt’s insistence on plurality, falls prey to the common-sense view that seems so rational and so logical, that doubting it becomes a kind of thought crime. She, too, seems to have ceased to question whether pluralism per se is always and everywhere a good thing. Even with all the good intentions in the world, indiscriminate openness to the ‘other’ can take the form of moral relativism – a refusal to judge – that can easily be exploited and abused in ways that we did not foresee. Our choices would then be narrowed to a terrible dilemma between collaboration with powerful persecutors or dissent and victimisation by them. A radio interviewer asked Arendt to respond to exactly this age-old Socratic dilemma: whether it is better to suffer evil or to inflict it. Arendt responded that Socrates had maintained that there was no proof that a man must conduct himself one way or the other. Rather, there is an existential commitment to be made, and the decision one way or the other, says Arendt, is based on how we choose to live with ourselves. One man says to himself, ‘I don’t want to do this because I don’t want to live with someone who would’. Living with oneself means having this inner dialectic, which is the basis of thought – a form of thought of which any adult human being is capable, regardless of academic training.

It is tempting to imagine oneself treading in the footsteps of Arendt by reductively transposing the situations described in Vita Activa to present-day Europe. After all, part of Arendt’s genius was to perceive important ideological similarities between discrete historical events. We would be foolish not to seek to apply lessons learned from the past. But, while it might be gratifying to use Vita Activa to draw parallels between the post-First World War migrant situation and the current crisis, or between past and current right-wing nationalism, to fall prey to unreflective, facile assumptions would be a travesty of the spirit of Hannah Arendt.

Terri Murray is director of studies at Hampstead College of Fine Arts & Humanities, London. She is the author of Thinking Straight About Being Gay: Why it Matters if We’re Born That Way (2015). (Buy this book from Amazon(UK).)

Vita Activa: The Spirit of Hannah Arendt is available from www.go2films.com. Watch the trailer here:

Picture by: Zeitgeist films.

£1 a month for 3 months

You’ve hit your monthly free article limit.

Support spiked and get unlimited access.

Support spiked – £1 a month for 3 months

spiked is funded by readers like you. Only 0.1% of regular readers currently support us. If just 1% did, we could grow our team and step up the fight for free speech and democracy.

Become a spiked supporter and enjoy unlimited, ad-free access, bonus content and exclusive events – while helping to keep independent journalism alive.

———————————————————————————————————————————–

Exclusive January offer: join today for £1 a month for 3 months. Then £5 a month, cancel anytime.

———————————————————————————————————————————–

Monthly support makes the biggest difference. Thank you.

Comments

Want to join the conversation?

Only spiked supporters and patrons, who donate regularly to us, can comment on our articles.