Dorothea Lange can speak for herself

Curators need to stop crowbarring their politics into retrospectives.

Want unlimited, ad-free access? Become a spiked supporter.

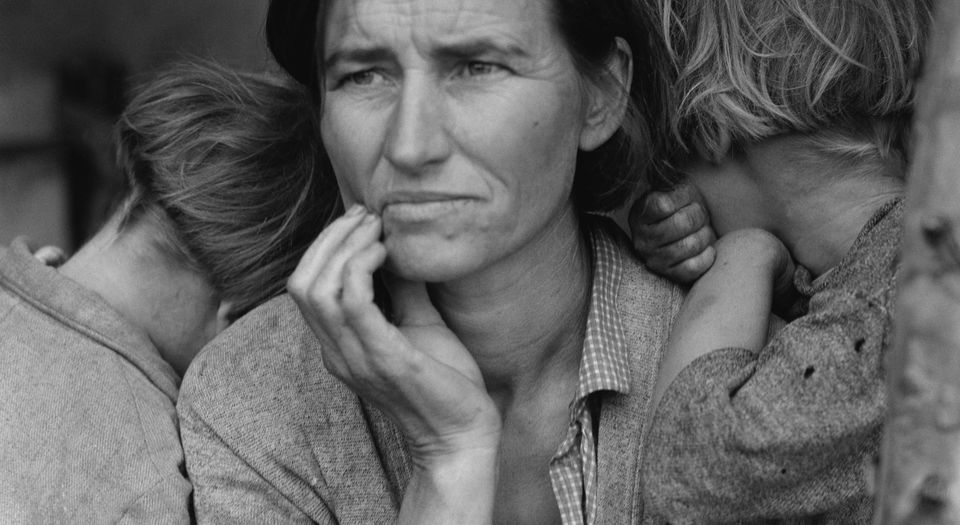

Dorothea Lange (1895-1965) was one of America’s foremost photographers. She made her name as a chronicler of the 1930s Great Depression in America’s Midwest. Her portrait of Florence Owens Thompson, also known as ‘Migrant Mother’, has become a symbol of both Lange’s striking talent and the human cost of the Depression. Lange was a prolific photographer until she succumbed to a long illness in the mid-1950s. A new exhibition at the Barbican, Dorothea Lange: Politics of Seeing, provides an exhaustive, chronological overview of her work.

There are 15 collections of works on display, and the curators deserve praise for a thorough exhibition. They range from Lange’s early studio portraits in 1920s San Francisco to the sweeping images of Ireland and its people that she took towards the end of her career. Her early portraits of local friends and artists are as small and insular as the parochial subject matter. Here, Lange is an emerging talent, with little to suggest an era-defining artist in the making.

All of that changed when economic migrants appeared in San Francisco in the 1930s looking for work. The arrival of hundreds of thousands of people from the Dust Bowl states of Oklahoma, Kansas and Texas became a defining political and artistic moment. Lange’s portraits draw out their subjects’ subtle expressions, shadows and grimaces, counterposing them to the impersonal political forces shaping their lives. She also made great use of America’s imposing landscape, capturing its wide horizons and baking sunshine, which accentuate the squalor of the displaced migrants. But her photos were not engaged in crass point-scoring about the ‘dark side of the American dream’. She captured the agency of the unemployed, their hope and aspiration for a better life that remained frustratingly out of reach.

Less well known is her series ‘Japanese American Internment’. Smaller in number than those chronicling the Great Depression, these photographs document the fate of the 120,000 US citizens of Japanese ancestry who were rounded up and relocated to makeshift prison camps for the duration of the Second World War. Lange was hired by the War Relocation Authority to document the camps. But the authorities were uncomfortable with the photographs she produced, and they remained hidden for decades. There is nothing sensationalist or exploitative about them: one set of photographs even shows a pair of young Japanese men laughing and smiling for the camera. But, as Lange put it, photography is a ‘peculiar and powerful instrument for saying to the world: this is how it is’. Confronted with these matter-of-fact images of internment, it’s little wonder the authorities chose to shelve them.

The final part of the exhibition focuses on Lange’s interest in the impact of huge construction projects, such as a dam and large reservoir built in Solano County, on the environment and local communities. In 1953, these photos, published in Life magazine, were seen as overly romantic and backward looking – at the time, such projects were the essence of progress. Equally jarring is a set of photos that reflect the relative prosperity of the postwar period, including relatively affluent suburbs and shopfronts. The images appear neutral and detached, but they are presented as stinging critiques of ‘consumerism’ and American notions of ‘progress’. It does feel a little tenuous.

No doubt Lange was becoming more nostalgic for a simpler life in her later years – this is reflected in her series on Irish peasants. But it seems the curators of this exhibition are particularly eager to ram home a message about the perils of progress. In the educational packs related to this exhibition, there are activities asking students to question whether human progress is worthwhile. For decades, progress wasn’t a word to place in inverted commas, to mock its meaning or its worth. It’s a sign of the times that Lange’s photographs of relative prosperity are seen as just as damning as her portraits of grinding poverty.

Neil Davenport is a writer based in London.

Dorothea Lange: Politics of Seeing is at the Barbican in London until 2 September.

Picture by: Getty

£1 a month for 3 months

You’ve hit your monthly free article limit.

Support spiked and get unlimited access.

Support spiked – £1 a month for 3 months

spiked is funded by readers like you. Only 0.1% of regular readers currently support us. If just 1% did, we could grow our team and step up the fight for free speech and democracy.

Become a spiked supporter and enjoy unlimited, ad-free access, bonus content and exclusive events – while helping to keep independent journalism alive.

———————————————————————————————————————————–

Exclusive January offer: join today for £1 a month for 3 months. Then £5 a month, cancel anytime.

———————————————————————————————————————————–

Monthly support makes the biggest difference. Thank you.

Comments

Want to join the conversation?

Only spiked supporters and patrons, who donate regularly to us, can comment on our articles.