Hack Attack: how Nick Davies saved the world

…by helping to close the News of the World.

Want unlimited, ad-free access? Become a spiked supporter.

Hack Attack, Guardian writer Nick Davies’ exhaustive treatment of how he exposed the phone-hacking scandal at the News of the World, leaves one question unanswered. If this really is the ‘definitive, inside story of one of the major scandals of our age’, which George Clooney believes deserves the Hollywood treatment, then how come it is so definitively dull?

The blurb for Davies’ book calls it a ‘nail-biting account of an investigative journalist’s quest’. You would have to be of a peculiarly nervous disposition to bite your nails through these 400-odd pages. Especially as the subtle subtitle – ‘How the Truth Caught up with Rupert Murdoch’ – rather gives away whodunit (at least in the author’s eyes) on the book’s front cover.

Perhaps part of what makes Hack Attack hard to chew through and swallow is the ‘forensic’ treatment for which others have praised Davies. It’s a blow-by-blow, email-by-email, anonymous allegation by anonymous allegation trawl through the history of the hacking affair, beginning with ‘Chapter 1: February 2008 to July 2009’, and climaxing with ‘Chapter 14: 28 June 2011 to 19 July 2011’. The effect is not unlike listening to a policeman in the witness box, reading verbatim from his notebook in a uniform drone of voice for hours on end.

That might seem appropriate. After all, to judge by the account he gives here, Davies’ chief role throughout the phone-hacking investigation was effectively to act as the Provisional Wing of the Metropolitan Police, urging them to crack down harder on the Murdoch papers and informing the Met that a stricter interpretation of the Regulation of Investigatory Powers Act (RIPA) would enable them to arrest more members of the press. Which seems a novel interpretation of the journalist’s role of ‘speaking truth to power’. In the end, of course, the Met pursued the lead offered by detective Davies, launching the biggest criminal investigation in British police history against tabloid journalists.

A bigger reason why Hack Attack falls so short of its own billing is that, whisper it, phone-hacking at the News of the World, which ended in 2006, really isn’t ‘one of the major scandals of our age’. Getting a dodgy private detective to listen to the voicemail messages of celebrities was low as well as illegal. Doing the same to the voicemails of crime victims such as murdered teenager Milly Dowler, or the parents of abducted toddler Madeleine McCann, was indefensible. Yet in the historic scales of scandal and crime involving the abuse of power (which is what Davies claims to be concerned with), these are hardly the weightiest of matters.

Far more dangerous, as spiked has argued from the start, has been the way that the phone-hacking scandal became the pretext for powerful forces to launch a wider war against the vital liberty of press freedom, seeking further to constrain and sanitise the unruly British tabloid press. Davies appears blind to this danger – indeed, he is a fan of such powerful sanitisers as Lord Justice Leveson – obsessed as the Guardian man is with his own anti-Murdoch ‘quest’.

Davies begins the book describing how ‘a small group of us’ – but mainly him, we are to understand, backed by his close pal Alan Rusbridger, the Guardian editor – got into ‘a fight with the press and the police and the government, all of them linked to an organisation which had been created by one man’. Who could he possibly mean? For Davies, Rupert Murdoch is not just one of the most powerful people on Earth, but ‘you could argue that he is, in fact, the most powerful’. You could, yes, in the same way ‘you could argue that’ listening to some voicemail messages is a major crime against humanity.

From there onwards, Hack Attack is shot full of over-familiar fantasies about the hidden hand of Murdoch pulling all the strings, fixing all the elections and more or less hacking all the phones, manipulating everything through ‘the secret world of the power elite’. Hack Attack is another volume to take its place on the groaning bookshelf we might label ‘Murdochmania’, alongside such bonkers tomes as Dial M for Murdoch by Labour MP Tom Watson, a key contact of Davies.

No doubt the fact that I have taken the Murdoch shilling by writing for The Times, The Sunday Times and more recently the ‘evil’ Sun means that nothing I say here can be trusted, of course. Murdoch does not need an old leftie like me – who was on the other side during the Wapping dispute of the 1980s – to defend him. We do, however, need to counter the burgeoning conspiratorial claptrap that seeks to reduce the problems of contemporary capitalism –and explain away the failures of its critics – with reference to a secret system ‘created by one man’. As some of us have often observed, if Rupert Murdoch did not exist, these people would have to invent him to give themselves a scapegoat.

Scratch the surface, anyway, and it becomes clear that the ‘one man’ whom Hack Attack is most obsessed with is not so much Murdoch as the author himself. This is the moral Parable of Davies and Goliath.

Playing psychologist, Davies claims that all reporters are driven by ‘some kind of deep need’. His, apparently, is a ‘deep-seated urge’ to combat bullies. This urge, he reveals, now laying down on the therapist’s couch for our edification, stems from having ‘spent my childhood being hit by people’. (He revealed in a recent interview that he had also been bullied at his posh private school for being a member of a minority group – the only Guardian reader in the class.) This, he apparently realised retrospectively, explained why ‘over and again I have been drawn to stories where I might have saved victims’.

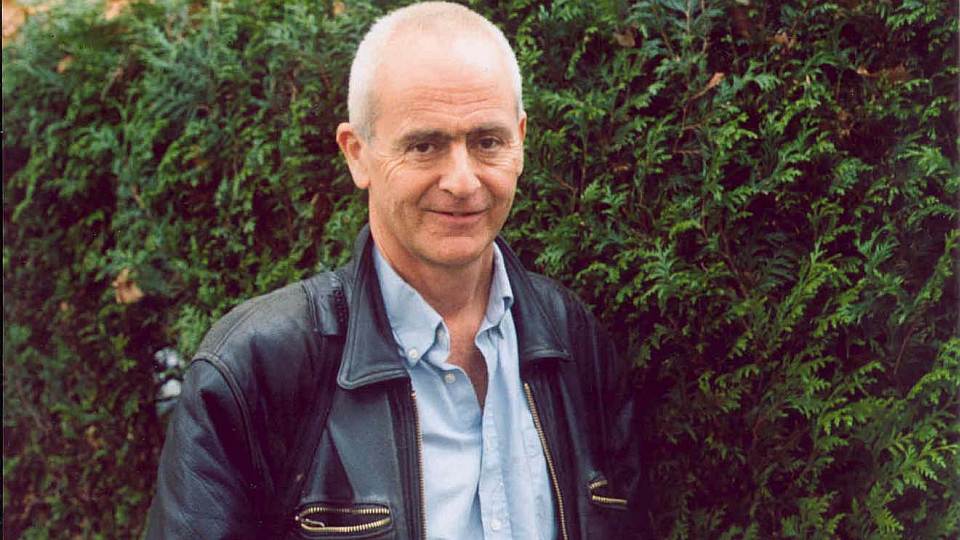

By his own admission, then, Nick Davies is no mere reporter. He is a crusader on a quest, clad not in cape and bat mask but in his ubiquitous ‘cool’ leather jacket (here is the news, Nick: you are in your sixties now). Davies’ self-aggrandising self-image as a crusader on the side of Good was confirmed in that interview with the Press Gazette, where he announced with all due modesty that ‘the Bad Guys hate me…and would like to do my legs’. Just in case there is any confusion here, the dark forces he is talking about are other journalists, rather than gangsters or jihadists.

The trouble with being righteous is that you start thinking you can do no wrong. That helps to explain why, in pursuit of its zealous crusade against phone-hacking tabloid hacks, the high-minded Guardian overstepped the mark and rushed to broadcast gossip and rumour as fact in a way that would have caused outrage had it been the News of the World.

By the start of 2012, the Guardian had published no fewer than 40 corrections, apologies and withdrawals in relation to stories it had run about the Murdoch press and phone-hacking. Its most dramatic mistake turned out to be the story that made phone-hacking a national political issue, and in the process made Nick Davies a media star: his Milly Dowler ‘false hope’ report.

On 5 July 2011, in a frontpage exclusive by Davies, the Guardian reported that the News of the World had not only hacked the voicemail of the abducted Surrey schoolgirl in 2002, but had also deleted some messages, giving the Dowlers false hope that their daughter was alive. As Hack Attack puts it, when that story was published, ‘There was a white flash and a mighty explosion’. The phone-hacking scandal, long of interest largely to the Guardian’s editorial conference and offended celebrities, suddenly exploded across public and political life. Within days Rupert Murdoch had announced the closure of the News of the World, and Tory prime minister David Cameron had announced the Leveson Inquiry to find a new way of policing the British press.

Before too long, however, it became clear that the story was not quite the clear ‘white flash’ of light that Davies had suggested. The NotW had certainly hacked Milly Dowler’s mobile phone, but there was no evidence that it had deleted any messages or given her parents false hope. Not for the first or last time, the zealous crusader had been too quick to draw his sword and smite the heathens. Some have even suggested that, to coin a phrase, the truth had ‘caught up with Nick Davies’. He is having none of that, however, announcing in Hack Attack only that ‘the picture was blurred’.

Funny that; it had seemed pretty clear in his one-eyed view when he wrote that explosive article about the News of the World, published under the subheading: ‘Exclusive: Paper deleted missing schoolgirl’s voicemails, giving the family false hope.’ Of course, anybody can make a mistake on the basis of what he thought were reliable (police) sources at the time. But a self-righteous crusader can never admit that he was in the wrong, only that the picture has become ‘blurred’, like a spiritual vision.

So, what about the closure of the News of the World that followed his explosive but inaccurate Milly Dowler story? That cost some 200 journalists their jobs. Might that have something to do with the Bad Guys’ hostility towards Davies? Not a bit of it. In Hack Attack he seems keen to distance himself from the impact of his most famous exclusive. He unearths some obscure emails from News Corp suits, apparently as proof that the closure could not have been a consequence of his story since, he now claims, the company was plotting to shut down the NotW anyway. Honest guv’nor, it wasn’t me, I wasn’t even there, a big boy done it and run away, etc.

Funny that; Davies did not seem quite so shy about taking the credit in 2012, when he was announced as the winner of the prestigious Paul Foot Award for investigative journalism. According to the glowing report of his triumph in the Guardian, ‘The organising committee, in its citation, praised Davies’ “dogged and lonely reporting”, the impact of which forced “a humbled Rupert Murdoch to close the News of the World”’. That a serious journalist could win a top investigative reporting award for helping to close down Britain’s bestselling newspaper was a sign of the dire state of the debate about press freedom in the UK. No news yet of Davies having returned that award as he seeks to wriggle off the hook.

And what of the Leveson showtrial of the tabloid press and the police campaign against tabloid journalists that also followed his phone-hacking crusade and Milly Dowler mistake? Hack Attack expresses no sympathy for the 63 hacks rounded up by the Metropolitan Police, often in dawn raids on their homes, and left in limbo on police bail. As for the Leveson inquisition – not into hacking but the entire ‘culture, ethics and practices’ of the UK press – Davies thinks it was ‘wonderful’, revelling in how the good lord justice lectured the supposedly free press about how they should behave, like ‘a headmaster addressing the morning assembly’. Jolly good show!

Not only was Davies a Leveson luvvie, he has since looked like a Hugh Grant groupie, becoming one of a handful of journalists to sign the Hacked Off statement demanding that the press must bend the knee to the politicians’ system of state-backed regulation via the Royal Charter. His attitude earned him the label of ‘traitor’ from Andy Coulson, the former News of the World editor and Tory spindoctor jailed for his part in phone-hacking. Given the source, Davies may well wear that one with pride. Others may think that, on this at least, Coulson had a point.

But perhaps we should be more generous to Davies the redoubtable investigator, and not question his personal motives. Instead, let’s just agree that, whatever he thought he was doing, in practice he has acted as a useful idiot for the enemies of press freedom. He has helped to provide a cloak of moral legitimacy behind which those who fear and loath the popular press and the populace have been able to pursue their dream of taming and sanitising insolent journalism.

For all their supposedly clear-eyed take on ‘truth and power’, the likes of Davies and Rusbridger can appear remarkably naive, particularly when it comes to state power. At the end of Hack Attack, Davies laments that, despite all their efforts, ‘very little has changed’, basically because Rupert Murdoch is still rich and owns newspapers. The reality is that a great deal has changed on the battleground of the free press wars since the hacking scandal began, almost all of it for the worse.

Just last week we learned how the RIPA that Davies encouraged the Met to use against the press over phone-hacking has been deployed to spy on Sun journalists and hunt down their confidential sources. Rusbridger has finally stirred himself to protest against this state attack on the press. Which might be more convincing if the Guardian chief – a rare editor, according to Davies, with ‘a backbone’ – had stood up against such intrusion during the Leveson circus, instead of bending his backbone on to a music stool and writing a book about learning to play the piano while press freedom was burning.

Clooney may have some trouble turning this tome into a Hollywood thriller, especially as it does not have the exciting ‘happy’ ending that Davies and Co all wanted: Rebekah Brooks, the former NotW and Sun editor whom they saw as the voice of Rupert Murdoch on Earth, has been, Hack Attack grudgingly concludes, ‘acquitted on all charges by the jury’. It seems Davies could not bring himself to write ‘not guilty’. Never mind. Davies and Rusbridger can look forward to learning who will play them in the fairytale film version of Hack Attack. They will have to go some way to top the casting for The Fifth Estate, the movie about the Wikileaks affair, where the Guardian pair were portrayed by David Thewlis and Peter Capaldi respectively. For some reason that brings to mind Capaldi’s pre-Dr Who role, as New Labour media maestro Malcolm Tucker, acidly describing the Guardian as ‘the newspaper that hates newspapers’.

Maybe Gorgeous George could call on his sources to help sex the story up a bit. Davies describes how, in the midst of the hacking investigation, Rusbridger told him it felt as if they were ‘living in a Stieg Larsson novel, full of endless plots and dark machinations’. Coincidentally, the real hero of those Larsson novels and movies is not, of course, the girl with the dragon tattoo who kicked the hornets’ nest. It is Mikael Blomkvist, the middle-aged investigative journalist/editor who saves both her and the day from the forces of darkness. While wearing a leather jacket.

Mick Hume is spiked’s editor-at-large. His book, There is No Such Thing as a Free Press… And We Need One More Than Ever, is published by Societas. (Order this book from Amazon(UK).) Visit his website here.

Hack Attack: How the truth caught up with Rupert Murdoch, by Nick Davies is published by Chatto & Windus. (Buy this book from Amazon(UK).)

You’ve read 3 free articles this month.

Support spiked and get unlimited access.

Help us hit our 1% target

spiked is funded by readers like you. It’s your generosity that keeps us fearless and independent.

Only 0.1% of our regular readers currently support spiked. If just 1% gave, we could grow our team – and step up the fight for free speech and democracy right when it matters most.

Join today from £5/month (£50/year) and get unlimited, ad-free access, bonus content, exclusive events and more – all while helping to keep spiked saying the unsayable.

Monthly support makes the biggest difference. Thank you.

Comments

Want to join the conversation?

Only spiked supporters and patrons, who donate regularly to us, can comment on our articles.