Germany’s unfunny attack on the freedom to mock

Don't blame Turkey for Germany's prosecution of a satirist.

Want unlimited, ad-free access? Become a spiked supporter.

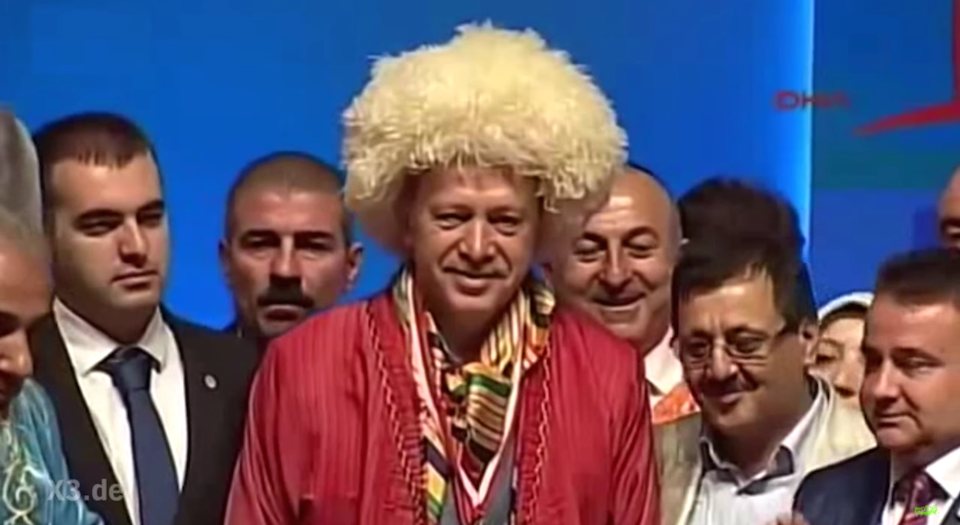

‘According to our standards in dealing with satire, the fury of Turkish president Recep Tayyip Erdogan seems surprising’, wrote publisher and graphic designer Klaus Staeck in the Berliner Zeitung last week. He was referring to a two-minute satirical video about Erdogan, broadcast by the German comedy show extra3 a few weeks ago, which prompted the Turkish government to summon the German ambassador to Turkey and demand the removal of the video from the internet.

Criticism of Turkey soon followed. German foreign minister Frank Walter Steinmeier said he expected Turkey to uphold the principles of free speech, and European Commission chief Jean-Claude Juncker said that Turkey had further distanced itself from the EU. Andreas Lange, extra3’s producer, said the Turkish state’s reaction merely confirmed extra3’s importance. ‘We don’t do this just to be funny’, Lange said. ‘We do it because these are things that we believe need to be addressed.’

Then came the second incident, but this time it was the German state trampling all over free speech, albeit with Turkey’s encouragement. Incredibly, one of Germany’s most popular satirists, Jan Böhmermann, is facing prison after he read out a poem mocking Erdogan on the public channel ZDF. Berlin newspaper Tagesspiegel reported the assessment of the German foreign ministry: ‘It is highly likely that [Böhmermann] has committed a crime.’

Böhmermann read the poem on his show, Neo Magazin Royale, on 31 March. He sat in front of a Turkish flag, beside a small portrait of Erdogan, and announced that what he was about to read was ‘slander’. And he was right. In the poem, he referred to Erdogan as, among other things, a man whose ‘body matter smelled so bad that it was worse than a pig’s fart’. Other lines included, ‘What he loves is fucking goats / while stomping on minority votes’; ‘At night, instead of sleep, he has oral sex with sheep’; and ‘Erdogan is not just thick, he’s a man with a very small dick’. Turkish subtitles were included.

It’s absurd, obscene stuff. And it is odd that the Turkish president has become a favoured target for German satirists, who seem strangely unable to find objects of ridicule closer to home. Still, this time, at least, the satire has put Germany’s government, and not Turkey’s, on the spot.

Perhaps this was Böhmermann’s intention. He said that while extra3’s short was protected under Germany’s freedom-of-press laws, his slanderous poem wasn’t. In other words, he wasn’t exposing the limits to free speech in Turkey, which are now common knowledge; he was exposing the limits to free speech in Germany, which too few acknowledge.

Böhmermann’s poem falls foul of paragraph 103 of the German criminal code, which reads: ‘Whosoever insults a foreign head of state or an accredited diplomat in Germany… shall be liable to imprisonment of up to three years or a fine. A slanderous (calumnious) insult could be punished with up to five years.’ So it was no surprise when Gerd Deutschler, a Mainz-based prosecutor, told reporters last week that Böhmermann was being investigated.

So why is the German state actively kowtowing to the interests of a foreign state? Partially it’s because it wants to maintain friendly relations with Turkey, especially as the migrant crisis rumbles on. Moreover, diplomacy and managing inter-state relations constitute one of the main reasons for the existence of paragraph 103. Postwar Germany has always tried to avoid diplomatic conflict, which is why it inserted this clause into its criminal code. It was a way of controlling debates in Germany so as not to upset foreign powers, which meant, for example, that Kurds living in Germany couldn’t criticise the Turkish president. The last time paragraph 103 led to a furore was in 1967 when the Shah of Iran felt insulted by German student protests, which prompted the then interior minister Paul Lücke to head to Iran in order to appease the Shah.

This time, the German political establishment was quick to censor Böhmermann. As soon as news of the poem began to spread, ZDF deleted the video from its website and combed YouTube for copied footage (although it has since been put back up on the Bild website here). And, while ZDF busied itself with the removal of Böhmermann’s poem, chancellor Angela Merkel personally intervened with a phone call to the Turkish prime minister, Ahmet Davutoglu, in which she called the poem a deliberate insult.

There are of course plenty of other laws and regulations that restrict free speech in Germany, some of them worse than paragraph 103, from libel laws to laws against Holocaust denial. There have also been many examples of politicians exerting informal influence over broadcasters and the press to silence certain voices: for example, political pressure has been put on newsmakers not to give a platform to newly founded protest party Alternative für Deutschland.

Yet where many German politicians and pundits have been eager to condemn attacks on free speech in Turkey, they have been silent about many of the attacks on free speech at home.

The German state clearly didn’t like the Böhmermann poem. Whereas the extra3 skit served a purpose by helping to make Germany look more democratic and free than Turkey, the Böhmermann poem was too much – too snotty, too rude, too insulting. That’s why Merkel went out of her way to say the poem was nothing but an objectionable, slanderous text. She’s been backed by the German cultural establishment, too. Markus Kompa, an expert in copyright and media law, reportedly said: ‘Unlimited freedom of opinion isn’t necessarily a cultural gain. Limits have to exist, people don’t have to put up with everything.’

Indeed, since the poem controversy began, many have been debating the limits to satire. Yet the very posing of the question of satire’s limits is problematic. As Kurt Tucholsky put it in 1919, there should never be any limits to satire. Moreover, the extent to which satire offends those in authority is often a mark of its success. Hence the famous German author and satirist, Frank Wedekind (1864-1918), editor of one of Germany’s most famous satirical magazines, Simplicissimus, was sentenced to several years in prison after publishing a hilarious and disrespectful poem addressed to ‘His Majesty Kaiser Wilhelm II’. What Wedekind understood better than today’s satirists, with their sights trained on Erdogan, is that criticism ought to be directed against one’s own government, not another’s. As the old left dictum runs, the enemy is at home, not abroad.

Unlike Wedekind, of course, we are not fighting a repressive state apparatus. However, the Böhmermann case does make one think. Not only must we scrap paragraph 103, we should also abolish the many other clauses that limit free speech and press freedom in Germany (especially paragraph 90, which outlaws any slander against the German president). After all, Erdogan is not the only thin-skinned politician around. In 2006, the then leader of the Social Democrats, Kurt Beck, sued the German satirical magazine Titanic after it featured him on its front cover with the headline: ‘Problematic bear, completely out of control’ (an allusion to a real bear, dubbed ‘the problem bear’, which had then been recently hunted in Bavaria after killing several sheep).

But today, the problem is not just state censorship; there is also informal censorship. There have been far too many examples of self-appointed paragons of virtue saying ‘You can’t say that!’ when someone is perceived to have overstepped the boundary of acceptable speech. This certainly happened to Böhmermann. And, as we have seen, the German government needs no encouragement when it comes to censoring disrespectful or shocking talk.

The news over the weekend that the Turkish government would be demanding that Germany prosecute Böhmermann was hardly a surprise. But even though most commentators are blaming Turkey for Böhmermann’s plight, make no mistake: his censorship is a problem created in Germany itself.

Sabine Beppler-Spahl is head of the board of the liberal thinktank Freiblickinstitut e.V., which has published the Freedom Manifesto. She is also the organiser of the Berlin Salons.

Picture by: extra3.

£1 a month for 3 months

You’ve hit your monthly free article limit.

Support spiked and get unlimited access.

Support spiked – £1 a month for 3 months

spiked is funded by readers like you. Only 0.1% of regular readers currently support us. If just 1% did, we could grow our team and step up the fight for free speech and democracy.

Become a spiked supporter and enjoy unlimited, ad-free access, bonus content and exclusive events – while helping to keep independent journalism alive.

———————————————————————————————————————————–

Exclusive January offer: join today for £1 a month for 3 months. Then £5 a month, cancel anytime.

———————————————————————————————————————————–

Monthly support makes the biggest difference. Thank you.

Comments

Want to join the conversation?

Only spiked supporters and patrons, who donate regularly to us, can comment on our articles.