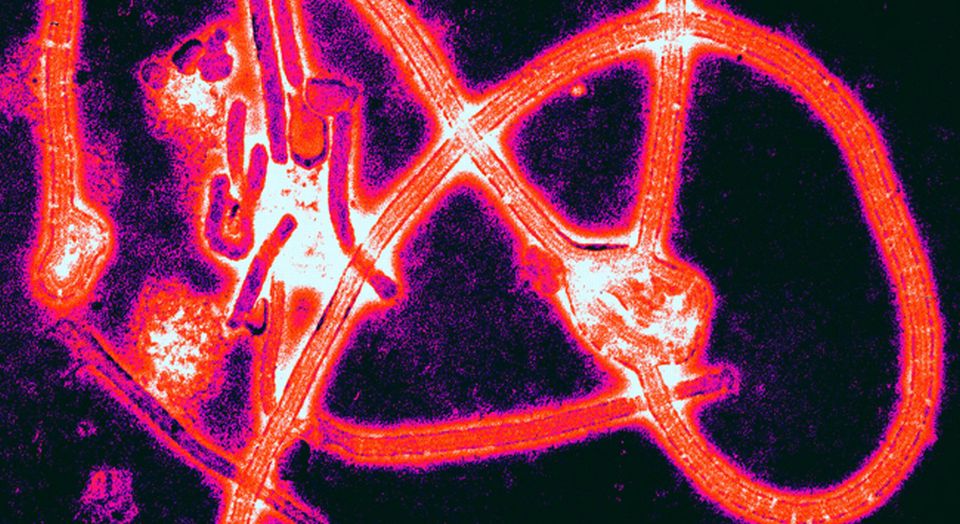

Ebola: the culture of fear goes viral

The real threat to the West does not come from ebola.

Want unlimited, ad-free access? Become a spiked supporter.

Ebola is a serious problem – for those living in the West African states of Liberia, Sierra Leone and Guinea, that is. Massive underdevelopment and the attendant problems of inadequate infrastructure and political dysfunction have created a situation in which a virus like ebola can flourish. Living conditions are sometimes cramped and unclean, water supplies are limited, medical treatment is scarce, and officialdom, such as it is, is mistrusted. It means that since February/March, the current ebola outbreak has managed to infect approximately 10,000 people, of whom nearly 5,000 have died. So it is serious – as serious, in fact, as tuberculosis and malaria, which also kill thousands of people in parts of Africa every year.

What ebola is not, though, is a problem for the developed world. And nor is it ever likely to be. That’s not just because ebola has a low transmission rate (of about one new case for every individual infected). It’s not just that to catch it you have to be exposed to the bodily fluids (blood, vomit or fecal matter) of a sufferer during the latter stages of the infection. It’s not just that it is not airborne, and therefore requires actual physical contact with a sufferer to be contracted. No, the reason why ebola will not be able to have the same impact in the West that it is having in West Africa is simple: development. The clean, running water; the sewage systems; the hi-tech healthcare; the efficient public services; the medical expertise… all these aspects of social and economic development mean that an epidemic of a virus like ebola in the West, like epidemics of those less voguish illnesses such as malaria and tuberculosis, is near enough unimaginable.

Or at least it ought to be. Yet for too many in positions of power in the West, an ebola epidemic is now all too imaginable. It’s a worst-case scenario become a very real possibility, a movie-like spectre become a real-life menace. Just listen to UK prime minister David Cameron call ebola ‘a very serious threat to the UK’, a call which resulted in the fear-spreading PR exercise of screening people for infection at UK airports. Just listen to US president Barack Obama describe ebola as ‘spiralling out of control’, a statement which came amid the quarantining of ever-growing numbers of US citizens suspected of coming into contact with an ebola sufferer. Or just listen to the soothing tones of the World Health Organisation (WHO), which helpfully described ebola as ‘a potential threat of an unparalleled human catastrophe’. Politicians and officials are falling over themselves to warn us of the threat of ebola, even as they tell us not to be worried.

And this official response, full of fear and foreboding, makes things far worse. Not only does it disrupt people’s everyday lives, it reinforces a widespread sense of existential insecurity, a feeling that the world, the future, is a risk to be managed, a threat to be tackled. The end of life as we know it seems always to be on the horizon. What’s more, in the shape of the much-prophesied global pandemic, this fear of the future, this hyper-consciousness of the worst-case scenario, morphs into a fear of others – their touch, their proximity, especially, in this case, if they’re from the dark continent.

Yet at the same time, as officialdom has often appeared panicked, and politicians have struck enthusiastically fearful poses, there has also been a great deal of criticism of the response. Many commentators have pointed out that ebola is not really a threat to the West. Many have noted that politicians seem to be indulging the politics of fear. And many have drawn attention to the corrosive effects of encouraging people to be fearful of others, especially if they’re from West Africa. As the Guardian’s Sarah Boseley observed: ‘Ebola panic is rife. Makeup artists at the BBC are said to be worried about touching the faces of interviewees from Guinea, a school cancelled the visit of a mother and child from Sierra Leone, and rumours and conspiracy theories float through the air in a way that the ebola virus cannot.’

But there’s something that rings a little hollow in the widespread debunking of ebola’s threat to the West. Because while many are rightly excoriating the authorities for their hamfisted, terror-inducing response to ebola, all too often these self-same uber-rationalists embrace and exonerate other manifestations of today’s culture of fear. Some will wonder at the prospect of large-scale terrorist attacks. Others will talk darkly of an obesity timebomb. And many will chirrup on and on about the environmental disaster apparently unfolding in our midst. So, in the same publications in which critics correctly lay waste to the ebola panic, you will frequently find arguments endorsing US navy chief Samuel Locklear’s pronouncement that ‘climate change is our single greatest security threat’; you’ll often come across pieces asserting that climate change is about to create an unprecedented ‘humanitarian crisis’; and you’ll do well to avoid pieces urging us to change our heartily consumerist ways or else face a hot-and-sweaty end of days.

Too many of those criticising the ebola panic are unable to see it for what it really is. They view it as a species of irrationalism, a deviation from scientific reasonableness. Hence much of the criticism of the panic often goes hand in hand with calls for a new, trusted scientific authority to be in charge of sorting the panics from the threats, of deciding whether this or that illness is worthy of worry. But the ebola panic is not simply irrational. It’s not just a case of misinformation. Rather, like climate change itself, the ebola panic is the product of a broader social and cultural narrative in which the future appears as an ever-proliferating series of threats, a malaise in which the social and technological gains of modernity have themselves been called into question – it’s no coincidence that for both climate-change alarmists and ebola panickers, air travel is seen as a problem.

So, yes, we should criticise the ebola panic. But we should also criticise those other manifestations of the culture of fear for the debilitating and miserable fantasies that they are.

Tim Black is deputy editor at spiked.

Picture by: Wikimedia Commons

£1 a month for 3 months

You’ve hit your monthly free article limit.

Support spiked and get unlimited access.

Support spiked – £1 a month for 3 months

spiked is funded by readers like you. Only 0.1% of regular readers currently support us. If just 1% did, we could grow our team and step up the fight for free speech and democracy.

Become a spiked supporter and enjoy unlimited, ad-free access, bonus content and exclusive events – while helping to keep independent journalism alive.

———————————————————————————————————————————–

Exclusive January offer: join today for £1 a month for 3 months. Then £5 a month, cancel anytime.

———————————————————————————————————————————–

Monthly support makes the biggest difference. Thank you.

Comments

Want to join the conversation?

Only spiked supporters and patrons, who donate regularly to us, can comment on our articles.